'To see work lost through unfair and illegal operation is unacceptable'

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

itI very much welcome any

clampdown on Vehicle Excise Duty dodgers as this evasion has been the thorn in the side of many legal hauliers for a long time.

However, I was surprised by comments made by South Eastern Licensing Authority Brigadier Michael Turner who recently stated he takes a tough attitude towards tax dodging. Not long ago I telephoned his office to report an operator who was — and still is — running his vehicles without tax. I was told by two people there: "It's none of our business" and "It's nothing to do with us, it's a DVLA problem".

This wasn't quite the response I had expected from supposedly such a "tough" Licensing Authority, and I have since learnt that this was by no means a solitary incident. Many other operators I know have had similar experiences with Licensing Authorities and have simply given up in sheer frustration.

Legal operators also face another problem — the substantial increase in companies declaring bankruptcy only to recommence trading under a different name and with a new Operator's Licence. While I know this is a difficult task for the Licensing Authorities to tackle, it must be given top priority before the honest operator disappears completely.

The other issue that needs tackling is the ever-decreasing rate chargeable to customers. Many hauliers are running vehicles at lower charges than 10 years ago, despite a large increase in vehicle, fuel and general running costs.

A large proportion of the blame must be placed on some of the large manufacturers which have sold their vehicles to their own driver-employees. At the outset this must have seemed a novel and exciting prospect for the new owner-drivers: in reality it has brought a cut in haulage rates.

When contracts get tight the driver, having already committed himself to vehicle finance, finds himself with no alternative but to accept. Therefore many rates paid by the largest companies in the country verge on the suicidal.

But so-called "clearing houses" also take on large contracts at unrealistic rates. It would appear that provided their own cut is sufficient, they are not concerned at the pittance remaining for the haulier who actually does the job.

With a decent rate hauliers would be in a better position to tax, insure and maintain their vehicles to a high standard, and also pay their drivers the wage they richly deserve. It would also alleviate the pressure on some hauliers who evidently feel that the only way to stay in business is to overload, work over their hours and commit speeding offences.

No haulier should be afraid of fair competition, but to see rates cut and work lost through unfair and illegal operation is unacceptable. So come on, Brigadier Turner and you other Licensing Authorities — take heed, and the next time a haulier telephones with a complaint, let's see some action before it's too late. /

V ou British started civilisation — and 1 that's when you stopped," mutters Olaf Karlsen, a Danish haulier now living in Grimsby.

He is disgusted at the way British haulage companies are taking longer and longer to pay drivers. "The companies are all the bloody same," he snaps. He and fellow owner-driver Tommy Whitehead say they have both been stung by delayed payments for haulage jobs.

Karlsen has now gone into liquidation after numerous bounced cheques for haulage work. Whitehead, who operates from Grimsby as Traction International, was recently brought to the brink of bankruptcy by slow payments — but then he took the law into his own hands.

He had been working for Chenmark International, a haulage company based in Immingham, since mid-March. By late June it had not paid him, so he decided to force its hand. He planned to impound one of Chenmark's loads and hold on to it until his fees came through. The scheme almost landed him in prison.

Whitehead set up Traction International in 1988 with an Operator's Licence for three vehicles and four trailers. The company has been delivering to Spain. Portugal and Eastern Europe.

Whitehead was getting desperate for money, as he owed £2,300 for diesel and tyres to another haulage company he had been working for up until March. His financial problems are underlined by the tractor unit he now runs — a road-worn V-reg Scania 141.

"There it is," he says with a sigh as he gestures to his venerable rig. "This is what I'm reduced to driving."

Earlier this year his former employers impounded his trailer and threatened court action to reclaim their money. Confident that his work for Chenmark would cover this, Whitehead had promised that he would clear this debt within three months — but when the deadline came Chenmark still had not paid him.

The company now owed him more than £10,000, less about £3,000 for running costs. Whitehead says he started work on the understanding that he would be paid monthly, on the issue of an invoice. He says that he thought the rate would work out at around 75p per mile — "a liveable rate", for tractor-only work.

During March Whitehead Moved one-and-a-half loads; by the end of April, he still had not received confirmation of the rates for these jobs. He asked for confirmation notes to be written and the company assured him that this would be done.

