management

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

matters by John Darker, AMBIM Steel transport.

BSC's Shotton Works

THE SHOTTON WORKS of British Steel Corporation, built on reclaimed land at the foot of the Dee estuary in Flintshire, are well known to many road hauliers in the North West and, indeed to visitors from all over the world. Up to 80 per cent of the 30,000 tons of finished steel produced in an average week, is dispatched by road, a third of it in Shotton's own vehicles and the balance by hired haulage.

Steel works are exciting places to visit and Shotton is no exception. The nonchalance with which veteran steel workers convert heated steel ingots in the slabbing mill to slabs 20ft to 24ft long X 25in. to 55in, wide and to 9in. thick is astonishing to visitors. The process, despite the sophistication of the costly steel rolling machines, is akin to the pre-war grocers' butter-patting craft, On the 980-acre site with 120 acres of covered buildings there are 68 miles of rail tracks and 20 miles of internal roads.

At Shotton it is cheaper and quicker to move semi-finished steel within the works by road, in the necessary quantities and frequencies, than by rail.

The iron and steel making section of the works depends very largely on rail transport for the major movements of coal, ore. hot metal (iron) and steel ingots, while the finishing mills lean heavily towards road transport for the movement of semi-finished steel between Mills and coating departments, 14,000 to 15,000 tons by road compared with 3000 to 4000 tons by rail per week.

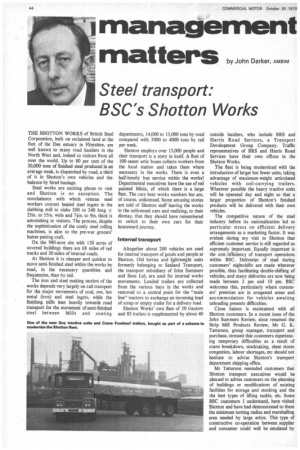

Shotton employs over 13,000 people and their transport is a story in itself. A fleet of 100-seater artic buses collects workers from the local station and takes them where necessary in the works. There is even a half-hourly bus service within the works1 Departmental executives have the use of red painted Minis, of which there is a large fleet. The cars bear works numbers but are, of course. unlicensed. Some amusing stories are told of Shotton stall leaving the works in the unlicensed cars and realizing, to their dismay, that they should have remembered to switch to their own cars for their homeward journey.

Internal transport

Altogether about 200 vehicles are used for internal transport of goods and people at Shotton. Old lorries and lightweight units formerly belonging to Sealand Transport, the transport subsidiary of John Summers and Sons Ltd, are used for internal works movements. Loaded trailers are collected from the various bays in the works and removed to a central point for the -main line" tractors to exchange an incoming load of scrap or empty trailer for a delivery load.

Shotton Works' own fleet of 50 tractors and 85 trailers is supplemented by about 40 outside hauliers, who include BRS and Harris Road Services, a Transport Development Group Company. Traffic representatives of BRS and Harris Road Services have their own offices in the Shotton Works.

The fleet is being modernized with the introduction of larger but fewer units, taking advantage of maximum-weight articulated vehicles with coil-carrying trailers. Wherever possible the heavy tractive units will be operated day and night so that a larger proportion of Shotton's finished products will be delivered with their own vehicles.

The competitive nature of the steel industry before its nationalization led to particular stress on efficient delivery arrangements as a marketing factor. It was evident during my visit to Shotton that efficient customer service is still regarded as supremely important. Equally important is the cdst /efficiency of transport operations within BSC. Deliveries of steel during customers' nightshifts are made wherever possible, thus facilitating double-shifting of vehicles, and many deliveries are now being made between 2 pm and 10 pm. BSC welcomes this, particularly where customers' premises are in congested areas and accommodation for vehicles awaiting unloading presents difficulties.

Close liaison is maintained with all Shotton customers. In a recent issue of the John Summers Review, since renamed the Strip Mill Products Review, Mr G. K. Tatterson, group manager, transport and purchase, stressed that customers experiencing temporary difficulties as a result of crane breakdown, stocktaking, sheet stores congestion, labour shortages, etc should not hesitate to advise Shotton's transport department shipping office.

Mr Tatterson reminded customers that Shotton transport executives would be pleased to advise customers on the planning of buildings or modifications of existing facilities for storage and stocking and the the best types of lifting tackle, etc. Some BSC customers I understand, have visited Shotton and have had demonstrated to them the minimum turning radius and marshalling area needed by large artics. This type of constructive co-operation between supplier and consumer could well be emulated by

other industries.

