The Die is Cast for the Future

Page 96

Page 97

Page 98

Page 101

Page 102

Page 103

Page 107

Page 108

Page 109

Page 160

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By A. J. P. WILDING,

A.M.I. MECH.E

THE heading given to the technical review of chassis exhibits at the 1962 Commercial Motor Show was "The End of An Era ". The end of one era is naturally the start of another—and the 1964 Show most certainly demonstrates this. But in 1962, the main thought in people's minds was the prospect of Britain entering the European Common Market; the hopes for this did not materialize. Instead, we have had the amendments to the Construction and Use Regulations which, in bringing goods vehicle maximum weights and dimensions nearer to the Continental figures, have had very much the same results.

It would be untrue to say that the changes in the Regulations in themselves have had such a large effect on the new designs at Earls Court, because the amendments were confirmed only six weeks or so before the opening date and the new models have obviously had considerably longer time spent on their design than this. Manufacturers have had the proposals to work on for almost two years and no doubt, presuming that these would be little changed (as they turned out to be), laid their plans accordingly.

But whilst the changes in the Regulations make the Show of major importance there are other trends which, even by themselves, would make it the most interesting for many years. The main ones are improved cabs, more powerful engines and better braking and, whilst the last is partly the result of the requirements listed in the C. and U. Regulations the three taken together show that the British manufacturing industry has decided to accept the challenge created by present-day traffic and safety requirements.

In many ways the 1964 Show will be remembered as a "Drivers' Show "—more comfortable surroundings to spend his days in, with heaters becoming a standard fitting rather than an option, better performance to make his life more bearable, with less embarrassment caused by holding up other road users, and better braking to relieve him of the anxiety of stopping in emergencies when he has lessthan-adequate brakes:

It is hard to stipulate which of the three main trends or features at the Show—cabs, engines or brakes—is the

Tiost important; but in view of the current adverse publicity ibout unsafe commercials, probably the wider interest will )e in improved braking. Whilst a considerable improveTient has been made in the brake layouts on all of the lew models at the Show, it is a great pity in my opinion hat only in the case of the new B.M.C. FJ models has his been done on what you could call a voluntary basis.

Except for B.M.C., no manufacturer has provided

a secondary brake system on a vehicle to provide for emergency stopping in the event of failure in the service line unless he has had to do so, This is not an inference that braking systems on British vehicles are generally inadequate or liable to failure; but there is always the possibility, of failure in an air line or hydraulic pipe, or any of the operating components in brake circuits, through damage or faulty maintenance. In these days of higher speeds and

greater traffic congestion, the importance of providing a secondary brake for use in the event of failure cannot be a matter of opinion.

As it is. the vehicle makers introducing goods models suitable for the new Regulations, and therefore requiring a 25 per cent secondary brake, seem to be very uncertain about what exactly is required. The new Regulations could not be more vague on this point. For example, how " separated " has a secondary system got to be? Taken to the logical conclusion, on an air-pressure system there should be separate compressors, reservoirs and valves, lines, operating chambers and even brake units.

And how is the efficiency measured? By actual stopping distance, by Tapley meter, or by the ability of the secondary brake to hold the vehicle on a 25 per cent (1 in 4) gradient? The question of what is required of an artic was also vague but has been resolved by the S.M.M.T. Committee decision only last week to standardize on a three-line system for air-brake outfits: the usual "service and emergency " lines plus an auxiliary line to actuate a secondary system on the semi-trailer at the same time as that on the tractive unit.

It is undoubtedly due to the shortoime since the finalized amendments to the Regulations have been in existence that there is a wide variation between manufacturers in the type of " secondary" braking systems that are fitted. Most makers have gone for actuation of the rear wheel brakes by air pressure as the handbrake is applied and we have triple-, doubleand single-diaphragm chambers to do this work. All could be satisfactory.

