Old engine is up to new task

Page 33

Page 34

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

FOLLOWING its spectacular debut on the eve of last year's Motor Show, Leyland's Roadrunner seems to be making its mark in the fiercely contested 7.5 tonne gross weight market segment.

It has a stylish new cab, a well designed chassis which is liked by bodybuilders and, at 4.90 tonnes, its body/payload potential is the highest of any vehicle we have tested at this weight so far. All are essential ingredients for success.

Leyland has two 7.5 tonne models; the 72.4kW (97hp) 8.10 and the 86kW (115hp) 8.12 version, which Leyland provided for our feature. It is powered by the Bathgate-built 6.98NV 5.6 litre engine which, with the gearbox and rear axle, are components carried over from the long-serving Terrier range.

Although the 98 Series engine has a rather chequered history, in recent years it has achieved the high standard of reliability sufficient to give Leyland the confidence to build it into the new range.

The 8.12's performance around our tough Welsh route suggested that the engine's inclusion is certainly justified and that, despite a general trend towards more horsepower, the 98-series will more than hold its own until a quieter, more fuel-efficient replacement is found.

In-cab noise levels of 79 and 84dB(A) at 50 and 70 mph were higher than the 76 and 79dB(A) respectively of the MercedesBenz 8.14, but the rate of acceleration seemed very much the same.

The Roadrunner's maximum geared speed is given as 103km/h (64mph), but like so many other diesel engines, governor run-out allowed it to reach 112km/h (70mph) on over-run quite comfortably.

The final drive ratio is 4.36:1, the lowest in the group. This could explain why the 8.12 fared so badly on the motorway. Operators should bear in mind that Leyland does not offer a lower differential.

For such a dated engine it was not short of pace, matching exactly the running times of the Mercedes 8.14 tested last October. It covered the 210.2 miles in four hours 37 minutes at an average speed of 73.63km/h (45.53mph) under similar weather conditions.

None of the 7.5 tonners tested in this or the previous group had been quicker on either the motorway or A-road sections, and the 8.12's hill climb times compared well with them all. It took the hills on our route at Monmouth in 2 min 35 sec in fifth gear and at Wantage in 2 min 40 sec in second.

Laden to its maximum gross weight the 8.12 pulled away in second gear without a pause, but on anything of an incline first had to be used.

Quick running urban traffic occasionally revealed too much of a jump between second and third gears. But once the driver is aware of this he can compen sate by delaying his gear change until faster engine and road speeds are attained. With out a rev counter the driver must gauge engine speed by ear.

On long gradients the Roadrunner was inclined to lug down — what a pity that Ley land could not fit a rev counter to help budding heavy goods vehicle drivers to exploit this and at the same time possibly improve fuel consumption.

This is one area where the 8.12 fell behind some of the competition. As expected, motorway running took its toll on fuel, bringing its figures down to 20.08 lit/100km (14.73mpg) on the M4 stretch. On A-roads however it produced its best figures — 16.71 lit/100 km (16.91mpg) — which for that section is not so far be hind the 16.021it/100krn (17,43mpg) of the 110hp Ford Cargo 0811 that excelled in the previous 7.5 tonne group test.

Its handling certainly lived up to its lively image, with the combined Burman steering box and ZF integral power assistance giving just the right amount of feel without being over-sensitive. When worked hard at low engine speeds it coped very well, but made loud swishing noises. The narrow turning circle of 12.3m (40.36ft) kerb-to-kerb helped too when negotiating tight turns like those in Ledbury and Cheltenham.

Braking steadily from 50mph occasionally produced a slight shuddering from the front wheels, but this disappeared inexplicably towards the end of the test. Overall, the Roadrunner's air-over-hydraulic brakes felt well up to the required standard, bringing the vehicle up sharply when called upon to do so on two occasions in Hereford town centre.

The parabolic springs fitted on all wheels gave a good ride level, especially on some of the undulating roads in the Wantage area. But there was a small amount of body roll on the winding sections. Leyland will be offering an anti-roll bar as an option to help counter this.

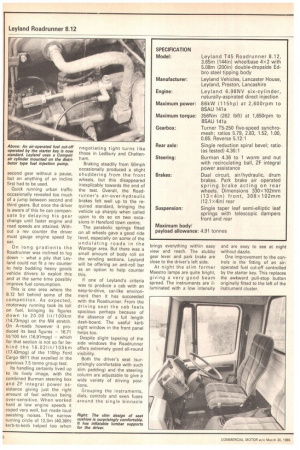

If one of Leyland's criteria was to produce a cab with an easy-to-drive, car-like environment then it has succeeded with the Roadrunner. From the driving seat the cab feels spacious perhaps because of the absence of a full length dash-board. The useful kerb sight window in the front panel helps too.

Despite slight tapering of the side windows the Roadrunner offers extremely good all-round visibility.

Both the driver's seat (surprisingly comfortable with such slim padding) and the steering column are adjustable to give a wide variety of driving positions.

Grouping the instruments, dials, controls and even fuses around the single binnacle brings everything within easy view and reach. The stubby gear lever and park brake are close to the driver's left side.

At night the slim former Maestro lamps are quite bright, giving a very good beam spread. The instruments are illuminated with a low intensity and are easy to see at night without dazzle.

One improvement to the controls is the fitting of an airoperated fuel cut-off controlled by the starter key. This replaces the awkward pull-stop button originally fitted to the left of the instrument cluster.