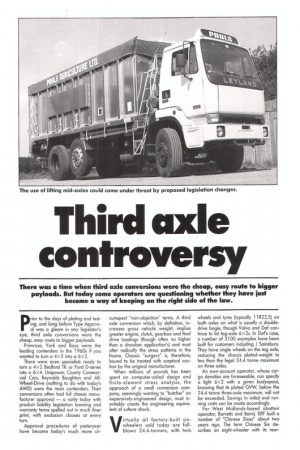

Third axle controversy There was a time when third axle

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

conversions were the cheap, easy route to bigger payloads. But today some operators are questioning whether they have just become a way of keeping on the right side of the law.

prior to the days of plating and testing, and long before Type Approval was a gleam in any legislator's eye, third axle conversions were the cheap, easy route to bigger payloads.

Primrose, York and Boys were the leading contenders in the 1960s if you wanted to turn a 4x2 into a 6x2.

There were even specialists ready to turn a 4x 2 Bedford TK or Ford D-series into a 6x4. Unipower, County Commercial Cars, Reynolds Boughton and AllWheel-Drive (nothing to do with today's AWD) were the main contenders. Their conversions often had full chassis manufacturer approval — a rarity today with product liability legislation looming and warranty terms spelled out in much finer print, with exclusion clauses at every turn.

Approval procedures of yesteryear have become today's much more cir cumspect "non-objection" terms. A third axle conversion which, by definition, increases gross vehicle weight, implies greater engine, clutch, gearbox and final drive loadings (though often no higher than a drawbar application's) and must alter radically the stress patterns in the frame. Chassis "surgery" is, therefore, bound to be treated with sceptical caution by the original manufacturer.

When millions of pounds has been spent on computer-aided design and finite-element stress analysis, the approach of a small conversion company, seemingly wanting to "butcher" an expensively-engineered design, must inevitably create the engineering equivalent of culture shock.

Virtually all factory-built sixwheelers sold today are fullblown 24.4-tonners, with twin wheels and tyres (typically 11R22.5) on both axles on what is usually a doubledrive bogie, though Volvo and Daf continue to list tag-axle 6x2s. In Daf's case, a number of 2100 examples have been built for customers including J Sainsbury. They have single wheels on the tag axle, reducing the chassis plated-weight to less than the legal 24.4 tonne maximum on three axles.

An own-account operator, whose cargo densities are foreseeable, can specify a light 6x2 with a given bodyspace, knowing that its plated GVW, below the 24.4 tonne three-axle maximum, will not be exceeded. Savings in initial and running costs can be made accordingly.

For West Midlands-based abattoir operator, Barretts and Baird, ERF built a number of "Chinese Sixes" about two years ago. The term Chinese Six describes an eight-wheeler with its rear most axle removed. Such close-coupled twin-steering axles are an attractive proposition where an operator experiences a severe diminishing load problem.

This happens when a load is removed progressively from the tail-end of the vehicle on a multi-drop delivery run, and the resulting forward weight bias can overload the front axle of a fourwheeler beyond its plated weight capacity.

However, since the allowable gross weight of a four-wheeler was increased in 1988 to 17 tonnes, many manufacturers, led by Leyland Daf, have uprated their front axles, using heavier springs and bigger wheels and tyres; 29580R22.5 covers with '152/147M' loadspeed markings are good for 7.1 tonnes in single formation. A 7.1 tonne front axle is much more tolerant of a forwardbiased centre of gravity than the 6.3 or 6.7 tonne plating limitations of 275-BOR and 150/147M marked 295-80R tyres.

This means that the need for a third axle, simply to beat front axle overloads caused by uneven weight distribution on heavy four-wheelers, has in many cases been alleviated.

In practice, the operating rationale for fitting an extra axle has not stopped at avoiding front-end overloads. The decision to go for a third-axle conversion brought the realisation that the converted 6x2 chassis would qualify for a higher plated GVW and more payload capacity.

Chris Drinkwater, marketing director of one of the UK's leading third axle conversion specialists, Southworth Engineering, says that, in theory, tiny "Ford Transit-sized" tyres on an auxiliary axle would give the extra weight capacity needed by many users. Their 2240kg axle load rating would take a basic 17tanner up to the 19 tonne GVW rating requested by many operators as a desirable maximum, above which vehicle excise duty rises by £200 a year.

Such small wheels and tyres look incongruous as, to a lesser degree, do the 285R19.5 tyres which are the smallestdiameter and lowest-rated. These are now fitted, mainly on dustcarts, by Southworth, Andover Trailers, Chassis Developments and others. The small dia meter 285R19.5 tyres are approved for a 5 tonne axle load — enough to qualify a modified 17-tonner for the 22.36 tonne operation, where the first-to-last axle dimension is less than 4.6m. The 22.36 tonne weight is another convenient "threshold", avoiding the £880 hike in VED above 23 tonnes. Drinkwater says that, in reality, the plated GVW of a converted 6x2 chassis is more often determined by Type Approval considerations than by tyre ratings or the design capacities of axles.

The DTp's "Notifiable Alterations" procedure involves, most crucially, brake system calculations designed to ensure safe, efficient retardation under all speeds and conditions. The calculations take into account vehicle performance — a function of engine power and gearing — and the vehicle's behaviour during a full pedal-pressure stop. Forward weight-transfer, as the brakes are applied, not only pitches the driver forward in his seat and the load against the headboad or its retention straps, it also imposes extra work on the front axle brakes.

Converters like Southworth are, therefore, able to "tune" the brake system of a converted six-wheeler, through careful selection of diaphragm chamber or even brake drum sizes, lever lengths and pressure valve settings, to arrive at a GVW which not only gives the customer the payload he wanted within a tolerable VED band, but also satisfies the DTp's Type Approver at that weight.

Most axles fitted as add-ons to existing four-wheelers have beams and suspensions (nowadays usually air) engineered for a loading of at least 6 tonnes. It follows, when a 17 tonne 4x2 is converted to a 6x2 grossing only, say 19 tonnes, with the third axle running on small 19.5in wheels and tyres, that the axle and suspension are considerably understressed. And the tare weight penalty is disproportionately larger.

A 19 tonne six-wheeler with a nonsteered mid axle could be expected to weigh about 750kg more than the base 17 tonne 4x2 chassis. The payload advantage is therefore a modest 1250kg.

As bigger wheels and tyres are fitted, the plated GVW goes up far more than the additional dead weight. A 22.36 tonne plated 6x2 should weigh less than a tonne more than the 17 tonne four-wheeler, implying a payload gain of well over 4 tonnes.

Where should the third axle go? There are three possibilities: up front in the Chinese Six position; immediately ahead or behind the drive axle. Each has its merits and drawbacks, depending on the 'before. and after' chassis configurations.

El by Alan Bunting