'No bad vehicles, only some better than others'

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• Avoiding the pitfalls of vehicle selection was the theme of an exceptionally well documented paper by Mr J. E. Farley, group transport engineer of Tate and Lyle Ltd, presented at the Freight Transport Association's fleet planning seminar last vveek.

An audience of 200 transport managers and engineers attended and heard papers by Mr A. J. P. Wilding, FTA chief engineer, and Mr J. Furness, the DoE's assistant chief engineer, chronicling the likely path of future vehicle design trends. Mr Furness had just returned from Brussels, where vehicle regulations were being negotiated.

Mr Fancy took as a starting point that: "Generally there are no bad vehicles, only some better than others." From this he argued that vehicle selection's task was to produce the best equipment for a particular job in which it will have been successful only when a product can be moved in the easiest and most economic way.

The first task in vehicle selection was to write down the objectives which the vehicle had to meet. These should include the following information: payload, type of load, physical size of load, loading and discharge point limitations, distance to be hauled, frequency of operation, terrain to be covered and style of operation. Mr Farley quoted a typical objective: "Need to move 340 tons each eight hours in lots of 20 tons. Commodity raw sugar in bulk from dockside silo to refinery take-in point with a four-mile round trip using route 'A', 17 times per shift of eight hours with a continuous 24 hours per five-day week movement". Sufficient detail was provided here for a selection choice, he said.

Mr Farley pointed out that many different people had an influence on the vehicle buying decision. These could include: the managing director, the board. customer, chief engineer, transport manager. drivers, mechanics, workshop staff and training supervisors. It was important that the right chain of communication was established so that the right questions were asked and the right decision taken.

The following considerations should be taken into account before making a decision: historical records of vehicles currently operating; external matters like environmental pressure, local regulations and Government policy; total costs including initial equipment, operating, maintenance, and standing costs all related to the life of the project; customer demands; the items of company organization which had a bearing on vehicle selection; planning: and depreciation worked out on whatever method was preferred within the company. Having dealt with all these considerations the choice of actual vehicles could be studied.

Examine vehicle weight The first thing to examine was the weight of vehicle involved. Not only should existing requirements be considered but future changes in business and possible legal amendments should be taken into account.

Mr Farley devoted a large part of his paper to the choice between quality and quantity vehicles. He defined the two breeds, Quality: individually built to a particular requirement, usually with a rigid chassis frame. Quantity: with a lighter and more flexible chassis frame construction and built by mass production methods. Mr Farley also listed which makes in his view, fell into which categories. Quality: Foden, Seddon/Atkinson, ERF and Scammell. Quantity: heavy, AEC, Guy, Leyland, .Albion, Mercedes-Benz, Scania and Volvo; light, Bedford, Ford, Chrysler and Leyland Redline. With quality vehicles, said Mr Farley, "reliability is the principal factor being purchased". The disadvantages of quality vehicles were the greater initial cost and the possibility that they might prove too good for the job in hand. "Therefore a quality truck must not be chosen irrespective of the task but tailored to suit it", warned Mr Farley.

Looking at quantity-produced vehicles, Mr Farley said that these had their place where a simple straightforward transport job was involved or where the contract was of short duration (ie: less than five years and where the work was of a local nature and less than annual mileage of 30,000). The specification of such vehicles had to be examined closely and engine power should satisfy the proposed 6 bhp /ton limit. Quantity-produced vehicles were often unsuitable for general haulage because their cabs were designed for distribution work where cross-the-cab access was important. This meant that such a vehicle was often a compromise on general work. The capability of a quality and quantity vehicle was different and until some idea of :he type of duty and terrain likely to be :ncountcred had been reached no choice :ould be made. "Appearance and the ;eneral image of the vehicles are factors which must be weighed and whilst the quality vehicle may give very good reliable ife there is the risk of obsolescence and Inver resistance through not having a 'chicle that appears fashionable," he said.

Another factor which had to be ;onsidered before choosing between quality

and quantity was anticipated life. "The CM Vehicle Replacement Guide is well worth examining and very useful", said Mr Farley. It was important that all companies had a deliberate vehicle replacement policy. Broad criteria like seven years and 250,000 miles for light vehicles, or 10 years and 500,000 miles for heavies could be used to form the basis of a discounted cash flow exercise.

This would determine whether an old vehicle was really in need of replacement. Such an exercise should take into account carrying capacity, cost of licence and insurance, initial costs, percentage loss of time off the road because of maintenance, re-sale value, maintenance costs, mileage, tax allowances, and operating costs.

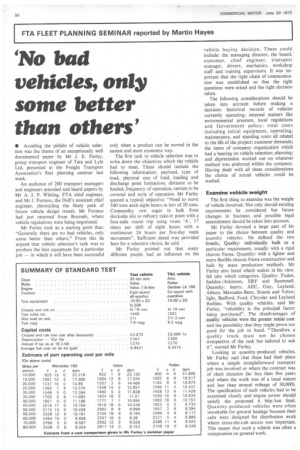

Mr Farley used a slide showing the comparison in maintenance costs of two types of artics. He showed that one group of vehicles cost over £.12,000 more to maintain over five years than the other group. This was directly attributable to the selection decision so it was vitally important to make the correct choice.

Mr Farley said there was a wealth of

written information on the selection of chassis but two main points had to be exactly right if objectives were to be achieved. These were: payload capacity and performance, both physical and economic. It was important when dealing with payload capacity not to accept the specification figures too readily. It was safer to make an individual check. Performance should be considered in relation to impending legislation, like the power-to-weight legislation. Choice of chassis and transmission ratios would be affected by the terrain .to be covered and to illustrate this point Mr Farley produced an interesting 'graph on the relative costs of operating in urban and rural areas. This showed that over a 140,000-mile vehicle life maintenance costs for a town vehicle were £1200 more expensive than for a rural one. As far as gear ratios were concerned, Mr Farley said that Tate and Lyle's practice was to ensure that all its vehicles could restart on a 1 in 6 hill. Linked to this was the maximum speed and the number of gear steps necessary to attain it.

Having considered what type of vehicle was required it was necessary to make a thorough review of the specifications of all the suitable available models. This could be accomplished with the help of information published in the trade press. Once the field had been narrowed by this process a physical test could be undertaken. This involved borrowing a manufacturer's demonstration vehicle and operating it under an operator's own conditions. Thus an actual fuel consumption could be established. A Tate and Lyle study had shown that, over 50,000 miles, there was a difference in fuel cost of £215 between three competitive types of vehicle.

It was often helpful to evolve a standard test to evaluate a number of good commercial vehicles. A typical test might consist of four parts: an engineer's test, a road test, a static test and a reliability test. Tate and Lyle road tests followed a five-day programme which included local work, long journey work laden and unladen, and a special engineering test which used a standard route. The completion of this procedure should narrow the choice to one or two possibilities and a final selection of chassis could be made. But before purchase a review of components, cab and body specification should be made. Only when this had been done could the final stage of the selection process — implementation — take place.

Mr Farley concluded his paper by saying that the effort, discipline and costs which his selection system entailed were all worthwhile. His final advice on the subject was: "A conservative approach to change may not bring spectacular success but equally and more important it will not tempt disaster. If a single factor had to be chosen to achieve a criterion for success it would be 'reliability'."

The first questioner probably voiced the opinions of many when he asked how many operators had the facilities, staff and money to carry out the selection exercise Mr Farley had outlined.

Mr Farley was quick to point out that very little expense was involved; if there was sufficient will to institute such a system then there would be little difficulty. Essentially, all that was required from resources was an analysis of the results of maintenance.