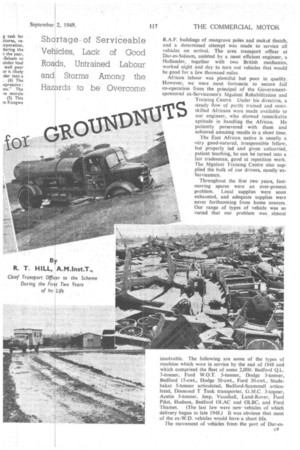

By R. T. HILL, A.M.Inst.T., Chief Transport Officer to the

Page 47

Page 46

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Scheme During the First Two Years of Its Life MUCH has been written about the Groundnuts Scheme, of which most has been ill-informed. One thing is certain, and that is the whole project was a brilliant conception, and full tribute should be paid to Mr. Frank Samuel, of the United Africa Company, in whose brain germinated the idea of converting vast tracts of bush and waste lands of Africa into productive agricultural areas.

From the beginning, the United Africa Co., which as managing agent undertook the onerous task of pioneering the scheme, laboured under great handicaps. No time was given for detailed planning, and no new equipment was available in a post-war world, and yet the company was asked to conduct one of the largest agricultural and social experiments that the world has seen, as a "Mulberry Operation," but without war-time organization behind it

A "Great Undertaking" The problems which beset the small but enthusiastic band of Britons which constituted the advance party under the leadership of Mr. D. L. Martin, would make a story in itself; the intention of this article, however, is to give some idea of the important part played by road transport, and of the problems which faced the transport people who shared in this great undertaking.

It was obvious from the outset that large numbers of motor vehicles, particularly load carriers, would be required for (a) port-clearance work, (b) for distributing vast quantities of supplies of all kinds to the contractors' units and the agricultural units in the field, and (c) for long-distance road convoys which would supplement the inadequate or non-existent rail trunk services in Ta nga nyika.

No one knows better than the commercial vehicle operator how difficult it was to secure new vehicles in 1947; although the managing agency was prepared to place large orders for vehicles, the earliest possible delivery was 18 months. Speed was of paramount importance. The war-disposal dumps of Western Europe, the Mediterranean countries and the Middle East supplied the only answer, and the managing agency's buyers made" blanket" purchases and arranged shipment to Dar-es-Salaam.

Some 200 more-or-less serviceable Dodge and Fordc8 son 3-tonner6 were "picked up" from the Kenya Disposals Board, and these were some of the earliest deliveries to the first selected area at Kongwa. Foodstuffs and domestic stores, bedding, furniture, technical • stores, and so on, all urgently required at Kongwa, comprised the loads for the first convoys, which had to traverse 600 miles of dirt road to reach their destination. Road travel in East Africa is no picnic. Long stretches of black cotton soil become morasses during the rains, and bridges are always doubtful. Any river beds or " dongas " become raging torrents after a comparatively short storm, and the African driver is by no means as reliable as his British counterpart.

Nevertheless, the convoys did get through with comparatively few casualties, thanks mainly to two locally recruited convoy commanders.

Meanwhile, April, 1947, saw the arrival of the first cargoes at the port of Dar-es-Salaam, and thereafter there was a fairly steady flow of ex-W.D. vehicles from the Middle East and Europe. Their condition left much to be desired, as most of them had been standing in open dumps and subjected to all weathers. Many were minus essential components due to theft; electrical and petrol faults became a nightmare.

A transport workshop was established in some disused R.A.F. buildings of mangrove poles and mak ut thatch, and a determined attempt was made to service all vehicles on arrival. The area transport officer at Dar-es-Salaam, assisted by a most efficient engineer, a Hollander, together with two British mechanics, worked night and day to turn out vehicles that would be good for a few thousand miles.

African labour was plentiful but poor in quality. However, we were most fortunate to secure full co-operation from the principal of the Governmentsponsored ex-Servicemen's tvlgulani Rehabilitation and Training Centre. Under his direction, a steady flow of partly trained and semiskilled Africans were made available to our engineer, who showed remarkable aptitude in handling the African. He patiently persevered with them and achieved amazing results in a short time.

The East African native is usually a very good-natured, irresponsible fellow, but properly led and given unhurried, patient teaching, he can be turned into a fair tradesman, good at repetition work. The Mgulani Training Centre also supplied the bulk of our drivers, mostly exServicemen.

Throughout the first two years, fastmoving spares were an ever-present problem. Local supplies were soon exhausted, and adequate supplies were never forthcoming from home sources. Our range of types of vehicle was so varied that our problem was almost insolvable. The following are some of the types of machine which were in service by the end of 1948 and which comprised the fleet of some 2,000: Bedford Q.L. 3-tonner, Ford W.O.T. .3-tonner, Dodge 3-tonner, Bedford 15-cwt., Dodge 30-cwt., Ford 30-cwt., Studebaker 5-tonner articulated, Bedford-Sea mrnell articulated, Diamond T Tank transporter, G.M.C. 3-topner, Austin 3-tonner, Jeep, Vauxhall, Land-Rover, Ford Pilot, Hudson, Bedford OLAC and OLBC, and Ford Thames. (The last few were new vehicles of which delivery began in late 1948.) it was obvious that most of the ex-W.D. vehicles would have a short life.

The movement of vehicles from the port of Dar-esc9 Salaam to the operational area at Kongwa presented another problem A 'road does exist, running parallel with the east-to-west single-track railway for about 150 miles, the total distance being approximately 350 miles, but for four months in the year it is impassable due to black cotton soil, flooded rivers, etc.

