A Chip Off the Old Bloc

Page 50

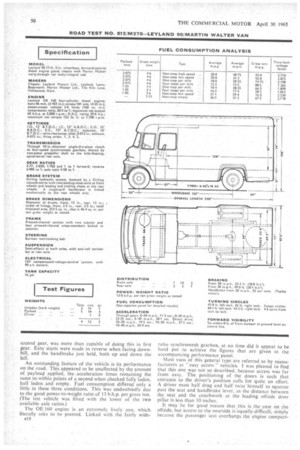

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By R. D. Cater

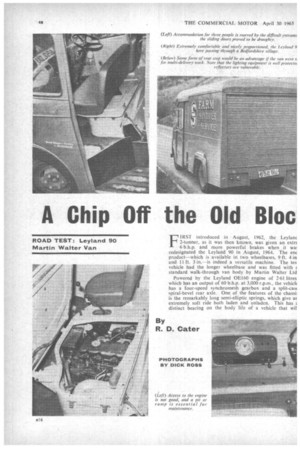

FMST introduced in August, 1962, the Leylanc 2-tormer, as it was then known, was given an extrE 6 b.h.p. and more powerful brakes when it wai redesignated the Leyland 90 in August, 1964. The enc

product which is available in two wheelbases, 9 ft. 4 in and lift. 3 in.—is indeed a versatile machine. The tes vehicle had the longer wheelbase and was fitted with 1 standard walk-through van body by Martin Walter Ltd

Powered by the Leyland 0E160 engine of 2-61,litres which has an output of 60 b.h.p, at 3,000 r.p.m., the vehicli has a four-speed synchromesh gearbox and a split-cam spiral-bevel rear axle. One of the features of the chassii is the remarkably long semi-elliptic springs, which give at extremely soft ride both laden and unladen. This has E distinct bearing on the body life of a vehicle that wil

inevitably spend a large proportion of its time running either halt-laden or empty.

This Leyland, which can fill almost .every need in the 90 cwt. gross weight range, is available as a chassis/cab or chassis/scuttle (for integral cab), or as a bare chassis. The " 90 has a set-back engine and incorporates a lowmounted radiator and crankshaft-mounted fan, A torsional anti-roll bar is included in the rear suspension.

A pronounced feel of thoroughbred is evident when driving the Leyland 90, which is mainly due to the lack of flap in the gear and handbrake levers—a characteristic that is so often prominent in lightweight vehicles. The steering, also, is positive and accurate, adding to the general impression of tautness. These points, coupled with excellent seats, make it a vehicle in which a driver would be equally at home on round-the-houses delivery work or on long-distance trunk work. One thing spoils the general comfort of the machine, however—noise. A decidedly harsh " cackle " is produced when full throttle is applied, although it must be admitted That this is only necessary when climbing or accelerating. Once on the open road, only the slightest touch of throttle is required to keep the vehicle moving briskly along at speeds close to its makimum.

This Leyland served to prove once again that wheel skidding is not necessary in order to produce good' braking figures. Although vivid black marks and a lot of smoke look impressive it is, after all, the end result that is important. With a complete absence of wheel-locking, the deceleration figures obtained with this vehicle were good at 18.8 ft. per sec? from 20 m.p.h. and 20.1 ft. per sec.' from 30 m.p.h. But there proved to be a snag, This was excessive brake fade, a drop to the tune of 46 per cent from 20 m.p.h. becoming apparent when our usual fade test was carried out. Recuperation of the brakes was, however, fairly good.

The fade test was carried out on Bison Hill in the usual manner—coasting downhill against the brakes at 20 m.p.h., then engaging top gear once the speed dropped below 20, and continuing to drive at 20 m.p.h. against the brakes. At the end, a full-pressure stop produced a meter reading of only 33 per cent. The total length of this test is 0-75 miles, and it is an extremely severe one, the like of which a vehicle would seldom encounter inactual service.

. Because the fade had been so bad, to check this point ran the vehicle for a mile at 30 m.p.h. and then carried out a second full-pressure stop. A reading of 52 per cent on the Tapley meter was obtained—an improvement of 19 per cent over the fade test reading obtained on the first test.

Figures obtained during the hill clirrib. which again was carried out on Bison Hill (maximum gradient I in 6.5, overall gradient 1 in 10) were good. Climbing from bottom to top in a total time of 3 min. 15.2 sec., it was necessary to drop only one ratio. from third to second, for a period of I min. 12.8 sec., when the minimum speed recorded was 12 m.p.h. There was 'n'o appreciable increase in coolant temperature noticeable When the summit was reached. The ambient temperature at the time was 11°C (52°F). The excellent synchromesh gearbox enabled •a snappy change to be made from second to third gear where the gradient decreases slightly -near the top, when the road -speed reached 16 m.p.h Once the third ratio had been engaged. the Leyland quickly picked up speed and the summit was reached at 22 m.p.h.

Stop and restart tests on the steepest part of this hill showed that the vehicle, whilst being-unable to move off in B17 second gear, was more than capable of doing this in first gear. Easy starts were made in reverse when facing downhill, and the handbrake just held, both up and down the hill.

