Part 6: Electrical equipment summing up

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

UNRELIABLE electrical equipment is a major problem for heavy-vehicle operators and since reliability is being sold as the main advantage of a premium specification vehicle any way of improving electrical reliability should be considered.

American practice is to use 12V electrical systems on heavy vehicles, spares and repairs being more readily available from garages or auto electrical specialists who are equipped to work on 12V systems but not 24V.

Most electrical equipment for a heavy vehicle would be heavy-duty equipment, whether it was 12V or 24V. so such repairs may only be temporary but if, for example. an alternator or windscreen wiper motor stopped working about 200 miles from base on a wet evening it could be a case of a repair using a 12V car spare or no repair at all and a long delay. Such items as 12V bulbs are easier to obtain than 24V.

Other advantages of a 12V system include the availability of more sophisticated equipment initially developed for cars. Sealed-beam quartz-halogen headlamps are an example. In some cases the same item is cheaper in 12V than in 24 because production volume of the 12V item is greater. And 12V lamp filaments are more robust than 24V so the lamps last longer. A heavier duty wiring harness is necessary for 12V so broken connections should be less frequent, but the difference is not significant as bad routeing is the main cause of broken connections.

The disadvantages of 12V electrics on a heavy vehicle are in the starter circuit. A 12V starter requires twice as much current as a comparable 24V, which means double the size conductors, double the number of brushes and double the length of commutator, resulting in a bigger and more expensive starter motor.

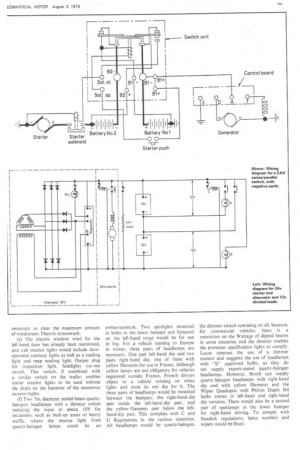

Voltage drop in a 12V starter circuit must be kept to less than half the drop acceptable in a 24V circuit and, because of the sensitivity of 12V systems to voltage drops. higher capacity-batteries are required. Cummins recommends twice the capacity, for the 14-litre engines. At 0 deg C, 24V requires 150 ampere-hours and 12V requires 300 ALL and at —18 deg C. 24V requires 200 Ah and 12V requires 400 4h. The cost and weight of the extra 200 ampere-hours (82kg and about £70 recommended retail for two Lucas AC 175 batteries) is considerable so a mixed voltage electrical system is the answer for the premium specification tractive unit, with a 24V starter and the rest of the equipment I2V. Four heavy-duty 6V batteries are used, connected in series! parallel for charging and lighting and in series for starting by means of a series / parallel switch or change-over relay.

An alternative arrangement is to connect the batteries in series for, both charging and starting. and to divide the electrical load of the vehicle into two equal parts, each connected to one of the batteries. This has the advantage that a series /parallel switch is not necessary and a 24V trailer output is easy to arrange, but as well as the alternator other electrical circuits which cannot be split equally have to be 24V. So, as a mixture of 12V and 24V equipment on a vehicle is an untidy arrangement, the series /parallel switch is preferred.

For UK use, Lucas /CAV equipment would be used, but overseas, particularly in Central Europe, service is better for Bosch, so Bosch equipment should be considered. Bosch can supply suitable 24V starters. change-over relays and a vast range of 12V equipment, but the starters are not approved alternatives for the RollsRoyce or Cummins engines. The other alternative make is AC Delco with worldwide service through General Motors outlets. AC Delco 24V electrics are standard on the British-made Cummins engines, and AC Delco could supply 12V starters if required. On Detroit Diesel engines 12V equipment is standard, 24V costing about £40 extra.

Thus electrical equipment on the premium specification tractive unit comprises: (a) 24V positive engagement starter. CAV model SI3OL or equivalent.

(b) I2V, 720 Watt alternator, C AV model AC5R or equivalent. The AC5R has a built in regulator and is a heavy-duty alternator with a design life of 250,000 miles.

(c) Four heavy-duty 6V batteries Lucas AC 175 or equivalent minimum 200 Ah and series /parallel switch. The engine coldstart equipment and possible use of electricpowered engine cooling fan or fans has been covered in the engine article.

(d) Dual intensity on indicator and stop lights to reduce after-dark dazzle from them. Flasher unit placed in the cab where the driver can hear it click so there is no possibility of it being left on after a corner. The latter may seem a minor point but it could save a major road crash and the flasher unit on early Bedford TKs was so placed. Hazard warning, and a stoplights "on" switch enabling the trailer stop lights to be used as rear fog lamps. Windscreen wipers with two-speed and intermittent action, about 60, 30 and 10 sweeps per minute. The wipers would be three-blade or pantograph-action if necessary to clear the maximum amount of windscreen. Electric screenwash.

