VEHICLE SELECTION GUIDE TO BUYERS.

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

s New. Fee

S0 RAPID is the growth in the transport by road of goods and passengers that there is a continual flow of new-comers into the industry, and many of them, naturally, have but a very vague idea of the types of vehicle hest suited to meet their particular requirements. It is often in this initial step of buying that the novice takes a line which, unless lie be the fortunate possessor of a large capital, may eventually lad him away from the path of success; it might even land him into the Bankruptcy Court.

At the commencement, he will, no doubt, receive advice from many quarters, some probably from friends who wish to dispose of second-hand vehicles of doubtful age and of still more doubtful value; such advice from interested persons should be treated with great caution. We do not deprecate the employment by the beginner of a second-hand vehicle, as it may give him a most useful schooling by which he will benefit inthe years which follow ; but we make this reservation : that advice on the matter should be sought from some q'tialified friend or engineer consultant who has no axe to grind.

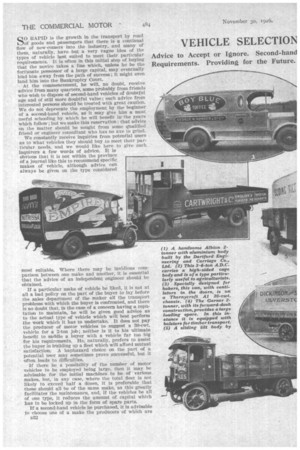

We constantly receive inquiries from potential users as to what vehicles they should buy to meet their particular needs, and we would like here to give such inquirers a few words of advice. It is obvious that it is not within the province of a journal like this to recommend specific makes of vehicle, although advice can always be given on the type considered

most suitable. Where there may be invidious comparison between one make and another, it is essential that the advice of an independent engineer should be obtained.

If a particular make of vehicle be liked, it is not at all a bad policy on the part of the buyer to lay before the sales department of the maker all the transport problems with which the buyer is confronted, and there Is no doubt that, in the case of a concern having a reputation to maintain, he will be given good advice as to the actual type of vehicle which will best perform the work which it has to undertake. It does not pay the producer of motor vehicles to suggest a 30-cwt. vehicle for a 2-ton job ; neither is it to his ultimate benefit to saddle a buyer with a vehicle far too big for his requirements. He, naturally, prefers to assist the buyer in &adding up a fleet which will afford mutual satisfaction: A haphazard choice on the part of a potential user may sometimes prove successful, but it often leads to difficulties.

If there be a possibility of the number of motor vehicles to be employed being large, then it may be advisable for the initial machines to be of various makes, but, in any case, where the total fleet is not likely to exceed half a dozen, it is preferable that these should all be of the same make, as this greatly facilitates the maintenance, and, if the vehicles be all of one type, it reduces the amount of capital which has to be locked up in the form of spare parts.

If a second-hand vehicle he purchased, it is advisable to choose one of a make the producers of which are u32

still in active operation ; otherwise, spare parts may be difficult to obtain or unduly expensive. It must always be remembered that first cost is not the most important. A little more expended at the beginning may save itself over and over again before the vehicle reaches the end of its useful life. A low mileage on petrol and oil and heavy maintenance costs may quickly outweigh any saving in first cost, although this not does necessarily imply that cheapness means bad quality, for it may have been achieved by good design, the avoidance of unnecessary complication and efficient means for production..

The potential user who has read so far will probably be thinking: "All this may be interesting, but it does not tell me how I can come to any decision as to what type of vehicle it would be best for me to buy," and we will now endeavour to help him out of this difficulty.

. First of all, it is esSential that he should make a thorough analysis of his requirements, the class or classes of goods to be carried, the probable weight of each load, the distances to be traversed, and the number• of delivery or collection halts per journey. lie must take into consideration the fact that the average speed • between halts will be much greater than, say, by horsed vehicle—probably in the ratio of four to one. So that if loading and unloading can be expedited, and a reasonable time allowed for these opera tious, a fairly accurate computation of the number of motor vehicles required to perform the same work can be made.

If it be a question of competing with the railway, it must not be forgotten that the loads are carried from door to door, so that the saving is not only one of time, but of convenience, and in the avoidance of a large proportion of the risks due to handling, as there are only two in the case of the motor vehicle as compared with at least four, and often more, in transference, when railway transport is employed.

In computing the number of vehicles to be employed or -the total tonnage to be carried, attention must be given to the fact that the provision of a -fast and efficient means of transport may rapidly result in an expansion of business. Where several vehicles are to be employed, it is not a matter of great importance, as it merely means an addition to the fleet, but in the case of a man who has probably, after saving for a considerable time, managed to obtain a vehicle, such expansion may prove more embarrassing than otherwise, for it may mean overworking or overloading his one vehicle until such time as a second can be commissioned. Such a problem is more likely to confront a tradesman than any other user, for there is no doubt that the expansion of many small businesses is directly attributable to the employment of the fast transport unit which delivers the goods almost as quickly as if they were carried home by the customers themselves.

Looking at the matter from this point of view, it will

be seen that it is not always advisable to purchase a vehicle exactly suited to present requirements. On the other hand, an increase of business does not always mean that individual loads have to be larger, and it is useless buying, say, a 3-tonner if the average loads to be carried weigh only 30 cwt. and if the delivery points are so far spent that the quantities for the two places cannot economically be carried on the same vehicle; so that it would be far better to employ two machines each of 30-cwt. or 2-ton capacity, but it must not be thought that those can be obtained at the same mice as a single vehicle capable of carrying twice the load. In addition, the cost of transport per ton-mile is increased by the fact that a second driver, and possibly a second boy, must be employed.