The railway was already stretched to capacity, handling heavy tractors and plant, and there was an acute shortage of flat trucks. Road convoys had to be attempted and the first one, consisting of some 20 load carriers loaded with essential stores, and some Jeeps, succeeded in completing the trip in June, 1947.

The Ferry Boat Capsized Thereafter, convoys operated regularly every 10 days or so, except during the rainy season. The crossing of the Ruvu River, about 60 miles east of Dar-es-Salaam, was in itself a major operation; each vehicle had to be ferried separately over the fast-flowing river on a manpowered cable-operated ferry boat, which threatened to capsize every time it bore weight. Capsize it did, eventually, and remained under water for three months until an overworked public work's department engineer could salvage it.

At Kongwa itself, where land-clearing operations began with some intensity in June, 1947, an M.T. poel was established under the most primitive conditions. Its functions were manifold, Technical and domestic stores of every description were arriving at a temporary railhead some 18 miles from Kongwa; the railway branch line which was eventually to serve Kongwa, was under construction but well behind schedule, and a road haul over a mere track through the bush was inevitable It was a race against time, too; the road would become impassible once the rains began in November. The contractor's units or land-clearing teams in the bush, busily employed in attempting the clearance of the first 30.000 acres and severely handicapped . owing to the unserviceability of their war-worn tractors, had to be supplied with essential load carriers for hauling fuel, stores and water.

A building programme to house Europeans was under way, and load carriers were required to haul all kinds of building material to the sites. There was never sufflcient personnel transport to ensure rapid movement of engineers, tradesmen and agricultural workers to and from their work.

Shortage of Water

The maintenance of adequate supplies of water for both domestic and industrial use was an ever-present problem. Boreholes for water were sunk, but the supply obtained was saline and unfit for European consumption, and again, a 15-mile road haul had to be instituted to ensure supplies from a mountain spring at Sagara.

The wastage of the second-hand transport was alarming; hwas found well-nigh impossible to keep a reasonable proportion of the mixed fleet serviceable. Spares, tools, and skilled labour were a mere trickle, and could not keep pace with wear and tear. Nevertheless, the work went on and some feats of improvisation were achieved under the most difficult working conditions.

Cannibalization was resorted to; road springs which had a pitifully short life on the corrugated dirt roads were fabricated on site when spring steel was available, metal bodies which survived the hard wear better than wooden ones were removed from serviceable chassis and fitted to "runners," and water tanks were changed over to serviceable, chassis to increase the total water-carrying capacity.

The lack ot suitably trained clerical staff precluded c10 the keeping of .accurate vehicle statistics and records, and, due to the almost complete absence of serviceable speedometers on the vehicles, mileage performance had to be estimated. Nevertheless, a comprehensive system of vehicle-recording was evolved and in operation early,. in 1948. It included daily work tickets (even the African , drivers learned to appreciate the value of his " worki. ticketi " after a few prosecutions had been instituted with resultant prison sentences for misuse and misappropriation of transport); daily and monthly summaries and analyses of vehicle mileage; fuel consumption; hours worked, etc., and a log.file for each vehicle which included registration details, summary of repairs, record of transfer between units, and, in short, a complete history of each vehicle.

It was not until October, 1948, that the position showed signs of improvement, when new Bedford vehicles began to arrive in Kenya. After locally built bodies had been fitted in Nairobi, the complete vehicles were loaded with stores and road-convoyed to Kongwa. Deliveries of Land Rovers also began, and were issued as replacements for worn-out Jeeps.

When the writer left the territory in February of this year, many new vehicles were in service, and the demand was being met, but -there was still a quite inadequate coverage of spares. When will the British manufacturer realize that his reputation overseas depends on "service after sales " and that it is quite useless shipping large quantities of vehicles to a user unless they are accompanied by an adequate stock of fast moving spares?

Two Schemes in Hand

At Urambo, in the Western Province of Tanganyika, also in the Southern Province, groundnut areas were being developed at the same time as the Kongwa development was proceeding; although the momentum was slower, the transport problems were predominant. The rate of unserviceability was high, due to bad roads, lack of spares, and high mileages with worn-out ex-W.D. vehicles. LTrambo has no connecting road to the port of Dar-es-Salaam, consequently all motor vehicles had to be railed to that area.

Four hundred-odd new vehicles were delivered to the Southern Province through the port of Lindi during the latter half of 1948, but it was not possible to issue or deploy them to the best advantage, due to an acute shortage of petrol caused by a lack of suitable shipping on the coast. A150-mile pipe-line, which is under construction from the coast to the agricultural areas, will ultimately solve this problem.

What of the future? The taxpayer is entitled to ask. Late in 1948, a Transport Advisory Committee, consisting of the transport, technical and supply chief executives, was set up to consider all the road transport problems affecting the scherrie, and to advise the management and the board of the Corporation. Workshops properly equipped and manned had passed the drawingboard stage, advice was tendered by the committee on the various types of vehicle which were the most suitable to resist the hard conditions and wear-and-tear of service in a roadless territory, and full use was being made of the available statistical information on performance, etc.

Various methods of handling harvested crops from field to store, and store to railhead, were under active consideration. The board of the Corporation is, however, now committed to a policy of decentralization, and it is doubtful whether it has allowed the Advisory Committee to function as it was intended. There is no doubt that there is still a colossal task ahead, and an enormous amount of leeway to be made up before road transport becomes an efficient servant to the scheme.