COST RECORDING

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

MADE EASY

I HAVE had an astonishing number of requests of late for 1 HAVE regarding a simple cost-recording system. These inquiries have come from small operators, all of whom, it is clear, have had no experience of keeping accurate records of cost. To all of them I have recommended a disconnected series of articles which I wrote last year. Unfortunately. it would appear that most of the inquirers are newly returned to civilian life from the Services and have not been getting their copies of "The Commercial Motor." I am. therefore, going to rewrite that series from the angle of the man who either has not kept cost records or is not satisfied with the accounts he has been keeping.

The principal objective is to know immediately what are the haulier's actual costs, making allowance for all future contingencies, also providing for his lack of knowledge of costs, and assuming that he wants that information as a basis for assessing rates.

The items of current expenditure with which the operator becomes immediately acquainted are only three, namely, fuel, lubricating oil, and wages. There are others which he can recall and note, such as taxation, cost of insurance, and garage rent. In addition to those three there is another item—interest'on first cost There are two items of major importance of which he has no knowledge and about which he will not know anything for many months. I refer to his probable expenditure on tyres and maintenance, and as it is necessary in this assessment of costs to make provision for future expenditure on those two items, I will estimate for them.

The reason for making estimates is that the operator may not know for six months what is going to be his expenditure for tyres, and he may not know for two or three years what he is going to spend on maintaining his vehicle. These items must be covered during those waiting periods by estimates.

At the same time he must not overlook the necessity of collecting actual figures for cost, so that he can build up, out of his own experience, figures which will replace preliminary estimates and put his costing on a more certain foundation.

In the system which I am going to describe there is provision for the estimated cost of tyres, maintenance, and the actual cost, and at the close of this series I shall indicate how to amend the one to bring it more closely into line with the other.

To make the matter more realistic, I am going to assume that 1 am planning this system of cost recording for an operator owning a small fleet of vehicles comprising one 10-tonner, two 8-tonners, and four 6-tonners. That is a total of SO tons of pay-load, a figure which I shall need to use later when dealing with certain items of expenditure and their allocatiat amongst the vehicles of the fleet.

After that preamble. I come now to establishing four fundamentals of this simple system of cost recording. First, simplicity. The system is designed so as to call for the minimum of clerical work. Secondly, notwithstanding the need for simplicity, I am firm in the conviction that it is necessary to record the cost of each vehicle separately. This is not difficult, even with comparatively large fleets. It becomes cumbersome only in respect of concerns owning upwards of 100 vehicles, and then it is usual to group the machines so that all of one particular make, type, and load capacity are dealt with collectively.

Thirdly, it is necessary to discriminate carefully between vehicle operating costs and other expenditure which may not be debited to the vehicles It is not difficult—and in ordelto achieve that object it is wise—to adhere to the arrangement of cost items which has been standardized in "The Commercial Motor" Tables of Operating Costs.

According to that publication, there are 10 items of cost involved in operating a commercial vehicle. They are: Fuel, oil, tyres, maintenance, and depreciation. These are called running costs, as they rise or fall according to the number of miles that the vehicle covers. Then come wages, Road Fund tax, vehicle insurance, garage rent, and interest on capital outlay. These are called standing charges, because, broadly speaking, they remain constant in amount each week. Of these five, wages fluctuate and provision is made for that variation in this system of cost recording. Grouped with the item, wages, are the payments which have to be made on account of National Health and Unemployment Insurance, and insurance under the Workmen's Compensation Act.

Those 10 itelps comprise all that may be debited as vehicle operating costs. They may be subdivided, as. for example, maintenance may be divided into materials and labour, but the basic principle remains unaltered, and any expenditure incurred which clearly cannot be entered under one of those 10 headings is not an item of vehicle operating cost—it is what I call an establishment cost, and what some people call an overhead cost. In the course of this series I shall deal in meticulous detail with establishment costs.

