Profit from the Light-type Oiler

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A New Scheme, the Perkins Perpetuity Plan, Eliminates the Heavy Depreciation Factor and Makes Smaller Oilengined Vehicles Economical for Almost Any Operator By S.T.R.

HITHERTQ, I have always maintained that there was no practical economy to be derived from the fitting of oil engines to the lighter categories of goods chassis, i.e., those weighing under 2f tons unladen. I have always said that the extra cost of the oil engine is so large, and so disproportionate to"the cost of the chassis, that even considerable annual mileages are insufficient, in respect of the savings in fuel cost, to offset the depreciation factor in operating cost.

It is by now, I think, fairly well known that, in endeavouring to decide whether a petrol or oil-engined vehicle should be selected, the following factors must be Considered. On the credit side there is the saving in respect of fuel cost, with the oil . engine. Per contra_ there are four items of expense to be debited against this type. Two of these, namely, interest on first cost and depreciation, arise from the greatly increased amount of the initial outlay. The expenditure on lubricating oil is a little more and so is the cost of maintenance.

The Maintenance. Factor.

There is considerable controversy as regards the lastnamed item. This arises from the fact that large operators with well-organized maintenance schemes can effect maintenance of• their• oil-engined vehicles at an expense no more than, and sometimes less than, that which they find prevails in respect of petrol-enginul vehicles. The small qperator, without facilities for expert maintenance', finds the contrary to be the case. In any event, he usually discovers that expenditure on 'spare parts and replacements is so much more, in the case of' an oil engine, that his total maintenance cost -is greater than it would be with a petrol engine, even though he may save a little in respect of sundry routine maintenance-work which does not involve purchase of new parts.

Generally speaking, and having in mind, admittedly, the numerically larger body of small operators, I hold to my opinion that, with the oil engine, allowance must be made for a slightly increased cost, so far as maintenance is concerned. The position is, then, that for an oil engine to be preferable, the savings in fuel must be sufficient to exceed the extra expense on the four items named— interest, depreciation, lubricating oil and maintenance. Obviously, the annual amount of this saving is governed directly by the mileage. If the first cost of the oilengined vehicle be considerable, then it can only prove economical as compared with the petrol-engined vehicle if the annual mileage be high.

Just what this means can best be considered in relation to a popular type of lorry, weighing less than 2f tons unladen and capable of carrying a pay-load of five tons.

Operating Costs Compared.

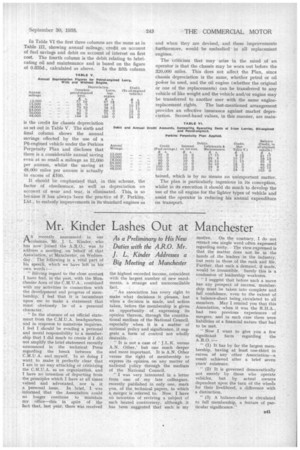

Comparative figures of operating costs are shown in the accompanying Tables I, II, and UI. All the items of operating cost are not included, but only those to which reference is made above.

Table I deals with one item only, the direct annual saving in fuel cost. It is assumed that the vehicle, when equipped with a petrol engine, covers 11 m.p.g., but that it runs 20 m.p.g. when fitted with an oil engine. The costs of the two fuels are taken to be Is. 5d. and 1s. 3d. per gallon respo:Iively, and the annual savings for various mileages are set out in the table. It should be noted that the direct siring per mile is 0.80d.

'In comparing the two types of vehicle I have assumed, as is necessary for the purpose of this article, that the operator purchases a petrol-engined vehicle and has an oil engine fitted in place of the normal unit. For reasons which will very soon become clear, I have taken as my example the Perkins P6 engine, which can be fitted to the type of vehicle I have in mind for something less than £250 (that including provision' for an allowance for the petrol engine taken out). I have taken £300 as the net initial cost of the petrol-engined vehicle, so that £550 is the corresponding figure for the same vehicle with the oil engine. • In Table II I have set out the depreciation figures for these two vehicles, for various annual mileages. In arriving at the depreciation per mile. I have not merely taken the usual figure for this type of vehicle, namely, a life of 100,000 miles ; I have, in respect of mileages less than 24,000 per annum, made additions on account of obsolescence.

For mileages of 24,000 and more, the basis of life of 100,000 miles is standardized. That explains why, in the case of the petrol engine, the depreciation per mile drops from 1.15d. for 12,000 miles to 0.72d. at 24,000 miles. The corresponding figures for the oil-engined vehicle are 2.12d. for 12,000 miles per annum and 1.32d. for 24,000 miles and upwards. In the last column of Table II the very considerable debit against the oilengined vehicle is set down.

There are still three other debit items against the oilengined Vehicle. First, there is that of interest on first cost. At 4 per cent, per annum the interest on the off-engined vehicle is £22 and that on the petrol-engined vehicle 412, a difference of 410 per annum. For lubricating oil, I have taken a figure of 0.02d. per mile additional, in respect of the oil-engined

vehicle, and for maintenance 0.10d. 12,000

15,000 18,000

per mile. These two, amounting to 24,000

30,000

0.12d. per mile, vary as regards the 48,000 total, according to the number of miles per annum.