The single-diaphragm type as normally used on air brake systems are the least " safe " for, although the separate air-pressure connections from the service brake and from the secondary brake are fed through shuttle valves or similar to make each circuit separate, a fault in the diaphragm renders both systems useless. The dualdiaphragm type overcomes this problem and, by incorporating safety valves in the system, fracture of one of the diaphragms does not allow the escape of air pressure through the second system lines. Triple-diaphragm chambers are safe by themselves in that the third diaphragm is interposed between the service and secondary diaphragms and fracture of either of these does not affect the other system.

I understand that semi-trailer makers are campaigning for the actuation of the front-wheel brakes by the secondary system in the case of tractive units on the grounds that this gives greater stability under wheel-locking conditions. This is certainly true; you may not be able to steer with the front wheels locked but you don't encourage jack-knifing either!

This is, in fact, done on the Foden artics featured at Earls Court, the system on the four-axle outfit being .particularly interesting. There are triple-diaphragm chambers on the tractive unit front axle and semi-trailer forward axle, and combined spring brakes and single-diaphragm chambers at the semi-trailer rearmost axle. There is also a drum-type transmission brake on the tractive unit to complete the coverage.

As pointed out by Mr. H. Perring, of the Ministry of Transport, at The Commercial Motor Fleet Management Conference last week, however, it is far better for an emergency system to apply the brakes at all wheels even though this may only be a proportion of the full braking,

as application at one axle would only lead to wheel locking with detrimental results under conditions of low road adhesion such as with ice or snow.

Two ranges of vehicles which give this feature are the Dennis Maxim and the 11M.C. FJ. On the Dennis, the secondary system is a complete duplication of the service brake with triple-diaphragm chambers at all wheels and two completely separate circuits with reservoirs to each. The B.M.C. FJ has a most interesting brake system incorporating a dual reservoir, providing air by separate circuits to a Clayton Dewandre dual actuator which gives the boost to a Girling tandem master cylinder... From the master cylinder,. the hydraulic circuits to the wheel brakes are separate front and rear and should one of the air circuits to the dual actuator fail partial braking is still provided at all wheels.

Girling has brought out a new range of brake units for the Show and these can be seen on the concern's stand in the gallery. I have heard an interesting suggestion by Girling that, in hydraulic systems with two-leading-shoe units all round instead of having dual circuits for the front-axle and rear-axle brakes, one of the circuits should be to one shoe at each wheel and the second to the other shoes. This would only be applicable where shoe actua

tion was by individual operating cylinders and would give the same result as on the B.M.C. FJ—partial braking on all wheels in the event of failure of one circuit. The drawback would be that on some vehicles the brake drums will not be strong enough to take the uneven loading caused by application of only one shoe in the brake unit.

It is impossible to say it' the changes to the Construction and Use Regulations have been the main reason for manufacturers to turn to bigger engines or if they were planning to do so anyway. Leyland, of course, have not increased the ratings of their units for the higher-weight Freightline range; but the power outputs were already comparatively high by normal standards and the Power-Plus units were possibly designed with increased weights in mind.

At first sight it appears that there has been a general improvement in vehicle power-to-weight ratios; but closer examination reveals that this is not perfectly true in every case. The higher-power units have generally done nothing more than make up for the higher weight for which the vehicles are designed.

The apparent swing to Cummins V power units by users of proprietary engines can only be because no British unit is available to provide adequate power for vehicles running at the new higher weights. It is significant that Guy, E.R.F. and Atkinson, who use Gardner engines on many of their models, should go for Cummins vees in their new designs. And this in spite of the uncertainty on how operators will receive the American units, particularly with no plans yet announced by Cummins for a comprehensive servicing scheme. One wonders if there would have been this swing to Cummins if the strongly rumoured increase in maximum speed and power of the Gardner 6LX had been brought into effect. For it is equally worthy of note that E.R.F. and Atkinson are showing LX-powered chassis and that, although the Cummins V6 is standard, Guy is featuring a 13ig J with the 6LX.