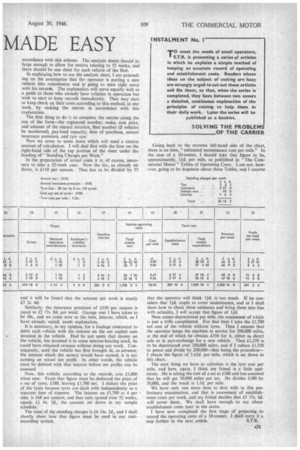

The method I recommend is exemplified in the accompanying Table, which is a sample analysis cost sheet. There are certain typical figures of cost entered into the analysis sheet, enabling me to explain how to use it. Many old readers of these articles will recognize the method as having been explained previously. "The Commercial Motor" does not provide these forms. Reader: who wish to make use of the system are recommended to have suitable analysis sheets printed by a local stationet, or to purchase suitable ruled forms without headings which they fill in themselves in accordance with this scheme. The analysis sheets should he large enough to allow for entries relating to 52 weeks, and there should be one sheet for each vehicle of the fleet.

In explaining how to use the analysis sheet, I am proceeding on the assumption that the operator is putting a new vehicle into commission and is' going to start right away with his records. The explanation will serve equally well as a guide to those who already have vehicles in operation but wish to start to keep records immediately. They may start to keep check on their costs according to this method, at any week, by making the entries in accordance with this explanation.

The first thing to do ij to complete the entries along the top of the form—the registered number, make, cost price, and amount of the annual taxation, fleet number (if vehicles be numbered), pay-load capacity, date of purchase, annual insurance premium, and tyre size.

Now we come to some items which will need a certain amount of calculation. I will deal first with the four on the right-hand side of the top portion of the sheet under the heading of " Standing Charges per Week."

In the preparation of actual costs it is, of course, necessary to take a 52-week year. Now the tax, as already set down, is £110 per annum. That has to be divided by 51 and it will be founi that the amount per week is nearly £2 2s. 4d.

Similarly, the insurance premium of £150 per annum is equal to £2 17s. 8d. per week: Garage rent 1 have taken to be 10s., and we come now to the item, interest, which, as 1 have already stated, needs explanation.

It is necessary, in my opinion, for a haulage contractor to debit each vehicle with the interest on the net capital sum • invested in the vehicle. Had he not spent that money on the vehicle, but invested it in some interest-bearing stock, he could have obtained revenue without doing any work. Consequently, until the vehicle has first brought in, as revenue, the interest which the money would have earned, it is not • earning an actual net profit. In other words, the vehicle must be debited with that interest before net profits can be assessed.

Now, this vehicle, according to the records, cost £1,880. when new. From that figure must be deducted the price of a set of tyres, £180, leaving £1,700 net. 1 deduct the price of the tyres because tyres are dealt with independently as a • separate item of expense. The interest on 11,700 at 4 per cent. is £68 per annum, and that sum, spread over 52 weeks, equals £1 6s. 2d., the amount set down in my sample schedule.

The total of the standing charges is £6 16s. 2d., and I shall shortly show how that figure must be used in our costrecording system. that the operator wi I think lid. is 'too much. If he considers that lid. ought to cover maintenance, and as I shall show how to check these estimates and bring them into line with actuality, I will accept that figure of lid.

Next comes depreciation per mile, the assessment of which is just a trifle complicated. For that item I take the £1,700 net cost of the vehicle without tyres. Then I assume that the operator keeps the machine in service for 200,000 miles, at the end of which he obtains £350 for it, either as direct sale or in part-exchange for a new vehicle. Thus £1,350 is to be depreciated over 200,000 miles, and if 1 reduce £1,350 to pence and divide by 200,000—that being the procedure1 obtain the figure of 1.62d. per mile, which is set down in this chart.

The next thing we have to calculate is the tyre cost per mile, and here, again, 1 think my friend is a little optimistic. .He is taking the cost of a set at £180 and has assumed that he will get 30,000 miles per set. He divides £180 by 30,000, and the result is 1.5d. per mile. We have only one more item to deal with in this pteliminary examination, and that is assessment of establishmeat costs per week, and my friend decides that £3 17s. 6d. will cover them. We shall have enough to say about establishment costs later in the series.

1 have now completed the first stage of preparing to record the operating costs of a 10-tonner. I shall carry it a

step farther in the next article. S.T.R.