ALMS TO ARMENIA

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

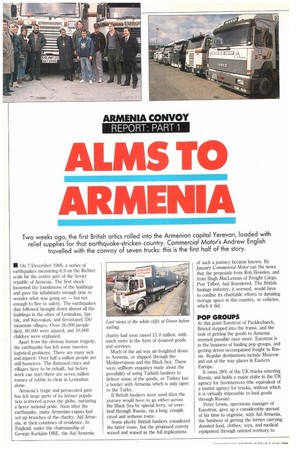

Two weeks ago, the first British artics rolled into the Armenian capital Yerevan, loaded with relief supplies for that earthquake-stricken country. Commercial Motor's Andrew English travelled with the convoy of seven trucks: this is the first half of the story.

IN On 7 December 1988, a series of earthquakes measuring 6.9 on the Richter scale hit the centre part of the Soviet republic of Armenia. The first shock loosened the foundations of the buildings and gave the inhabitants enough time to wonder what was going on — but not enough to flee to safety. The earthquakes that followed brought down almost all the buildings in the cities of Leninakan, Spitak, and Kirovakan, and devastated 350 mountain villages. Over 26,000 people died, 80,000 were injured, and 10,000 children were orphaned.

Apart from the obvious human tragedy, the earthquake has left some massive logistical problems. There are many sick and injured. Over half a million people are still homeless. The flattened cities and villages have to be rebuilt, but before work can start there are seven million tonnes of rubble to clear in Leninakan alone.

Armenia's tragic and persecuted past has left large parts of its former population scattered across the globe, nurturing a fierce national pride. Soon after the earthquake, many Armenian expats had set up branches of the charity, Aid Armenia, in their countries of residence. In England, under the chairmanship of George Kurkjian OBE, the Aid Armenia charity had soon raised £1.8 million, with much more in the form of donated goods and services.

Much of the aid was air-freighted down to Armenia, or shipped through the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. There were stillborn enquiries made about the possibility of using Turkish hauliers to deliver some of the goods, as Turkey has a border with Armenia which is only open to the Turks.

If British hauliers were used then the journey would have to go either across the Black Sea by special ferry, or overland through Russia, via a long, complicated and arduous route.

Some plucky British hauliers considered the latter route, but the proposed convoy waxed and waned as the full implications

of such a journey became known. By January Commercial Motor ran the news that the proposals from Rob Howden, and from Hugh MacLennan of Freight Cargo, Port Talbot, had floundered. The British haulage industry, it seemed, would have to confine its charitable efforts to donating storage space in this country, or vehicles, which it did.

POP GROUPS

At this point Eurotrux of Pucldechurch, Bristol stepped into the frame, and the task of getting the goods to Armenia seemed possible once more. Eurotrux is in the business of hauling pop groups, and getting driver-accompanied freight to Russia. Regular destinations include Moscow and out of the way places in Eastern Europe.

It owns 39% of the UK trucks entering Russia, and holds a major stake in the UK agency for Sovinteravto (the equivalent of a tourist agency for trucks, without which it is virtually impossible to haul goods through Russia).

Peter Lewis, operations manager of Eurotrux, gave up a considerable amount of his time to organise, with Aid Armenia, the business of getting the lorries carrying donated food, clothes, toys, and medical equipment through untried territory to Yerevan, capital of Armenia.

Lewis enlisted the help of BM Transport of London, TransArn Trucking of Norfolk, Fransen Transport of West Midlands, Commercial Motor, the Aid Armenia charity, and the resources of his own company to get the trip underway. MacLennan approached Iveco Ford for a vehicle and was duly handed a former Iveco Ford 190-36 demonstrator to take to Armenia. Sealink British Ferries donated free passage to Calais and Kurkjian came up with some of the running costs.

Other sponsors included: Petter Refridgeration, The Royal Nedlloyd Group, Leyland Daf, Gray and Adams Atlas Refrigerated Trailers and Trailerent:

TIMETABLES

Dates became revised, time tables were put back, but the trip was definitely on, and 1 March sees the seven trucks lined up on the quay at Dover docks ready for the off, having loaded with the help of the pupils and staff of St Josephs College of Birkfield, Ipswich, during the previous two days.

Steve Dawson, Mick Ward, Rod Wilson and Mark Deakin of Eurotrux are driving Scania 112 4x2s; Fraser Aitken of Trans. Am Trucking drives a Scalia 112 4x 2; Peter Dyke of Fransen Transport has a Oaf 2800 6x2 twinsteer, and Hugh MacLennan of Freight Cargo drives the Iveco Ford 190.36 4x2. All are desperately trying to sort out their papers, and getting to know one another in the chaotic time before sailing. Central Trailer Rental has lent the convoy three triaxle international tilts, and these, and the other box semitrailers are loaded to around 28 tonnes. The proposed route is through France, Belgium, Holland, West and East Germany, Poland, and then into Russia. Estimated distance is around 5,000km, and the estimated duration is around nine days, depending on the weather.