With the variety of Cummins engines to be seen at Earls Court, it will be worthwhile to set down details of the various types existing, The NH in-line six-cylinder series have been used from time to time in British vehicles and are, in fact, made by Cummins at its factory in Shotts, Lanarkshire. There is a variety of bore and stroke dimensions with these units and the power output is denoted in the designation, for example, the NH 220 has a gross out

Gt? put of 220 b.h.p. The maximum speed of the NH engine is usually around 2,000 r.p.m., that of the Cummins vee engines being much higher.

There are two basic Cummins V-engine designs; the V6 VAL and the V8 VALE are the relatively new lightweight engines which were announced in The Commercial Motor of February 21, 1964. Production of these units is due to commence next year in the Darlington factory run by the joint company formed by the Cummins and Chrysler companies. The Vb VIM and V8 VINE are heavier units and are currently built in the U.S. and in Germany by Krupps, but will eventually be produced in England by the company to be formed by Cummins and Jaguar, which was announced only a few weeks ago.

Bore and stroke dimensions of the VAL and VALE engines are the same at 4-625 in. and 3-5 in. respectively; giving a capacity for the VAL of 352 Cu. in. (5-75 litre) and for the VALE 470 cu. in. (7.7 litre). Maximum net output of the V6.140 VAL, which in the engine currently offered is 136 b.h.p. at 3,000 r.p.m. with maximum net torque 226 lb. ft. at 1,700 r.p.m. The only version of the VALE so far announced is the V8.185 which gives a maximum net output of 178 b.h.p. and torque of 298 lb. ft. at the same speeds as the V6.140. Probably because these lightweight engines are so new, the outputs of the sole versions are lower than will eventually be the case and it is known that plans are in hand to increase the maximum speed to 3,600 r.p.m. which will give 150 b.h.p. to the VAL and 200 b.h.p. to the VALE.

But in the case of the VIM and VINE a number of forms are offered. all of the same basic engine. The bore and stroke dimensions are common at 5,5 in. and 4.125 in. respectively which gives capacities of 588 cu. in. (9.6 litre) for the V6 VIM and 785 cu. in. (12.86 litres) for the V8 VINE. The most commonly used versions are the V6.200 with a maximum net output of 192 b,h.p. at 2,600 r.p.m. and maximum net torque of 435 lb. ft. at 1,800 r.p.m., and• the V8.265 which produces a maximum net power of 254 b.h.p. and maximum net torque of 575 lb, ft. at the same speeds in each case.

Continued on page 105

Other forms of the VIM and VINE as used in vehicles at the Show have different outputs, which are obtained by alteration to the fuel system, variation of the maximum speed, or both methods. The V6.170 used by Guy in some of the Big I goods models has a reduced fuel delivery and produces 170 b.h.p. net at 2,600 r.p.m. and 375 lb. ft. net torque at 1,700 r.p.m., whilst the V6 used for the bus version of the Daimler Roadliner has its maximum speed reduced as well as the fuel delivery and gives 150 b.h.p. net at 2.100 r.p.m. and 405 lb. ft. torque at 1,200 r.p.m.

Increasing the maximum speed of the V8 to 3.000 r.p.m. in the Thornycroft Nubian Major results in an increase in maximum power to 288 b.h.p. net at this speed, although the maximum torque is the same as the V8.265-575 lb. ft., but at 2,100 r.p.m. The reverse is the case with the V8E235 used by Atkinson. which is an economy version of the V8.265 with the main change being a reduction in maximum speed to 2.300 r.p.m. At this speed maximum output is 220 b.h.p. net. The maximum net torque is 568 lb. ft. at 1,600 r.p.m.

It is likely that the situation will get more complicated when increased power ratings for the VAL and VALE are introduced. And turbocharged versions of all the Cummins vees will eventually be obtainable.