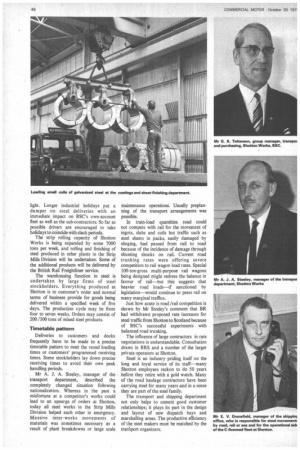

Mr E. V. Dransfield, road transport and shipping manager, is responsible for steel movements by road, rail or sea and for the operational side of the C-licensed fleet. Shotton Works' own-account fleet concentrates on customer deliveries within 100 miles. About 12 per cent of the return journeys are loaded, baled scrap in various grades being collected from customers or other supply sources. The largest scrap baler in Europe is shortly to be installed at Shotton. It will produce scrap in 3-ton bundles for the open-hearth furnaces. Ore supplies, some tons a year, are railed from Birkenhead.

Good and bad 'drops' The transport section receives a copy of a traffic manifest showing goods awaiting dispatch. This is married with a copy of the customer's order and a decision is made as to mode of transport if this is not specified by customer. The own-account fleet copes with many short-distance deliveries but ease of turnround is a factor. A few large customers take 8 or 10 hours to off load steel occasionally. Every effort is made to share out the good and bad "drops" fairly among the independent hauliers.

On average, vehicles reporting to Shotton Works for traffic are loaded and leave the works within 11 hours. There are a dozen different loading points and a load can involve two or three pick-ups.

Mr Dransfield's biggest problem is keeping everyone happy when traffic is light. Longer industrial holidays put a damper on steel deliveries with an immediate impact on BSC's own-account fleet as well as the sub-contractors. So far as possible drivers are encouraged to take holidays to coincide with slack periods.

The strip rolling capacity of Shotton Works is being expanded by some 7000 tons per week, and rolling and finishing of steel produced in other plants in the Strip Mills Division will be undertaken. Some of the additional products will be delivered by the British Rail Freightliner service.

The warehousing function in steel is undertaken by large firms of steel stockholders. Everything produced at Shotton is to customer's order and normal terms of business provide for goods being delivered within a specified week of five days. The production cycle may be from four to seven weeks. Orders may consist of 200 /300 tons of mixed steel products.

Timetable pattern Deliveries to customers and docks frequently have to be made to a precise timetable pattern to meet the vessel loading times or customers' programmed receiving times. Some stockholders lay down precise receiving times to avoid their own peak handling periods.

Mr A. J. A. Steeley, manager of the transport department, described the completely changed situation following nationalization. Whereas in the past a misfortune at a competitor's works could lead to an upsurge of orders at Shotton, today all steel works in the Strip Mills Division helped each other in emergency. Massive inter-works movements of materials was sometimes necessary as a result of plant breakdowns or large scale maintenance operations. Usually preplanning of the transport arrangements was possible.

In train-load quantities road could not compete with rail for the movement of ingots, slabs and coils but traffic such as steel sheets in packs, easily damaged by slinging, had passed from rail to road because of the incidence of damage through shunting shocks on rail. Current road trunking rates were offering severe competition to rail wagon load rates. Special 100-ton-gross multi-purpose rail wagons being designed might redress the balance in favour of rail—but this suggests that heavier road loads—if sanctioned by legislation—would continue to press rail on many marginal traffics.

Just how acute is road /rail competition is shown by Mr Steeley's comment that BR had withdrawn proposed rate increases for steel traffic from Shotton to Scotland because of BSC's successful experiments with balanced road trunking.

The influence of large contractors in rate negotiations is understandable. Consultation draws in BRS and a number of the larger private operators at Shotton.

Steel is an industry priding itself on the long and loyal service of its staff—many Shotton employees reckon to do 50 years before they retire with a gold watch. Many of the road haulage contractors have been carrying steel for many years and in a sense they are part of the steel family.

The transport and shipping department not only helps to cement good customer relationships; it plays its part in the design and layout of new dispatch bays and marshalling areas. The productive efficiency of the steel makers must be matched by the tran'sport organizers.