All the foregoing are set out in detail in Table III. There is, first, the credit on account of fuel savings from Table I. Then comes interest on first cost and, after that, bracketed together, the items oil and maintenance. In the next column I have shown the balance still remaining to the credit of the oil engine. Up to that point, as can be seen, this credit is considerable, being as much as £24 per annum for 12,000 miles and rising to no less than 4126 per annum for 48,000 miles.

Next comes the debit on account of depreciation, taken from Table II, and this turns the scale in favour of the petrol engine for all mileages short of 30,000 per annum. Even at• 48,000 miles per annum, the oil-engined vehicle shows a net saving of only £.0 per annum and I should be chary of advising any operator having no experience of oil-engined vehicles to make a change with only that prospective annual saving in view.

This is a subject which I have often discussed with Mr. Frank Perkins, of F. Perkins, Ltd., well known as maker of the Perkins oil engine, also with Mr. L. W. Hancock, sales manager to that concern. The stumbling block in the way of the widespread adoption of the oil engine for the lighter type of vehicle is clearly the factor of depreciation. Were it not for the column of debit on account of depreciation, as set out in Table III, the oil-engined vehicle could be shown to be quite

B40 worth while for any annual mileage large or small.

The seemingly impossible objective of eliminating the factor of such depreciation is achieved in a new scheme, the Perkins Perpetuity Plan, which is shortly to be put into operation in respect of the Perkins P6 engine. This is, in effect, an engine-replacement scheme. In the manner of its application, however, it is quite new, for it does eliminate the extra depreciation figure from the operating cost of the vehicle to which the scheme is supplied. It goes farther ; it also extinguishes the extra one-tenth of a penny for maintenance of the engine, which I have included in the figures in Table III.

Let us assume that the purchaser proceeds on the lines indicated above-that is to say, he buys a petrolengined chassis, to which F. Perkins, Ltd., fits a P6 engine, the estia cost, with provision for allowances being, say, 4250. At each period of approximately 80,000 miles, that engine is removed and a replacement one put in for 462 10s. At the end of the third 80,000 the cost of replacement is increased to 472 10s. The engine at the end of the 320,000 miles covered by the scheme, is still capable of being replaced a.t.£72 10s.

For the purpose of this article I do not propose to go any farther than that figure of mileage. It has been demonstrated that, in the course of a period of use of 80,000 miles, no repairs of any importance are necessary. It is even lecornmended that the engine be not decarbonized in that period. It is probable, therefore, that the actual maintenance cost of this engine, apart from the £62 10s. per 80,000 miles, will be less than that of the corresponding petrol engine. I have, however, assumed that it is the same and that there is no saving in that respect.

The point to be noted is that there is no depreciation item needed in respect of the engine. The total cost over a period of 320,000 miles is as set out in Table IV. This is equivalent to 0.885d. per mile. That is fairly to be debited as extra maintenance cost and the total of extra maintenance cost and extra lubricating oil cost is thus 0.355d. per mile.

Before proceeding to deal with Table VI, which corresponds to Table III, there is one other matter to be taken into consideration. The depreciation of the chassis must be taken separately and as the chassis, less engine, can be taken as costing 4250 as against the 4300 of the original petrol-engined chassis, there is an amount to be credited to the oil engine on that accmint. The figures indicating this credit are set out in Table V, which needs no further explanation. Table VI gives the full story of debits and credits relating to a P6engined chassis, taking into consideration, in the figures, this new Perkins Perpetuity Plan.

In Table VI the first three columns are the same as in Table III, showing annual mileage, credit on account of fuel savings and debit on account of interest on first cost. The fourth column is the debit relating to lubricating oil and maintenance and is based on the figure of 0.355d., calculated as above. In the fifth column

is the credit for chassis depreciation as set out in Table V. The sixth and final column shows the annual savings effected by the use of a P6-engined vehicle under the Perkins Perpetuity Plan and discloses that there is a considerable annual saving even at so small a mileage as 12,000 per annum, whilst the saving at 48,000 miles per annum is actually in excess of 2100.

It should be emphasized that, in this scheme, the factor of obsolesence, as well as. depreciation on account of wear and tear, is eliminated. This, is so because it has always been the practice of F. Perkins, Ltd., to embody improvements in its standard engines as and when they are devised, and these improvements furthermore, would be embodied in all replacement engines.

The criticism that may arise in the mind of an operator is that the chassis may be worn out before the 320,000 miles. This does not affect the Plan, since chassis depreciation is the same, whether petrol or oil po'Wer be used, and the oil engine (whether the original or one of the replacements) can be transferred to any vehicle of like weight and the vehicle and/or engine may be transferred to another user with the same enginereplacement rights. The last-mentioned arrangement provides an effective insurance against market depreciation. Second-hand values, in this manner, are main tamed, which is by no means an unimportant matter.

The plan is particularly ingenious in its conception, whilst in its execution it should do much to develop the use of the oil engine for the lighter types of vehicle and assist the operator in reducing his annual expenditure on transport.