When considering the effect that the use of the higherpower engines will have on performance of vehicles running at the higher weights now permitted, it is worthwhile con sidering the positions before and after by taking a few examples. These are shown on the accompanying table, where it will be seen that only in live cases has the new vehicle at the Show a higher power-to-weight ratio than the earlier equivalent model, running, of course, at the previous maximum gross weight.

The comparison is not really fair in all cases, for, as pointed out earlier, the Leylands had engines more powerful than usual before the Regulations came out; and in the case of the Dennis Maxim 32-ton gross six-wheel tractive unit, it is anticipated that by the time the vehicle goes into production a higher-rated version of the V8.185 VALE will be available.

This list of power-to-weight ratios shows a surprising variation in the figures for the new models. Even amongst the vehicles from one manufacturer, there is a wide difference in some eases. This is nothing new, and it seems to me that if a particular ratio is desirable, as indicated by its selection for one vehicle in a range, then surely other vehicles produced should be designed with a similar figure. Amongst the worst examples of this are tractive unit models based on shortened rigids and without any change of engine, increasing the weight rating sometimes by over 100 per cent.

It is interesting that the LPS 1620 shown by Mercedes Benz is designed for a gross train weight of 30 tons and with a 200 b.h.p. engine gives a power-to-weight ratio of 6-67. So it would appear that British vehicles are well up to the Continental requirements as far as engine power goes at the moment. But it is likely that 10 b.h.p. per ton will be a requirement across the Channel at some time in the future, and some British operators are of this opinion too. Many that I have spoken to have said that the engines fitted in the 30-ton machines at the Show have an inadequate power.

With the changing pattern of British roads, it is likely that engines of up to 280 or 300 b.h.p. will have to be used in British vehicles. But what type of engine will these have to be? It looks as though in-line engines have reached about the maximum physical size that it is practical to have in a forward-control vehicle. If you look at the Leyland and A.E.C. tilt cab, you will see that the engine cover takes tip a considerable amount of room in the cab. On the other hand, the cab on the Guy Big I chassis with Cummins engines has quite a low engine cover and as a result, incidentally, gives a more spacious appearance. The same applies to the Dennis Maxim', which is also Cummins-powered and the Seddon Supa-Cab on the 13 : Four with a Perkins engine.

The future for maximum gross machines would seem to be, therefore, V engines or turbocharged in-line units, or possibly applications of the Perkins Differential Diesel Engine principle to existing units. The Perkins D.D.E. in its present state of development can be seen on the company's Stand at Earls Court and consists of a fairly standard Perkins 6.354 with a screw-type supercharger driven through a differential gear train, which increases the output of the charger according to the need for greater engine torque.

A normal gearbox is not required as the D.D.E. can be used with a torque converter alone, although to obtain adequate gradient performance with high maximum speed a two-speed gearbox is used. The design provides high torque at low revs-the maximum figure indicated is around 400 lb. ft. at 1,400 r.p.m.-and the engine's power output is increased to 186 b.h.p, at 2,800 r.p.m, compared with 114 b.h.p. at the same speed for the standard 6.354. When announced in April this year, it was reported that the D.D.E. principle could be applied to any conventional engine and when used in conjunction with, say, a 200 b.h.p, unit could lift its output to nearly 300 b.h.p. without, weight or size penalties.

There is also, of course, the possi bility that British manufacturers will produce engines having a vec layout and, if there was a desperate need, no doubt we should see some trend towards turbocharging. There is still no sign of turbocharged diesels finding any real favour with British operators or manufacturers, only Foden showing an engine fitted with one of these units. In view of the acceptance of this easy way of increasing the power of an existing unit in the U.S. and on the Continent (using, incidentally, the British Holset turbocharger in many cases) the reason is hard to find. It is likely that the resistance to turbocharging is because of early bad experiences in the way of failures and it is not realized that well-designed units are now available.

