THE FUTURE OF THE STEAM VEHICLE.

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Completion of an Article the First Part of which Appeared Last Week. Boilers Old and New. BUilding Steam Wagons to Run on Pneumatics.

IN THE first portion of this article the writer gave a brief résumé of steam-wagon history, which led up to the consideration of important improvements in design. Reasons were given for the great success of the overtype, these being followed by notes on the relative merits of chain and shaft drive for the transmission and the essential differences between the torque curves of the petrol engine and steam engine. It was pointed out that the unladen weight of the average steam wagon is 50 per cent. greater than that of the petrol lorry of the same nominal carrying capacity and the weight factors were discussed with a view to their reduction. That which concerned the boiler will now be dealt with.

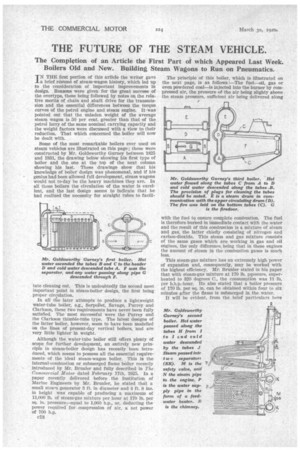

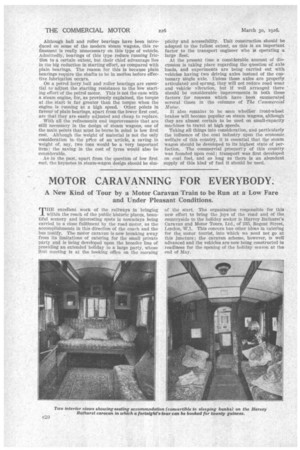

Some of the most remarkable boilers ever used on steam vehicles are illustrated on this page; these were constructed by Mr. Goldsworthy Gurney between 1825 and 1831, the drawing below showing his first type of boiler and the one at the top of the next column showing his last. These drawings show that his knowledge of boiler design was phenomenal, and if his genius had been allowed full development, steam wagons would not to-day be the heavy machines they are. In all these boilers the circulation of the water is excellent, and the last design seems to indicate that he had realized the necessity for straight tubes to facili tate cleaning out. This is undoubtedly the second most important point in steam-boiler design, the first being proper circulation.

In all the later attdmpts to produce a lightweight water-tube boiler, e.g., Serpollet, Savage, Purrey. and Clarkson, these two requirements have never been fully satisfied. The most successful were the Purrey and the Clarkson thimble-tube type. The latest designs of the latter boiler, however, seem to have been modelled on the lines of present-day vertical boilers, and are very little lighter in weight.

Although the water-tube boiler still offers plenty of scope for further development, an entirely new principle in steam-boiler design has recently been introduced, which seems to possess all the essential requirements of the ideal steam-wagon boiler. This is the Internal-combustion or submerged flame boiler recently introduced by Mr. Brunler and fully described in The Commercial Motor dated February 17th, 1925. In a paper recently delivered before the Institution of Marine Engineers by Mr. Brunier, he stated tha:t a small steam generator 3 ft. in diameter and 4 ft. 8 ins. in height was capable of producing a maximum of 11,000 lb. of steam-gas mixture per hour at 170 lb. per sq. in. pressure, equal to 1,000 h.p., or, deducting the power required for compression of air, a net power of 700 h.p. The principle of this boiler, which is illustrated on the next page, is as follows :—The fuel—oil, gas or even powdered coal—is injected into the burner by compressed air, the pressure of the air being slighty above the steam pressure, sufficient air being delivered along with the fuel to ensure complete combustion. The fuel is therefore burned in immediate contact with the water and the result of this combustion is a mixture of steam and gas, the latter chiefly consisting of nitrogen and carbon-dioxide. This steam and gas mixture consists of the same gases which are working in gas and oil engines, the only difference, being that in these engines the amount of steam in the combustion gases Is much less.

This steam-gas mixture has an extremely high power of expansion and, consequently, may be worked with the highest efficiency. Mr. Brunler stated in his paper that with steam-gas mixture at 170 lb. pressure, superheated to 320 degrees C., the consumption was n lb. per b.h.p.-hour. He also stated that a boiler pressure of 170 lb. per sq. in. can be obtained within four to six minutes after the flame is submerged in the water.

It will be evident, from the brief particulars here given, that this boiler possesses remarkable features. In the first place, the steam. is generated in direct

contact with the flame, and, therea:ore, incrustation or corrosion of heating surfaces—the two most troublesome factors in steam boilers—are non-existent.

No chimney is necessary, as all the products of combustion pass through the engine, consequently, there is no emission of smoke or sparks; the exhaust from the engine will be cleaner than that from an oil engine —due to the presence of more steam. The weight of a boiler capable of generating, say, 1,000 lb. of steam per hour at 250 lb. pressure, superheated to 350 degrees C., shouldbe extremely low, and very little time will be lost in getting up steanli.

• This type of boiler will also lend itself admirably to ' automatic fuel and Water supply—a thing which has been sought after for years. One can almost imagine • such a boiler being fitted with, say, a magneto or some such device, which Will ignite the flame by simply turn ing a starting handle, sufficient steampressure being • generated and the wan' ready to move by the time • the driver has received his instructionsfor ,the day: this will save' a lot of wasted time.

If this can be lieatlized in actual practice, it will revolutionize road transport, for this type of motor would not be dependent upon one class of fuel. In addition to powdered coal, liquid hydrocarbons of a specific gravity between .8 and '1.2 can be lased, ' so that it would operate in practically any part of the world.