Where two vehicles are to constitute the first step in the inauguration of a fleet, it is usually preferable to have them of different load capacities, so that neither is employed inefficiently. It may be that two vehicles of entirely different classes, such as the motorcycle and sidecar for weights up to a maximum of 4 cwt., and the light van carrying, say, 10 cwt. may be employed. In another case, where tile loads are of a heavier • nature, alight van may be used in conjunction with a lorry. There are numbers of different combinations, and it is quite unnecessary to enumerate all of them. We give examples merely to bring to the notice of the buyer the importance of employing a vehicle which fits the load.

For those who wish to make a selection of chassis, we would recommend a perusal of our Tablas of Specifications which were contained in our 1927 Outlook Number, published on November gth, and to employ these in conjunction with our Tables of Operating Costs, which are issued free on request and will also be republished in a revised form early in December. These cost tables constitute a guide to the user and buyer the importance of which cannot be overestimated. They are, naturally, average figures derived from a study of conditions obtaining all over the country. Consequently, some users may consider them slightly on the high side, others slightly on the low, and it should be the object of those controlling transport to achieve even better figures than those published. They will assist the buyer in his derision as to whether to purchase a single machine of large capacity or, say, two smaller models, but he must remember that price is not the only consideration and that the smaller vehicles may each be able to cover perhaps twice the mileage.

We will now consider the pros and eons of the various means of transport. For the lightest loads, where the delivery radius is small, and the bulk of the individual package but little, the motorcycle and sidecar combination is a cheap and practicable machine, but it presents the disadvantages "that it affords little or no protection to the driver and the ratio of labour cost to vehicle capacity is high. The heaviest load capacity of such a machine is in the neighbourhood of ri cwt.

Next in order comes the three-wheeled pareelear, but at .present there is little choice in such vehicles, although they would appear to possess undoubted merit, as they can be made to afford a fair degree of comfort for the driver and can be constructed to carry 8 cwt. It is certain that the vast majority of comniercial vehicles is light vans of load capacities ranging from 7 cwt. to 1 ton. Such vehicles are fast, comparatively cheap to operate, lend themselves to neat ,and even ornate bodies, and afford excellent protection both for the articles carried and the drivers.

The employment of larger vans is mainly a question of the classes of goods transported. Drapery, being light for its bulk, demands a large-capacity body on a comparatively light chassis, whilst ironmongery, for instance, is much heavier for its bulk, and the vehicle employed must be in accordance.

The distinction between the large van and the lorry is partly one of appearance, but, mainly, one of weather protection for the goods and convenience in loading and unloading. A lorry does not lend itself to classes of work where the frequent handling of the load is. required. It is much easier to open the doors of a van than to drop a tailboard, and the van also lends itself to the stacking of parcels in a way not possible with a lorry. If necessary, a van may also be furnished with shelves to facilitate such an arrangement, and side doors can be provided in addition to those at the back.

As the sphere of heavier loads is reached, the choice of vehicles beComes wider, and it is necessary to decide between petrol and steam vehicles and petrol tractors drawing trailers. The last-mentioned means is one that has of late greatly extended its scope, and loads up to 10 tans are being carried by suitably designed trailers which impose a portion of the load on to the rear of the tractor, so giving it increased adhesion. Such a method presents the advantage that where the distances are comparatively short one tractor may be employed with a number of trailers, thus cutting down time losses through the power unit being held up While unloading and loading are in progress. Tactor haulage is being employed successfully for the transport of paper, furniture, etc.

T_Intil recently the steam vehicle was considered suitable only for heavy transfiort at moderate speeds over comparatively short distances, but hero, again, evolution has been at work and the latest examples of steam wagon are almost as speedy as the petrol vehicle, fare extremely reliable, cheaper to run and use a home-produced fuel (although this is not available in great quantities at the present moment), the disadvantages being that they require rather more attention from the drivers, must be assured of ample supplies of water and are not always appreciated at their true value by other users of the road. They are particularly good, however, where trailer haulage is essential.

There are, of course petrol vehicles which have been specially designed to haul trailers, and these should not be overlooked.

For still heavier loads, up to 12 tens, a most satisfactory form of vehicle is the tractor-trailer, which can be obtained to run either on petrol or steam, and it must not be forgotten that the rigid form of six-wheeler is now coming to the fore for the heavier loads.

There are till two other types of transport media which mast receive consideration.. These are the battery electric vehicle and the smallwheeled, large-capacity vehicle of the S.D. Freighter type.

We have always considered the electric vehicle as a very satisfactory form of transport in those places where current is available at a moderate figure. Its sphere of action is, of course, limited to approximately 50 miles per day, or, perhaps, a little more if a booster charge be given at the luncheon interval. Its maximum speed is comparatively low, but it is an ideal vehicle for employment in traffic, and where there is a large number of stops per mile its rapid acceleration enables a good average speed to be maintained. It is also noiseless, clean and easily controlled.

The small-wheeled vehicle is easentially one for shortdistance transport in and around towns. It can carry large loads at a IOW cost and occupies a much smaller amount of road ipace for its capacity than does the ordinary vehicle. Consequently, it can be manoeuvred in restricted areas, whilst presenting the additional advantage that its platform is so low as greatly to facilitate loading and unloading from the ground.

Apart from the problem of selecting a suitable type of vehicle, the intending user should make preparations for its reception and maintenance and with the great increase in the employment of motor vehicles, garage accommodation is not always easy to find.

Much of the responsibility for the success or failure of a vehicle must naturally depend upon the driver employed. Good drivers are not rare, but neither are had ones, and it is advisable to use a considerable amount of discretion in making a selection. A higher wage to a good man may, in the end, effect a considerable saving not only in respect of the cost of running the vehicle. but in the avoidance of irritating delays. A vehicle owner can seldom accompany it, consequently, he must rely to a great extent upon the good faith of the driver.