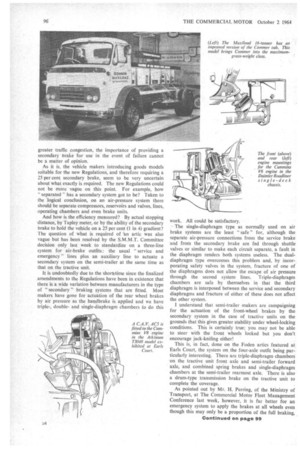

Looking now at cabs: there have been slight moves in the past to make things better for the heavy vehicle driver, but not until the 1962 Show was there anything for heavy vehicles comparable to the Commer and Bedford TK cabs. In 1962 the Show saw new Foden, Scammell and the E.R.F. units which made the news; this year it is the Ergomatic tilt cab which is fitted on Leyland, A.E.C. and Albion chassis, the variants of the Motor Panels cab used by Guy and by Seddon, the Austin and Morris Fi tilt cab and the Atkinson Guardsman cab. The Commer cab was already to a high standard and is improved to a Luxury-Plus version for the Maxiload, as also is the unit used on the Dennis Maxim, which has the external appearance of the Pax V cab but has better instrumentation, interior trim, seating and insulation. Criticism has frequently been levelled at British manufacturers for the low standard of cab offered, but with all these new designs and the Foden, E.R.F., Scammell and Bedford TK units already in existence, the British product can stand up to, and beat in most cases, overseas competition. This can be confirmed by comparing them with the cab on the Mercedes-Benz LPS 1620 tractive unit at the Show.

All the new cabs have a single-step entry forward of the front wheels which is a most commendable feature from the point of easier access, and it is therefore surprising to see the reversion to an over-the-wheel entry on the E.R.F. 2LV cab and the version of the Michelotti-designed Routeman cab fitted on the Scammell Highwayman III. I know that some operators are against the forward-entry design because of the increased damage in the event of accidental bumps at the front comers.

With the new C. and U. Regulations linking the maximum permissible weight to the front-to-rear axle spread, it is also possible that the cabs have been put back over the front-axle in order to reduce the front overhang to get the maximum spread possible within the allowable overall length. But there should be no problem in this respect on fourand six-wheel rigids, nor for that matter with eightwheelers where overhang is not critical.

In the case of four-axle artics, there is no problem in getting the axle spread to allow 30 tons even with a forward-entry cab. Possibly manufacturers are thinking about getting the minimum overhang so as to make it possible to get 32 tons on a four-axle artic but, with the axle spread of 38 ft. required for this gross weight, only long-length semi-trailers operating under Special Types Regulations can come into this category. To get a 38-ft. spread within an overall length of 42 ft, 7 in. means a combined front and rear overhang of 4 ft. 7 in.—which is hardly feasible!

To some extent it is invidious to single out any of the new cab designs for special mention as all are of a very high standard and are considerable improvements on their predecessors. But if there was a cab competition at Earls Court and I was one of the judges, I would give my vote to the Leyland Ergomatic. One of the most interesting things about the fitting of this cab by the three members of the Leyland Motors Corporation is that on the models offered with it there is no optional, cheaper cab. One of the answers to criticisms of poor cabs in the past has been that operators would not pay the high prices involved. This may be true and as long as there was only a limited market for a well-designed cab the price would never come down because it could not be made in economical quantities. By having the Ergomatic cab fitted on Leyland, A.E.C. and Albion vehicles and therefore increasing the market for it, L.M.C. has overcome this problem.

It would be very difficult to have a custom-built cab fitted on any of the chassis designed for the Ergomatic, Ln fact virtually impossible except at a very high price, so that if an operator wants one of the new vehicles (and these are the only A.E.C., Leyland and Albion models designed for the increased weights and dimensions) he will have to have the new cab. Because there is this forced market there can be a sufficient production to make the price attractive; Sankey, who are building the cab, have laid down a production plant capable of building 500 per week. In the end nobody really loses, least of all the driver, and from reports I have heard models in the Leyland Freightline range with the Ergomatic cab and increased weight ratings cost only £200 to 000 more than the earlier comparable models.

