kania LBW H50 16-tonalvw four-wheeler

Page 24

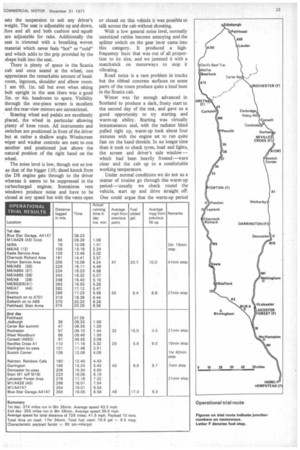

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Gibb Grace, DAuE, CEng, MIMechE

Pictures by Dick Ross UNDER the latest Construction and Use proposals the maximum permitted gross weight for a two-axle rigid remains at 16 tons (though the minimum wheelbase has been reduced to lift. Sin.) and, as a type unlikely to be outdated, the 16-ton rigid is as safe a bet as it is possible to make.

The 16-ton-gvw truck is popular on the Continent too, where it often operates with a drawbar trailer.

Scania, who have proved their competitiveness in the heavy artic classes, are hoping to increase their penetration into the UK market by way of the 164orilvw vehicle but, as I found when I tested the LB80 over CM's operational trial route recently, the smaller vehicle is relatively not as outstanding as the bigger ones.

Cab

The LB80 cab is set lower than the 110 cab and consequently the engine intrudes into the cab somewhat and only two seats are fitted. Both seats are made in Biitain by Bostrom and the driver's seat is a Viking 301 suspension type.' A lever tensioner device to the right of the seat sets the suspension to suit any driver's weight. The seat is adjustable up and down, fore and aft and both cushion and squab are adjustable for rake. Additionally the seat is trimmed with a breathing woven material which never feels "hot" or "cold" and which adds to the grip provided by the shape built into the seat.

There is plenty of space in the Scania cab and once seated at the wheel, one appreciates the remarkable amount of headroom, legroom, shoulder and elbow room. I am 6ft. lin. tall but even when sitting bolt upright in the seat there was a good 3M. or 4in. headroom to spare. Visibility through the one-piece screen is excellent and the rear-view mirrors are unrestricted.

Steering wheel and pedals are excellently placed, the wheel in particular allowing plenty of knee room. All instruments and switches are positioned in front of the driver but at rather a shallow angle. Windscreen wiper and washer controls are next to one another and positioned just above the natural position of the right hand on the wheel.

The noise level is low, though not so low as that of the bigger 110; diesel knock from the 1D8 engine gets through to the driver whereas it seems to be suppressed in the turbocharged engines. Sometimes vent windows produce noise and have to be closed at any speed but with the vents open or closed on this vehicle it was possible to talk across the cab without shouting.

With a low general noise level, normally unnoticed rattles become annoying and the splitter switch on the gear lever came into this category. It produced a highfrequency buzz that was out of all proportion to its size, and we jammed it with a matchstick on motorways to stop it vibrating.

Road noise is a rare problem in trucks but the ribbed concrete surfaces on some parts of the route produce quite a loud hum in the Scania cab.

Winter was far enough advanced in Scotland to produce a dark, frosty start to the second day of the test, and gave us a good opportunity to try starting and warm-up ability. Starting was virtually instantaneous and, with the radiator blind pulled right up, warm-up took about four minutes with the engine set to run quite fast on the hand throttle. In no longer time than it took to check tyres, load and lights, the screen and driver's side windowwhich had been heavily frosted-were clear and the cab up to a comfortable working temperature.

Under normal conditions we do not as a matter of routine go through this warm-up period-usually we check round the vehicle, start up and drive straight off. One could argue that the warm-up period uses fuel but it was surprising how much more easily the Scania climbed the early hills as a result. Both Bob, the works driver, and I—who was driving at this stage— had taken off our jackets before the start, but even so we very soon agreed the cab was too hot and turned the excellent heater down a bit.

Ride and handling

The ride, as one would expect from a long-wheelbase four-wheeler, is good; it is level and well damped. The ZF power steering is very light but nonetheless positive and, being geared for 43 turns from lock to lock, requires surprisingly little effort for the negotiation of even right-angle turns. Turns at higher speeds e.g. entering empty roundabouts or at higher speeds still, such as a slight curve, are a little worrying at first because steering effort does not noticeably increase with speed.

However the precision and responsiveness of the steering are such that one soon learns to trust it in spite of the dead feel— though I personally prefer a measure of increase in effort with speed and lock.