He didn't receive any paperwork until June, by which time he was losing his patience. In mid-June he asked Chenmark for money on account to cover his bills and was assured that £2,000 would he

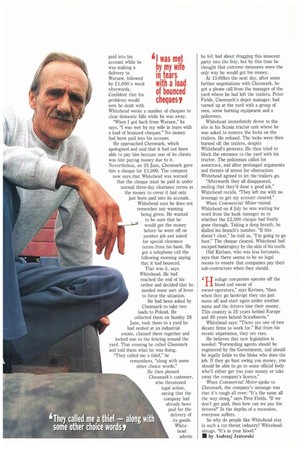

61 was met by my wife in tears with a load of bounced cheques,

paid into his account while he was making a delivery to Warsaw, followed by £1,000 a week afterwards. Confident that his problems would now be dealt with Whitehead wrote a number of cheques to clear domestic bills while he was away.

"When I got back from Warsaw," he says, "I was met by my wife in tears with a load of bounced cheques." No money had been paid into his account.

He approached Chenmark, which apologised and said that it had not been able to pay him because one of its clients was late paying money due to it. Nevertheless, on 25 June, Chenmark gave him a cheque for £2,000. The company now says that Whitehead was warned that the cheque must be paid in under normal three-day clearance terms as the money to cover it had only just been paid into its account.

Whitehead says he does not remember any warning being given. He wanted to be sure that he would get the money before he went off on another job and asked for special clearance terms from his bank. He got a telephone call the following morning saying that it had bounced.

That was it, says Whitehead. He had reached the end of his tether and decided that he needed some sort of lever to force the situation, He had been asked by Chenmark to take two loads to Poland. He collected them on Sunday 28 June, took them to a yard he had rented at an industrial estate, chained them together and locked one to the fencing around the yard. That evening he called Chenmark and told them what he was doing. "They called me a thief," he remembers, "along with some other choice words."

He then phoned Chenmark's customer, who threatened legal action, saying that the company had

already been paid for the delivery of its goods. White

head admits he felt bad about dragging this innocent party into the fray, but by this time he thought that extreme measures were the only way he would get his money.

At 15:00hrs the next day, after some further negotiations with Chenmark, he got a phone call from the manager of the yard where he had left the trailers. Peter Fields, Chenrnark's depot manager, had turned up at the yard with a group of men, some burning equipment and a policeman.

Whitehead immediately drove to the site in his Scania tractor unit where he was asked to remove the locks on the trailers. He refused. The locks were then burned off the trailers, despite Whitehead's protests. He then tried to block the entrance to the yard with his tractor. The policeman called for assistance, and after prolonged arguments and threats of arrest for obstruction Whitehead agreed to let the trailers go.

"Afterwards they all disappeared, smiling that they'd done a good job," Whitehead recalls. "They left me with no leverage to get my account cleared."

When Commercial Motor visited Whitehead on 8 July he was waiting for word from the bank manager as to whether the £2,000 cheque had finally gone through. Taking a deep breath, he dialled his branch's number. "If this doesn't clear," he told us, "I'm going to go bust." The cheque cleared. Whitehead had escaped bankruptcy by the skin of his teeth.

Olaf Karlsen, who was less fortunate, says that there seems to be no legal means to ensure that companies pay their sub-contractors when they should.

aulage companies operate off the

11 blood and sweat of owner-operators," says Karlsen, "then when they go bankrupt they can just move off and start again under another name and the drivers lose their money. This country is 25 years behind Europe and 40 years behind Scandinavia."

Whitehead says: "There are one of two decent firms to work for." But from his recent experience, they are rare.

He believes that new legislation is needed: "Forwarding agents should be registered by the Government, and should be legally liable to the bloke who does the job. If they go bust owing you money, you should be able to go to some official body who'll either get you your money or take away the company's licence."

When Commercial Motor spoke to Chenmark, the company's message was that it's tough all over: "It's the same all the way along," says Pete Fields. "If we don't get paid, then how can we pay the drivers?" In the depths of a recession, everyone suffers.

So why do people like Whitehead stay in such a cut-throat industry? Whitehead shrugs. "It's in your blood."

• by Andrzej Jeziorski