Similarly, the Motor Panels cab used by Guy and Seddon, so far as the basic structure goes, can also be produced at a lower price than if only one firm were using it. Both the Guy and the Seddon versions are well trimmed internally, have well laid out controls and offer a good degree of driver comfort. When the Cummins V engines are fitted, the unit can be tilted forward. This is, however, only intended to be done for major engine work and a fair amount of dismantling has to be done to carry out the procedure.

Having no less a degree of luxury is the new cab fitted by Dennis on the Maxim. This is of all-reinforced plastics construction (including structural members) and the internal fittings and trim are better even than on the Pax V model, which itself is to a good standard. The seats look particularly attractive and are very comfortable, the controls are well placed and there is plenty of room for storage of papers and the like.

The Atkinson Guardsman cab is particularly interesting because, by clever design, it has been possible to provide forward-entry whilst retaining virtually the same bumperto-back-of-cab dimension as on the existing Atkinson unit, which is, of course, an over-the-wheel entry cab. The doors are not as wide as on many other forward-entry cabs, and perhaps this is a good thing as the load on the hinges s reduced; the sides of the cab behind the doors are used o provide drop windows which can be used by the driver on his side) for reversing.

Austin and Morris are the only high-quantity producers of commercial vehicles with a new range of medium-weight vehicles at the Show, these being the FJ design; and one Pf the most important features is the tilt cab. The tilt mechanism incorporates torsion-bar assistance and only a slight amount of work has to be done in the way of dismantling parts to get the cab ready for tilting. Interior trim and driver facilities and comfort have been given a considerable amount of attention; because the engine is mounted below the floor (actually under the seats) a completely clear floor is provided with space and seats for two passengers as well as the driver. Full instrumentation is a strong point of the design and access to the engine without the cab tilted is comparatively good.

Looking at the new goods models to be seen at the Show there is something about every one of them which is worthy of note and commendable. Many of them are, however, untried designs and it will be interesting to see how they work in practice.

From the design point of view, probably the most advanced technically compared with the concern's previous models is the Dennis Maxim range, which has the Cummins lightweight V8-185 VALE driving through the well-designed Dennis gearbox developed for the Pax V. The fourwheelers have a rear axle made by Centrax Ltd. under licence to Rockwell Standard of America and the sixwheelers a double-drive Moss bogie. Construction of the chassis appears very robust and two important features are the virtual elimination of the need for greasing and the full specification, which includes items normally listed as extras.

En the medium-weight category the two new ranges are the B.M.C. FJ and the Seddon 13: Four. Both have many good points as well as the improved cabs already referred to; the FJ has an advanced braking system and a generally high standard specification, whilst the 13: Four also has many good features which, although not departing from convention, add up to a very workmanlike design with a good deal of attention paid to maintenance and braking.

The Guy Big J must be included in any list of the most important new models at the Show. The Cummins V6-200 or V6-170 are fitted as standard on the Big J and it is interesting to consider here that when these units are produced by the company to be formed by Jaguar and Cummins, Sir William Lyons will head a group which is comparable to that of the Leyland Corporation in that it will be producing cars, goods and passenger vehicles and will, in effect, be producing its own engines. A good deal of thought has obviously gone into the design of the Big J and an interesting aspect is the way in which the functions of certain chassis components have been made to do more than one job. For example, the .battery carrier brackets provide support also for the spare wheel carrier and the cab and engine rear support brackets also serve as the mounting for the front dampers and carry the air-intake trunking.

Leyland Motor Corporation members have a wide range of new models at the Show: from the Leyland 2-tonner in its new uprated form as the " 90 " to the more powerful Major version of Thornycroft's Nubian. Between these lie the A.E.C., Albion and Leyland chassis with the new tilt cab and new chassis components in varying degrees, while Scamrnell's Handyman III is a new model and the Townsman three-wheeled tractive unit is new in appearance-and altered in specification.

