CM sits in on industrial relations training

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

I HAVE recently sat in as an observer during an "in-company" training course in industrial relations arranged by Texaco Ltd.

This was of absorbing interest not merely because of its industrial relations discussions but because Texaco has been wise enough to include in its three-day courses talks about the history of the company, its operations, transport, and marketing policies.

The second day is devoted entirely to a presentation — by either Ken Jackson or Alan Law of the Transport and General Workers' Union — of the history, structure, and objectives of the union, and the responsibilities of its shop stewards. The final day is given over to Don Manser of the Industrial Society, for concentrated discussions on the implications of the Industrial,Relations Act, with particular reference to the relations of shop stewards and local management.

Why should a massive international company like Texaco, which is able to afford to pay transport drivers well, think it important that shop stewards shouldinow about their company's activities in depth? Texaco has well-qualified industrial relations officers and professional management; is it not a needless extravagance to tell shop stewards about the detailed organization of the TGWU, founded by Ernie Bevin over 50 years ago, or about the complexities of industrial relations law — on which the lawyers are far from unanimous?

One important reason is that marketing is crucial in the present phase of petroleum

production and distribution. All the massive efforts of petroleum companies to win oil from inhospitable places — consider the hazards of North Sea oil exploration and recovery, or Texaco's incredible 318-milelong pipeline across the Andes from Ecuador to the Balao terminal near Esmeraldas, on the Pacific Coast — count for nothing if petrol and oil of high quality are not available at the pumps when needed. The final commercial thrust comes from the tanker drivers.

Marketing has become a much more important sector since the OPEC oil producing countries got uppity and began to squeeze the "oil jugular" of the Western world. The major oil companies now see themselves as part of the energy market, in competition with coal, gas, electricity and nuclear power. New developments constantly threaten not only the competitive position of Texaco visa-vis their major competitors but the prosperity of the entire petroleum industry. (A large-scale introduction of district heating from power stations, such as Battersea pioneered 20 years ago on Thames-side, could displace hundreds of fuel-oil tankers.)

Two sides

Texaco's industrial relations courses include supervisors and managers as well as shop stewards. Ted Platt, the industrial relations supervisor (over 20 years in line management and two years on IR) says Texaco gave much thought as to whether shop stewards' training should be a separate activity or a joint study. The decision to make the groups mixed was, I think, wise. As Ted says, if managers are lectured separately their questions to a trade union officer would be management orientated. If shop stewards were not present they would not hear managers' questions. It helps both sides to learn of the other's point of view since neither side has a monopoly of wisdom.

Texaco uses the so-called "conference method" of training which avoids the formal lecturing approach. It is based on free discussion within a group of people with similar interests, under the guidance of a leader. The greater the variety of experience within the group the better, since each learns from the other. Naturally, it helps if all members have practical experience of the subjects under discussion though good speakers provoke interest and imagination on subjects beyond the ken of some participants.

The leader is not a lecturer claiming authority upon the subject being discussed. His job is to promote discussion and guide thinking towards desired conclusions, endeavouring . to bring everyone into the act. Case studies form part of the programme; an example: "Tom the tanker driver," devised by Ken Jackson, the TGWU's head sarang of road transport, always provides a fruitful and animated discussion.

The three-day courses keep participants hard at it from 9 am until 6 pm with an earlier finish on the final day to allow for travelling. Although the industry training board meets part of the cost, Texaco's courses are heavily subsidized by the company who provide lavish — perhaps overlavish --accommodation. Some drivers at the Darlington course I attended grumbled about the rich meals!

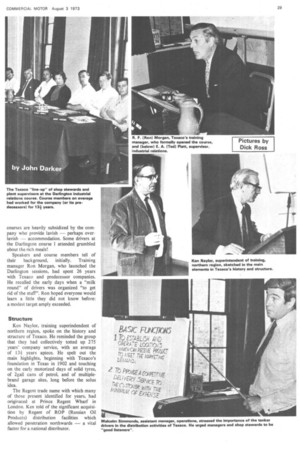

Speakers and course members tell of their background, initially. Training manager Ron Morgan, who launched the Darlington sessions, had spent 26 years with Texaco and predecessor companies. He recalled the early days when a "milk round" of drivers was organized "to get rid of the stuff". Ron hoped everyone would learn a little they did not know before: a modest target amply exceeded.

Structure Ken Naylor, training superindendent of northern region, spoke on the history and structure of Texaco. He reminded the group that they had collectively totted up 275 years' company service, with an average of 13", years apiece. He spelt out the main highlights, beginning with Texaco's foundation in Texas in 1902 and touching on the early motorized days of solid tyres, of 2gall cans of petrol, and of multiplebrand garage sites, long before the solus idea.

The Regent trade name with which many of those present identified for years, had originated at Prince Regent Wharf in London. Ken told of the significant acquisition by Regent of ROP (Russian Oil Products) distribution facilities which allowed penetration northwards — a vital factor for a national distributor. The complexities of company acquisitions, groupings, shared markets and refining strategies were touched on. The group were told of the size of Texaco; it is the third largest manufacturing corporation and the second largest oil company in the United States (and the only one able to market its fuel under its own name in every state of the Union).

Malcolm Simmonds, a chartered civil engineer, who is assistant manager, operations, soon proved he was well versed in the economics and logistics of distribution. An organization chart he displayed included the 723 truck operators (and 1500 people all told) engaged on the costly distribution job. "We're the boys who spend the money — we're bv far the biggest employment sector in Texaco's UK operations."

He stressed the importance of the tanker driver's job whether in a small or large depot. Customer service was all important in densely populated areas but equally so in remote rural areas.