(e) The electric window wind for the left hand door has already been mentioned, and cab interior lights would include dooroperated courtesy lights as well as a reading light and map reading light. Output plug for inspection light. Sidelights cut-out switch. This switch, if combined with a similar switch on the trailer, enables trailer interior lights to be used without the drain on the batteries of the numerous exterior lights.

(I) Two 7in.-diameter sealed-beam quartzhalogen headlamps with a dimmer switch reducing the input to about 10V for occasions, such as built-up areas or heavy traffic. where the intense light from quartz-halogen lamps could be an embarrassment. Two spotlights mounted in holes in the lower bumper and focussed on the left-hand verge would be for use in flog. For a vehicle running to Europe in winter, three pairs of headlamps are necessary. One pair left-hand dip and two pairs right-hand dip. one of these with yellow filaments for use in France. Although yellow lamps are not obligatory for vehicles registered outside France. French drivers object to a vehicle running on white lights and most do not dip for it. The three pairs of headlamps would be mounted between the bumpers. the right-hand-dip pair inside the left-hand-dip pair, and the yellowfilaments pair below the lefthand-dip pair. This complies with C and U Regulations in the various countries. All headlamps would be quartz-halogen.

the dimmer switch operating on all, because, for commercial vehicles, there is a restriction on the Wattage of dipped beams in some countries and the dimmer enables the premium specification lights to comply. Lucas opposes the use of a dimmer resistor and suggests the use of headlamps with "Eapproved bulbs. as they do not supply export-sealed quartz-halogen headlamps. However. Bosch can supply quartz-halogen headlamps with right-hand dip and with yellow filaments and the Wipac Quadoptic with Philips Duplo 1-14 bulbs comes in left-hand and right-hand dip versions. There would also be a second pair of spotlamps in the lower bumper for right-hand driving. To comply with Swedish regulations, lamp washers and wipers would be fitted.

(R) Other lights are side and rear lights with 9W SBC buoy marker bulbs and rear end indicators in "5 in 1" fittings. Parking lights on each side and top markers on the cab roof both with 4W IVIBC bulbs. Dimmer on instrument panel lights and reversing light on the back of the cab for picking up trailers after dark. All electrical equipment including windscreen wipers and heater blowers would be suppressed for radio interference, and negative earth would be used.

There is no way of guaranteeing absolute electrical reliability, but use of the best available electrical equipment coupled with particular attention to the siting of junction boxes and routeing of cables should reduce electrical problems to an acceptable level.

Conclusions

The specification described in preceding sections is that of an up to date 32-ton tractive unit intended to give the transport operator maximum productivity, while causing minimum environmental nuisance. It is entirely practicable being assembled from . parts already either in production or in the final stages of development. There are no advanced features like, for example, selfadjusting brakes as, with a retarder, these

are not necessary, and possible future developments such as head up instrument displays, or donkey engines to power vehicle systems, have not been considered.

Like all specifications it is a compromise, being weighted in favour of economy, as a true premium specification would have the NTA 400 engine, automatic transmission (both completely cocooned for silencing) anti-skid brakes on both axles, air suspension and so on, but such a specification is far in advance of any legislation proposed for the foreseeable future, and a company running a true premium specification unit at present would have to set higher operating costs against prestige value. But even the compromise specification is equal to, if not better than, the best Continental models.

In terms of power the 340/350 bhp engines compare favourably with leading French and Swedish models, and the 400 bhp engine is better than the most powerful Dutch and German tractors. These high-powered vehicles are intended for operation at up to 40 tonnes at a minimum power/weight ratio of 8 bhp/tonne (DIN). And, apart from meeting possible future regulations, the high power/weight ratio is the most important advantage of the premium specification to the vehicle owner as it results in better long

term reliability. in creased safety, low maintenance costs and long service life, all adding up to more profit. It does not necessarily lead to increased fuel consumption, as a high power/weight ratio enables the vehicle to have a very high top gear for economical motorway running, combined with adequate hill-climbing ability using standard heavy-duty transmissions. High power-to-weight for high productivity is also a sensible move in view of the shorter driving hours due to take effect here under EEC rules from January 11976: any operator buying underpowered vehicles now would be very shortsighted.

In today's political/environmental atmosphere the environmental advantages of premium vehicles should be emphasized. Low noise level is particularly important, as apparent size is proportional to the noise emitted. Braking efficiency of 70 per cent on a good surface is also important, as a safety factor.

So far I have made no reference to cost. The likely price of a premium specification tractive unit is difficult to estimate because o.e. prices for components are disclosed only to vehicle makers — and makers' profit margins are not known. But if one takes a typical 32-ton two-axle tractive unit with Rolls-Royce Eagle 220 or Cummins NHK 220 engine and adds likely costs for specifying an Eagle 340 or NTC 350 engine, large radiator and thermostat-controlled fan, torque converter, Maxaret on rear axle, Telma retarder, automatic lubrication, Transcontinental cab and extensive. silencing, the total sales price is unlikely to be less than £10,000. It could perhaps be

less if a multi-speed manual gearbox were used instead of the torque converter; but it could be considerably more if, for example, a safety conscious operator insisted on lvlaxaret on both axles.