Once the dock speeches are over, the convoy is blessed by Bishop Yeghishe Gizirian, Apostolic Delegate of His Holiness, Vasken I, Catholicos of all Armenians, in Etchrniadzin, Armenia, whose name check alone nearly made us miss the ferry!

The final questions are asked, the trucks are started, and the ferry is loaded. Doors shut, wave goodbye, and we're off. Now the first thing to remember about any truck journey that goes through Europe, no matter how auspicious, is that the "corridors" through France, Belgium, Holland, and West Germany are stultifyingly boring. We manage to remain awake and rumble our way through to Lockeren services, Belgium for a good meal on the first day.

Convoy running is alien to most hireand-reward hauliers. Rock-and-roll truckers have to adjust to this method, because of the nature of their work, but in spite of this, the party is already involved in a lively discussion on the best way to get from A to B, the order of the trucks in the convoy, and which truck has a working cigarette lighter. Mick Ward, as driver one (D1) has to make the final decision. It is plan A, whatever that is.

Notes for day two indicate that 8.50am sees us through the Belgian/Dutch border, and 09:45 sees us through the Dutch/ German line. Also making an appearance through the day are stops for tea, breakfast, coffee, brunch, lunch, fuel and windscreen washer additive. These boys know how to do it right.

FORBIDDING

By 18:20 we reach the East German border. From the outside looking in East Germany looks grim, forbidding, and made of concrete, an impression that remains and is reinforced with the smell of what seems like burning banana skins once inside. The Helstedt border crossing is large, with over 41 lanes and impressive administrative buildings. The guards seem friendly enough, however, and after paying 5 DM for our visas, getting the carnets stamped, and a small discussion about who is to run first, we get on our way into COMECON, overnighting in the last service area before Berlin.

Day three dawns wet and cold. Steve has lost his cigarettes (a recurrent theme of the trip), and he has a drive axle puncture. The tyre is ruined, and the spare is from a steered axle. Mike takes stock of the tyre situation: Hugh, Fraser, Rod and Peter's trucks have good tyres, but the covers on the Scanias of Mick, Steve, and Mark have seen better days. In particular, Steve's drive axle tyres are recut remoulds with the remaining tread looking like a long slice of bacon wrapped around the wheel.

This is not the best situation to be in when facing long journeys over unknown terrain in adverse weather conditions. They decide to change a number of the tyres in Russia.

At 09:45 Steve calls the others on the CB radio, "How are we doing?" The trucks slowly pull out onto the Berliner Ring road en route for the Polish border, which is reached by 12:30. As we fill out visa applications we discuss the problems faced by Hugh in the Iveco.

Earlier in the day, the big Iveco had blown a fuse in the ignition circuit which Steve, an ex-Iveco workshop manager, had tracked down to an earth in the warning lamp for the ZF 16-speed gearbox. The truck needs a new fuse every time it is started and Hugh had wanted to call out Iveco service in Berlin to get the fault looked at. Instead, we pressed on for the Polish border, and now the Iveco's fuse problem, and the earlier failure of its driver's croor electric window, look ominous. "If we only get one thing wrong per day, then we should be there in nine days," says Hugh, cheerfully.

The Polish border crossing takes about an hour, and an hour after that we stop for lunch. Poland is a land geographically bonded to the Eastern bloc but culturally attached to Europe. All the drivers find the country a refreshing change after the sights and smells of East Germany. The countryside is green, the houses look homely and wildlife is abundant.

Hugh leaves the Iveco's engine running during lunch, although we soon learn how to take the one remaining fuse out before stopping to prevent it blowing on restarting. By 20:00 we have reached a truck stop about 100km before Poznan. It is full, and the addition of seven British trucks (and the attendant hard currency that implies) impels the staff and the police into action to find us spaces.

Several hundred kilometres of pleasant Polish vistas roll past, and by 16:00 on Sunday we reach the llan queue for the Russian border.

Make no mistake about it, this is a diresome place indeed. You can be assured that the producers of films like Funeral in Berlin and The Spy who came in from the Cold did not get it wrong. Concrete emplacements, guards with very real looking guns and hungry-looking dogs march round the vehicles. The twilight fields that surround the border are full of foreboding. What is out there? Bears, mines, perhaps even packs of wolves? Looking straight ahead, and whistling brave tunes, we concentrate on the business ahead.

ON TNE HOUSE In fact the crossing only takes two hours. When we reach the inspection shed, there is an English-speaking official there who speeds us through the formalities of customs declarations, carnets, vetinary inspections, insurance for Russian roads, visas, and Sovintervato service books. He knew where we were during the day, our names, and the full details of the trip, but before we have time to ponder the Orwellian nature of this, he hands us a Sovinteravto service book, and says, roughly translated, "have this on me".

This is a massive act of generosity from the Russians. It means that we are able to get diesel, servicing, lntourist hotel accommodation and food, all at the expense of the state. The trucks have all been sponsored for these costs by the Aid Armenia charity, although as it turns out the sponsorship money just about covers the cost of the damage to the trucks when we get into Russia.

But more of that next week. . . 0 by Andrew English