An outstanding feature of the vehicle is its performance on the road. This appeared to be unaffected by the amount of payload applied, the. acceleration times remaining the same to within points of a second when checked fully laden, half laden and empty. Fuel consumption differed only a little in these three conditions. This was undoubtedly due to the good power-to-weight ratio of 13 b.h.p. per gross ton. (The test vehicle was fitted with the lower of the two available axle ratios.) The OE 160 engine is an extremely lively one, which literally asks to be pressed. Linked with the fairly wideal 8 ratio synchromesh gearbox, at no time did it appear to be hard put to achieve the figures that are given in the accompanying performance panel.

Most vans of this general type are referred to by manufacturers as easy access vehicles. I was pleased to find that this one was not so described, because access was far from easy. The positioning of the doors is such that entrance to the driver's position calls for quite an effort. A driver must half drag and half twist himself to squeeze past the seat and handbrake lever, as the distance between the seat and the coachwork at the leading offside door pillar is less than 10 inches.

It may be for good reason that this is the case on the offside, hut 'access to the nearside is-equally difficult, simply because the passenger seat overhangs the engine compart ment cover. By removing the overhung portion, entrance from this side would be greatly simplified at the cost of only a few inches of passenger seat which, being large enough to seat two large men comfortably, will seldom be used to its full extent.

Behind the seats is a gangway allowing access to the body. This, coupled with the well-type steps, certainly makes the entrance into the main body simple without the need to open the rear shutter. If the vehicle were destined to .be used as a mobile shop, then this point would rate as more important than access to the driving seat.

The vehicle tested had been fitted for vending assorted seeds around farms in Staffordshire and inside the body were a number of compartmented shelves which had been fitted by the customer. A bulkhead had also been fitted to separate the body from the driving compartment, access being through a sliding door. Throughout the test this door insisted on jumping off its runners, creating a shocking noise and presenting quite a problem to put back. This was not a Martin Walter fitting, it having been added by the customer.

The 510 Cu. ft. body of the test vehicle was constructed on a metal' framework; side panels were of 20 s.w.g. steel with all joints sealed and covered with alloy mouldings. l'he roof was a one-piece resin-bonded glass-fibre moulding incorporating a translucent panel which provided interior light. A in.-thick, tongued and grooved floor was fitted with rectangular steel wheelboxes. Swaged strainers had been fitted longitudinally in the insides, giving protection to the panels and providing an unobstructed line. The rear entrance was 5 ft. high by 5 ft. 7 in. wide, and was closed by a Nyloy roller shutter. A loading height of 31 in. proved to be very acceptable when I unloaded the vehicle to conduct the half laden and unladen tests, which involved lifting the ballast.

Falling below the standard of the vehicle in general, two of the accessories—the mirrors and the screenwipers---gave cause for criticism. The mirrors, as is often the case on light vehicles, were very poor. They were small and looked flimsy. To move them and later to reset them (to avoid damage in a confined area, for instance) would be a major job_ As for the wipers, they were of ample dimensions but the offside blade could not completely wipe its side of the screen. The radius of the glass was so acute at the corner that the blade could not follow the contours, leaving a large, uncleaned portion in bad weather. Coupled with the width of the fairly thick corner-pillars, this left a strip about II in. wide which was blind in dirty conditions.

Apart from this, however, the visibility from the driving seat was excellent, the inclusion of screenwasfiers having proved a decided advantage on the first day of the test. These, I suggest, should now be a compulsory fitting on all vehicles and not, as in most cases, an optional extra.

A problem which arose during the test was that when the vehicle was placed in a position that created a twist in the chassis (for example, with the offside front and nearside rear raised) the throttle automatically opened about a third. This nearly caused me to collide with a farm gateway that I was reversing into and pointed to a considerable whip in the frame.

One point about the outside of the body seemed unfortunate—the rear wings, for no apparent practical reason, protruded several inches beyond the rest of the body. My personal opinion is that they did not add to the appearance of the vehicle, but they were vulnerable and increased the overall width; in some circumstances this could prove embarrassing to a driver trying to get into a narrow entrance.

Access to Engine The initial access to the engine is by lifting the passenger seat. But, without taking off the rear panel of the engine cover, access would prove somewhat difficult, and to remove this cover it is necessary to undo a number of wood screws which hold the cover to the floor. Even when this was done it seemed to me that quite a number of jobs would prove difficult to execute and might therefore be skimped. I would have preferred to see the seat-box arranged in such a way that it could be removed as a whok —held down, perhaps, by half a dozen A in. bolts through a reinforced flange picking up on trapped nuts in the floor.

As tested. the Leyland 90 with Martin Walter body cost £1,280, which is made up as follows: cl,assis, £885; heater,' demister, £17 10s.; screenwasher, £3; delivery; £4 15s.; body complete with glass-fibre roof and rear roller-shutter (but excluding the shelving in the test vehicle), £370. These are retail prices.