The steering wheel is free of all vibration and there was no noticeable bump-steer effect. A badly sunken level crossing on AS was crossed at 30 mph without a wrench on the wheel despite an audible clunk from the suspension.

Acceleration and braking The D8 provides a power-to-weight ratio of nearly 10 blip/ton and is sufficient to give the Scania an average but not outstanding performance. Comparison with other recent tests shows the LB80 to be slower away than the 16-ton Mastiff (Perkins V8) and roughly the same as the 24-ton Ford DA 2418. On the road the Scania was certainly baulked much more often than it did the baulking and there was no sense of it being underpowered.

The braking figures were taken in much worse conditions than usual but were still good by any standards. The Tapley meter that we use to take maximum deceleration readings was playing up and no peak figures were obtained but from 20 and 30 mph the average deceleration over the length of each stop was 0.47g and even from 40 mph was better than 0.4g.

All wheels locked for the tests from 20 mph but for some reason the offside front wheel did not lock from 30 and 40 mph even though the track was running with water. In dry conditions with all four wheels contributing, braking would improve considerably and be at least equal to any competitive vehicle. Spring brakes are fitted to both front and rear axles and the handbrake works through all four units, giving really effective .braking. Because of the faulty Tapley meter I was unable to check handbrake retardation but it held the vehicle facing either way on 1 in 5 gradient.

Engine, transmission and mpg The gear lever is ideally placed, the clutch effort is commendably light and the gate well defined once mastered. From the start one learns not to double declutch, as a built-in device in the box blocks any change which is attempted at too high a speed. Simple, faultless changes are made by using the synchromesh but the changes feel slow and heavy by comparison with other boxes I have used and I was not entirely happy with the LB 80's gearchange.

Gear splits are easy and 100 per cent reliable but the sliding switch did not move smoothly and unless it was right home the split could not be made. As I have said, this same switch was 'buzzing' most of the time and was obviously not quite right, but certainly the lever flick-switch seems to me much easier and more positive in use than the sliding type.

Having moved the switch the split change is made simply by depressing the clutch. A newcomer tends to declutch too quickly at first, and finds himself still in the same gear, but one soon learns to listen for the puff of air from the change cylinder, which means that the change has been made. Again this change seemed slow, especially on hills, but an adjustment allows the change time to be altered to suitindividual preference.

Ratios are generally well spaced, with the exception of 4th high and 5th low which are virtually identical.

Horsepower and torque of the D8 engine are sufficient to make the vehicle very flexible to drive. Even the very steep sections between junctions 36 and 37 and junctions 38 and 39 on M6 were taken in 5th low with typical speeds of 36 mph and 40 mph respectively. Lowest motorway speed was 27 mph, recorded just before Leicester Forest. On the two steepest climbs on the route, Riding Mill and Castleside — both approaching 1 in 5 in places — we were never below 2nd low and they were climbed in 2min 41sec and 3min 18sec respectively.

No tachometer was fitted to aid gearchange points and sometimes I hung on to a gear when, if I had known the engine speed more precisely, I might have changed and found that it pulled the next gear satisfactorily.

Fuel consumption was disappointing for a 16-ton-gvw vehicle, at 9.5 mpg overall. Fog on the Al section reduced speed and involved more low-gear work than is usual but generally average speeds were much as expected and fuel consumptions higher than expected. The Perkins V8-engined Mastiff went faster over the same route and returned 10.0 mpg and the Perkins 6.354-engined Boxer took lhr 33min longer but achieved 11.4 mpg with a bigger payload. Perhaps even more significant is that a Scania LBS80 running at 32 tons gvw returned 7.5 mpg, only 2 mpg worse than the 16-ton-gvw LB80, over the same route.

Assessing a newcomer in the strong domestic middleweight market inevitably invites comparisons — which show how very competitive some of the UK products are. For example, compared with the LB80, recently road-tested Bedford, Ford and Leyland Redline vehicles with equivalent power carried more payload and returned better average fuel consumptions at a list price around £850 cheaper; while Ford and Leyland Redline offer larger-engine options that would produce better performance and a comparable fuel consumption at prices still slightly cheaper than the Scalia. The LB80 as tested costs £4130 and the wellmade Bonallack light-alloy platform body £350.

The Scania undoubtedly scores on driver comfort — though not by as big a margin as some might imagine — and in the strength of its cab. (Eye-witnesses who saw the latest Ml pile-up commented on how well the Scanias involved had stood up compared with some others.) Whether these factors, and a reputation for reliability, are sufficient to offset the more immediate matters of fuel consumption and payload remains to be seen.