After the prodUctien of a satisfactory lightweight holier, the next require

• mem is a suitable engine of _ minimum weight. This can probably best be obtained by adopting a vertical highspeed engine with either piston valves or poppet valves, so as to be capable of working with highly superheated steam. The engine unit must be perfectly balanced, totally enclosed and properly lubricated, these being essential qualities in a high-speed engine. In all probability

it will be found that it is best o adopt a system of forced lubrication, practically on similar lines to present-day petrol engines. Working on these lines, it should be possible to produce an engine of :case Weight • than an equivalent petrol engine.

It may be thought that a turbine would be a suit)1.)le type of engine to use, on account of its perfect balance, but it suffers from a very great drawback, inasmuch as it is, for most practical purposes, essentially a one-speed machine, the vanes having to he designed for a certain nozzle velocity of the steam. It would not possess that high starting torque which is such a valuable characteristic of the reciprocating steam engine, and would require a clutch and four-speed gearbox, as with a petrol motor.

As a big reduction in boiler weight would allow of a pro rata reduction in all parts of tile chassis, it would. no doubt he quite sufficient to have a powerunit capable • .01' developing, say, -50 h.p. at 1,000 r.p.m. In order to .get maximum'benefit from a high-speed engine and to enable the machine to negotiate difficult

• places, it would be necessary to. have either two or • three speeds in the transmission. The most satiefac tory arrangement would probably be an engine and gearbox combined in unit form.

With regard to they transmission, it will probably be found advisable to employ both chain and cardan-shaft drive. Both -these types could be embodied in one ehassis layout, and thereby, standardize the various units and reduce the hut:fiber of parts to the minimum.

The water tank could be considerably reduced, especially as the thermal efficiency of an internal-combustion boiler and high-speed engine would be practically equal to that of a Diesel oil engine, according to Mr. Brunler's figures. The water consumption would probably be in the neighbourhood of 2i gallons per mile for a 7-ton wagon, and as a 50-mile radius would be sufficient for all practical purposes, a tank ef 125 gallons capacity (or n cwt. of water) would be ample.

If an internal-combustion type of boiler were used, it would not be possible to adopt a condenser, as the presence of a large amount of gas in the steam makes condensation impossible. With the high thermal efficiency a condenser is not so essErntial and also it would no doubt be a troublesome unit., especially • in hot weather.

Working upon these lines it should be possible to produce a chassis with an unladen weight of under five tons, capable of carrying a net bead of seven tons. This would bring the chassis within the range of using pneumatic tyres and allow of the necessary high speeds now called for in transport work. There would also be no reason • why this type of machine should not he used for passenger work, especially as it would be immune from the dangerous risk of sudden fire, which is always present on a petrol chassis. How much more comfortattic also would such a vehicle be from the passenger point of view, owing to the smoother running, easier starting and less gear-changing.

Although considerable improvement has been made in the springing of steam wagons, there is still

plenty of scope for further improvement. The chief trouble at the present moment is to give the requisite flexibility at all loads. The ordinary type of laminated spring only functions correctly when the wagon is fully loaded. Various schemes have been tried in order to overcome this defect. In one arrangement a double spring was employed, the second spring coming into operation when the wagon was loaded. Another type of Spring bad the plates arranged with varying cambers,' so that when the wagon Was running light only a certain number ef the top plates were carrying the load, the remainder coming into operation' when the load was applied and the spring fully deflected, as, for instance, the Cary open-plate spring. The trouble with these springs was breakage of the plates, and this was, no doubt, due to the rebound of the spring when the wagon was travelling over rough roads.

The best arrangement of progressive spring yet introduced is that type where the effective length of the spring is reduced as the load increases. This result is obtained by fitting cams to the ends of the spring, and was first used on steam tractors made by Wm. Foster and Co., of Lincoln. Although ball and roller bearings have been introduced on some of the modern steam wagons, this refinement is really unnecessary on this type of vehicle. Admittedly, bearings of this type reduce running fric • lion to a certain extent, but their chief advantage lies in the big reduction in starting effort, as compared with plain bearings. The reason for this is because plain bearings require the shafts to be in motion before effective lubrication occurs.

On a petrol lorry ball and roller bearings are essential to adjust the starting resistance to the low starting effort of the petrol motor. This is not the .ca se with a steam engine, for, as previously explained, the torque at the start is far greater than the torque when the engine is running at a high speed. Other points in favour of plain bearings, apart from the lower first cost, are that they are easily adjusted and cheap to replaCe.

With all the refinements and improvements that are still necessary in the design of steam wagons, one of the main points that must be borne in mind is low first cost. Although the weight of material is not the only consideration in. the price of an article, a saving in weight of, say, two tons would be a very important item; the saving in the cost of tyres would also he considerable.

Asia the past, apart from the question of low first cost, the keynotes in steam-wagon design should be sim

plicity and accessibility. Unit construction should be adopted to the fullest extent, as this is an important factor to the transport engineer who is operating a large fleet.

At the present time a considerable amount of discussion is taking place regarding the question of axle loads, and experiments are being carried out with vehicles having two driving axles instead of the customary single axle. Unless these axles are properly articulated and sprung, they will not reduce road wear and vehicle vibration, but if well arranged there should be considerable improvements in both these factors for reasons which have been enumerated several times in the columns of The Commercial Motor.

It also remains to be seea whether front-wheel brakes will become popular on steam wagons, although they are almost certain to be used on small-capacity machines to travel at high speeds.

Taking all things into consideration, and particularly the influence of the coal industry upon the economic welfare of this country, it is essential that the steam wagon should be developed to its highest state of perfection. The commercial prosnerily of this country was founded upon coal; transport was first developedon coal fuel, and as long as there is an abundant supply of this kind of fuel it should be used.