At the turn of the century hundreds of working tin

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

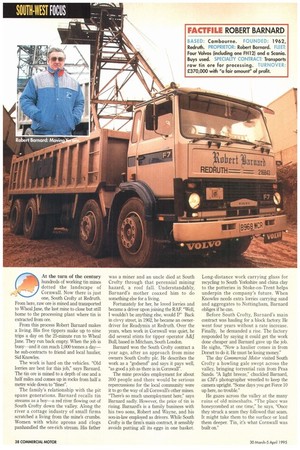

mines dotted the landscape of Cornwall. Now there is just one, South Crofty at Redruth. From here, raw ore is mined and transported to Wheal Jane, the last mine to close but still home to the processing plant where tin is extracted from ore.

From this process Robert Barnard makes a living. His five tippers make up to nine trips a day on the 25-minute run to Wheal Jane. They run back empty When the job is busy—and it can reach 1,000 tonnes a day— he sub-contracts to friend and local haulier, Sid Knowles.

The work is hard on the vehicles. "Old lorries are best for this job," says Barnard. The tin ore is mined to a depth of one and a half miles and comes up in rocks from half a metre wide down to "fines".

The family's relationship with the pit spans generations. Barnard recalls tin streams as a boy—a red river flowing out of South Crofty down the valley. Along the river a cottage industry of small firms scratched a living from the mine's crumbs. Women with white aprons and clogs panhandled the ore-rich stream. His father was a miner and an uncle died at South Crofty through that perennial mining hazard, a roof fall. Understandably, Barnard's mother coaxed him to do something else for a living.

Fortunately for her, he loved lorries and became a driver upon joining the RAF. "Well, I wouldn't be anything else, would I?" Back in civvy street, in 1962, he became an ownerdriver for Readymix at Redruth. Over the years, when work in Cornwall was quiet, he did several stints for tipper operator A&J Bull, based in Mitcham, South London.

Barnard won the South Crofty contract a year ago, after an approach from mine owners South Crofty plc. He describes the work as a "godsend" and says it pays well, "as good a job as there is in Cornwall".

The mine provides employment for about 300 people and there would be serious repercussions for the local community were it to go the way of all Cornwall's other mines. "There's so much unemployment here," says Barnard sadly. However, the price of tin is rising. Barnard's is a family business with his two sons, Robert and Wayne, and his son-in-law employed as drivers. While South Crotty is the firm's main contract, it sensibly avoids putting all its eggs in one basket. Long-distance work carrying glass for recycling to South Yorkshire and china clay to the potteries in Stoke-on-Trent helps underpin the company's future, When Knowles needs extra lorries carrying sand and aggregates to Nottingham, Barnard obliges if he can.

Before South Crofty, Barnard's main contract was hauling for a block factory He went four years without a rate increase. Finally, he demanded a rise. The factory responded by saying it could get the work done cheaper and Barnard gave up the job. He sighs, "Now a haulier comes in from Dorset to do it. He must be losing money."

The day Commercial Motor visited South Crofty a howling gale swept across the valley, bringing torrential rain from Praa Sands. "A light breeze," chuckled Barnard, as CM'S photographer wrestled to keep the camera upright. "Some days you get Force 10 up here, no trouble."

He gazes across the valley at the many ruins of old mineshafts. "The place was honeycombed at one time," he says, "Once they struck a seam they followed that seam. It might take them to the surface or lead them deeper. Tin, it's what Cornwall was built on."