Using the NTA 400 engine and appropriate transmission would cost at least £500 more and a version eauipped for international work with extra heaters, lights and engine cold start, possibly air suspension and sanding boxes could cost another £500 to £1000 — and considerably more if the full spec for temperatures down to —40 deg C were fitted. Thus the price of a fully eauipped TIR tractive unit is very high, and the price of a UK premium specification unit could be between £9500 and £10.500. Compared with a tractive unit costing perhaps £7500 this is, say, £4 to 16 a week extra over 10 vars. It does not need an accountant to see that its extra earning potential is many times this figure.

Unladen weight is easier to estimate — probably 6500kg, depending on the extent of acoustic cladding and the type of transmission.

Who'll build it?

Having put the case for a premium specification tractive unit and shown how a suitable vehicle could be assembled at a realistic price from available components, it is appropriate to ask why such a vehicle is not already on the market. This can best he done by giving a brief resume of the results of approaches to possible manufacturers. In 1970 an inquiry was made of AEC, suggesting that the Mandator V8 could be the basis of a suitable TIR tractive unit. The reply stated that "... the V8 Mandator is the finest machine produced for TIR operation in the world" and went on to say how it could run rings round any Volvo or Scania.

In 1972 proposals were put to Atkinson, ERF. Fodens and Scamtnell, suggesting that their existing 32-ton two-axle Cummins or Rolls-engined units could be the basis of a tractive unit comparable with leading Continental models. In the case of Atkinson and ERF an offer to meet half the cost of a prototype. estimated at about £15,000, was included.

Atkinson turned the proposal down, saying the Atkinson/Seddon development programme was fully committed for five years. ERE, after discussion, offered to consider it provided an initial order for 50 units in 12 months was forthcoming. Fodens acknowledged the proposal and promised that a decision would follow. Scammell apparently assumed the proposal was an inquiry for a production model Crusader and passed it to a Scatninell dealer.

Early in 1973 the above four companies, together with Argyle, Dennis and RollsRoyce were asked if they would consider making a premium tractive unit provided sufficient orders were forthcoming.

Argyle said it would take two years to develop, and that development costs plus the lack of volume production of lower-spec vehicles to help spread the overheads would make the price high. Dennis said group policy was to make only environmental control vehicles. Atkinson did not reply.

ERF agreed with the concept but said initial price was important, especially in the UK, and felt that its European tractive unit (now known as the NGC 360 or 420) represented the best specification that could be sold at a competitive price. I regard this model as the nearest approach to a premium specification by a British manufacturer, but it lacks such items as automatic chassis lubrication, a brake system incorporating a retarder, an anti-jack-knife device, extra silencing and a thermostat-controlled fan. Definite non-premium features are a gearing which gives 57 mph flat out, and alternative engines giving less than 6 bhp/tonne at 42 tonnes.

Fodens eventually said ". . . as we are already producing what is generally known as a premium specification tractor unit, that is our new S.80 model, there is little we can do ...".

Rolls-Royce Motors Diesel Division, which used to make Sentinel lorries. confirmed that its policy was to avoid competing with their customers and to concentrate on producing engines to meet the needs of all producers of heavy trucks.

Scarnmell, however, said it was prepared to manufacture a premium specification unit if it received sufficient orders to make it a financially viable proposition. It would be based on an Eagle 340-engined Crusader, and Scarnmell also pointed out that the present Crusader 280 would evolve towards a premium specification in the course of time, as operators gradually realized the advantages of better vehicles. An example of this is that once the first Crusader 280 is added to a fleet, no more Crusader 220s are bought by that operator. The Crusader 220 is offered as a stepping stone to an adequate power/ weight ratio for the benefit of operators steeped in a long tradition of 32-tonners with 150 or 180 bhp. engines.

The market for a premium specification tractive unit exists. UK operators travelling overseas almost all use big Scanias or Volvos in the maximum-weight class, but more obvious proof is the number of these models seen in regular use in Britain, Although the majority are on long-distance work, the reliability of a premium specification vehicle has been the main selling point in a number of cases.

The present situation seems to be that as British tariffs are adjusted to EEC levels, Dutch, French and German vehicles will begin to challenge the Swedish makes for domination of the British high quality, 32tonner market. The long-term prospects for the British manufacturers who have traditionally catered for this market are not good, ERF and Scammell possibly excepted, unless they abandon what I regard as their ostrich attitude. Pressure from operators who would like to run better British vehicles, instead of buying foreign, is the only thing likely to change this outlook.

To summarise, the premium specification vehicle has a high power/weight ratio, high gears, high brake efficiency, high initial cost and low noise level giving:— maximum driver productivity; maximum fuel economy; maximum vehicle productivity; maximum vehicle life; maximum reliability; maximum performance; maximum safety; minimum maintenance costs; minimum "juggernaut" behaviour.

Its initial cost is a small fraction ofits higher earning power. The Continentals have already learned this, and Britain should follow their lead.