Distribution trends: The outlook

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by John Darker maim

INFLATIONARY pressures on the business life of the community may be expected to have a quite drastic effect on distribution. No one can predict the length of the current recession but distribution managers seem likely to be faced by twin pressures from general management: to cut costs and to improve efficiency. And this at a time of rapidly rising wages, transport and warehousing costs.

Cash-flow problems, in conjunction with the high cost and possible scarcity of fuel, may compel major manufacturers and professional distributors to review the extent of their depot networks. Improved efficiency, with smaller throughputs of goods, may permit some depots to be sold to bring in much needed cash transfusions. But that solution could involve higher vehicle mileages unless service standards are markedly worsened.

Vehicle suitability

The number and suitability of vehicles operated and their efficient deployment will need to be constantly reviewed. The distribution networks of go-it-alone manufacturers will be maintained with increasing difficulty. The compatible products of different manufacturers may be streamed together in multi-company distributive activities, with combined use of existing depot facilities.

The specialist distribution companies, both independent and State owned, have been striving to increase their share of the distribution market. If the firms concerned can win traffic from companies now undertaking the whole of their own distribution, this will benefit the professionals. But half-empty warehouses and wastefully used vehicles could encourage costly competition between professional distributors.

Already, it is apparent that there is intense competition for the distribution of the most readily handleable products, ie the right weight, volume, carton-size, throughput, conveniently picked up and delivered with the minimum of delay. Who can wonder at this? It is the transport operator's job to know the most profitable traffic to look for. Nonspecialist 'general hauliers' are akin to an over-populated gold-fish bowl.

There is a fast-growing trend for the larger professional operators — BRS and Ryder come to mind — to offer quite elaborate consultancy services. Ryder Truck Rentals, in America, are regularly asked to evaluate the merits of particular distribution systems, no doubt with a view to making out a good case for the extensive use of contract hire fleets. BRS, in this country, is currently working on around 40 major inquiries for clients, or prospective clients, with distribution headaches.

A recent , computer programme developed by Roger Trigell, the group consultancy manager of BRS, called 'Sizing the delivery fleet', gives the answer to the $64 question for distributors with local delivery problems: How many vehicles do I need and what size should they be? The programme enables an accurate answer to be worked out and a number of different assumptions, such as the impact of seasonality, and different sizes of vehicles, can be evaluated. This programme can be purchased for £4,000, or leased.

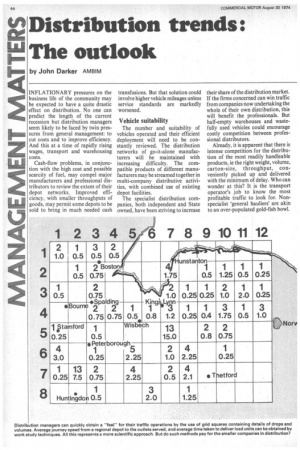

It would be interesting to know how many people earning a living from distribution are aware of the scientific method of approach which is second nature to many young practising distribution managers. I suspect that outside the top echelons of distribution and transport management, numbering perhaps a few hundred people, the idea of plotting what is actually done in distribution on grid squares on a map, and using the supporting data — total volume of goods to be delivered, the number of separate deliveries to be made, fixed times for deliveries, unloading time per unit of commodity and average vehicle operating speeds for the various zones through which the vehicle passes to its delivery point — would be totally foreign. But this logical approach must increasingly dominate the larger distribution activities.

Even if the idea of using computers is anathema, large-scale distribution cannot be sensibly planned without the use of work study techniques — another scientific approach — and comprehensive mathematical calculations to test the viability of supporting warehousing and trans port operations.

Unknown costs

It is probably true to say that 90 per cent of this country's distribution activities are at the penny-farthing stage of development in comparison with what is possible given the willpower to bring them up to date.

Costs are seldom known, the hardware in terms of vehicles and premises is often misconceived or downright primitive. And yet, accepting these stern strictures, the total system works to most people's satisfaction. As more highly trained people examine the weaker, more wasteful sectors, the gap between the best and worst practice will narrow.

Empty mileage

Increasing road congestion, the need to make the best use of available road space and fuel conservation needs may provoke criticisms from the environmentalists, even some who work in transport. to review the extent of empty mileage. The criteria which have made it 'economic' hitherto to deliver a full load of goods on a 100-mile or more journey, with an empty return trip, may not continue to be valid for much longer.

Any marked change in operating patterns for the 150-mile radius work in which road haulage excels in Britain will not be easily accomplished because the patterns concerned have been built into the coststructures of so many manufacturing and distributive organizations.

Containerization, because of the continuing huge world investment, will play an increasing role in internal distribution. Containerization reflects the application of the mass production principle, for the first time, to transport operations — as opposed to vehicles. It also lends itself to the economists' division of labour' concept hence new motor car plants in Korea or whatever.

The vulnerability of massive flows of containers to strike action or traffic thrombosis is a risk cheerfully faced by the promoters of the system, though the road transport operators might have preferred the simpler unit-load concept, which is ideal for lorry/ ship transfers and largely avoids the inevitable handling delays at large container ports.

Ports strategy

The choice of sites for new port or coastal terminal or manufacturing plant must tend to focus the regional loyalties of road hauliers and other operators with business interests at stake. The 'national interest' is a nebulous concept to many people and particularly to an operator whose business could be ruined if port A is preferred to port B in a national ports strategy. If ever the Chartered Institute of Transport has to pronounce on the national merits of major investment projects some regional members' loyalties may be strained.

The virtual identity of interests between large own-account operators and the major professionals offering tailor-made distribution systems — with or without contract hire facilities — is a remarkable feature of an industry which used to regard the two elements as distinctly different animals. The fact that some major manufacturers can undertake some of their own distribution while hiving off convenient sectors to the profes sional operators — and requiring both operations to conform with precisely engineered service and opera tional standards, again calls in question the utility of separate trade associations.