Some price tags he put on routine operations and equipment were mindboggling: £285m spent on exploration and drilling in 1972: giant tankers costing .E14.4m apiece (whose price had doubled in seven years); the pipeline network owned or part-owned by Texaco, worldwide, 23.000 miles for crude and 13.000 for refined products. Of refineries he said: "If we don't find it and refine it. you chaps aren't going to deliver it."

Malcolm Simmonds (and other company spokesmen) made no attempt to talk down or over-simplify. Simmonds spoke frankly and informatively on the company's distribution strategy in the UK. The significance of Texaco's refinery at Pembroke, the use of coastal shipping and pipelines as main distribution arteries was explained.

Company planning Factors influencing new fuel storage and distribution points were discussed; closeness to the "market place"; availability of labour and land; supply costs from refinery or port; proximity to motorways, etc.

Company planning, •said Malcolm, was helped by a computer program called EDAC (Economic Distribution Area Calculator). This rapidly calculated the cost of distribution by various routes and methods. In rare cases, distribution via two alternative depots would cost virtually the same. (Later in the session drivers pitted their common sense against a computer indication of the least cost distribution method to North London petrol stations.) The simulation of a possible new location (eg a single alternative to Wisbech and Norwich) was carried out by computer. Here, it was found that distribution savings would be outweighed by additional staffing and building costs.

Texaco analyses distribution costs in great detail. The meeting learned how relative depot efficiencies are judged using such criteria as gallons delivered per man hour, gallons per drop and per trip, vehicle utilization (including fuel used) etc. The cost per vehicle mile and per gallon delivered is readily worked out.

Malcolm Simmonds ended by stressing the importance of good planning and control and sound management of people. "We all need to appreciate each other's jobs," he said. "The vast majority of management problems come from dealings with customers or employees." Managers must be good listeners and so must shop stewards. Both must be "sensible buffers", for banging the table was no answer to either side. "You're on a hiding to nothing if you think we in management are a fair load of b s just as we are if any of us assume all shop stewards are a crafty bunch of b s, always out for the maximum money for the least effort."

Truck maintenance When Vic Allen, Texaco's transport engineer, talked to the group he noted that the company (in the UK) spent £800,000 to Elm a year on new vehicles and equipment and a similar amount on tn3ck maintenance. Company policy was definable in five points:— El To build and operate safe vehicles; El Use maximum capacity trucks where possible; 1:1 Maintain vehicles to high standards and at economic cost; Develop and use modern equipment; D Standardize as far as possible on vehicles and equipment.

The general design policy, said Vic, was to keep the centre of gravity of vehicles as low as possible, if possible lower than Home Office requirements. Running gear was designed for easy "drainage". The company always fitted an anti-jack-knife device and in future would fit Maxaret as standard equipment on the majority of vehicles. Texaco, said Vic Allen, had 33 sets of Maxaret MkIII in use on Lynx vehicles before the equipment was announced to the industry. The company has made valuable suggestions to Dunlop.

In the last three years Texaco had spent over £300,000 to improve vehicle maintenance. Twenty extra fitters had been set on and the stress was on preventive maintenance. Defects were now being analysed on a computer print-out. Running costs were checked against Texaco standards and vehicles which were below par were isolated and investigated. "Standards are not easy to compile accurately", said Vic Allen. "You really need several years' accurate historical information for best results." He compared the national failure rate in vehicle tests (25-30 per cent) with Texaco's rate of 6-10 per cent, and in one recent month under 5 per cent.

Vic Allen's talk ranged widely and covered the company's experience with airoperated equipment and with particular makes of vehicles (Mandator, Big J, Atkinson, and Lynx attic — operated at 24 tons); 70 per cent of the Texaco fleet were Mandators. There were 83 Lynx vehicles operated, making Texaco the country's largest operator of this type.

Tank builders The company had undertaken a lot of research on vehicle braking and stability, and kept in close touch with tank builders because in its experience the vehicle builders did not always produce designs that were legal! The fullest use was made of suggestions from drivers and operating staff; plant committee minutes were thoroughly sifted for ideas After Vic Allen's talk some slides of road tankers taken in America by Texaco's transport manager, Don Grimster, were shown and there followed Dunlop's film illustrating the Maxaret device. Vic pointed out that a Texaco Lynx vehicle equipped with Maxaret equipment had been tested by CM. (Report in CM July 27.) There was an animated debate when the drivers were free to question Vic Allen. Detailed points of cab design, mirror placing and design. suspension gear, and particularly tyres. excited the course members. The merits (and demerits) of radial tyres (with or without power steering) were well ventilated with no holds barred!

All this solid fare was topped up by a brilliant exposition of company marketing policy by Stanley Balson, Texaco's manager — distribution development. He made no secret of the fact that the traditional "dollar a barrel" profit on oil at the wells was now a happy memory. Future profits must come in the marketing and distribution sector and he dissected the human and material elements in this.

Most of the major oil companies in Britain have invested heavily in industrial relations training in the past year or two. The excellent Texaco course may be typical of many similar courses. The effect of such intensive training on shop stewards and managers experiencing it must be valuable. Ideally, all employees should be exposed to the same process.

Personalities Very large companies need top managers with charisma — spell-binding strength of personality. To the 80,000 employees of Texaco the name of Gus Long (the 70-year-old former president) still sounds like a tocsin, for after retiring he returned to the company.

It may be that the friendly confrontations between shop stewards and managers on industrial relations courses will one day throw up powerful personalities capable of rising to the highest levels of business. Is it fanciful to imagine a tanker driver rising to the president's chair? I hope not.

Next weeks Alan Law's Texaco teach-In.