No one will deny that a good deal more consultation

should take place between tractiVe unit makers and semitrailer makers in the production of matched outfits. This is increasingly important with the higher gross weights now permitted, and the greater stress laid on braking. Fodens departed from the usual practice at the last Show with a matched outfit produced in conjunction with R. A. Dyson and Co. Ltd. and at this Show the two new models exhibited by the concern come in a similar category. The most novel, the eight-wheeler load-carrying tractive unit and single-axle semi-trailer, 'could have many useful applications. . The matched four-axle artic is principally of interest for its braking system, which has already been referred to. Another point is that the semi-trailer has running gear consisting of Foden components and brings Fodens into the same position as Scammell in that operators can go to one supplier for spares for both parts of the artic outfit.

Another important new model is the Commer Maxiload, which marks the entry of the concern into the maximum-load-capacity class, as the model is available for a 14 or 16 ton g.t.w.

Completing the list of exhibitors of new goods chassis are Atkinson and E.R.F., and on these stands Cummins engines figure prominently. The Atkinson tractive unit shown with the Guardsman cab has a V8E-235 and is designed for 30 tons e.t.w., whilst Cummins in-line as well as vee units are a feature of the new E.R.F.s. As all the new chassis are designed for the higher weights, improved braking systems with air-powered secondary brakes are employed (as they are also on the new Commers).

Turning now to passenger vehicles we find that interest is restricted to rear-engined p.s.v. for, apart from the new models, there have been changes also in the Leyland Atlantean and Daimler Fleetline.

The newest single-decker is really the Daimler Roadliner, for the Leyland Panther Cub is a development of the Panther which was introduced at the Amsterdam Show this year and the A.E.C. Swift can he said to be a separatechassis version of the integral Verheul single-decker which was developed in conjunction with A.E.C, and also shown at Amsterdam this year. Rear-engined singledeckers are nothing new (remember the Foden design of a number of years ago?) and it is surprising that it has taken so long for the engine to get to the back of the vehicle in view of the undoubted advantages in axle load distribution. In fairness, the length of time that it has been practicable to have an underfloor-mounted rear engine has only been three years, for this layout is only really possible with the longer p.s.v. allowable since 1961.

One problem of having a rear engine mounted under the floor is what to do about the seats behind the rear axle and the steps that are necessary in the gangway if a low level flat floor is needed in front of this point. Daimler illustrate a good way of getting over this on the bus chassis by having a gently i amped gangway and seat-mounting area from a low-height front entrance to the rear of the saloon. By using the Cummins V6 engine in the Roadliner, Daimler has managed to make the power unit as unobtru sive as it is ever likely to be on a p.s,v. by having it located underneath the back seat. Accessibility to the engine for maintenance is reasonably good, with wide doors at the rear, and there is good storage space at the sides.

On the A.E.C. Swift the engine cooling is a neat and compact layout, with the radiator mounted close to the rear of the vehicle on one of the side 'members and therefore needing only half the coolant of the Leyland and Daimler designs which have front radiators. The alternative on the Daimler featured on one of the Show exhibits is the new Clayton Dewandre Compass cooling system which, as well as providing for engine water temperature control, also gives heating or ventilation to the interior of the body. This has a considerable future.

Although fairly small changes have been made to the Daimler and Leyland rear-engined double-deckers, these are important ones. The reduction in weight of about 3 cwt., in the engine support members on the Fleetline will be welcome, and there has also been an improvement on engine accessibility by modification to the rear cover. On the Atlantean, the new dropped-centre rear axle permits a continuous, level floorline in the lower saloon and allows a lower overall height for the double-deck body.

Transmission Trends ,

Turning now to engines and components, one sees that, with the more urgent trend towards better vehicle performance there is a general trend in all heavy vehicles towards. six-speed boxes with overdrive top. This type of unit is• almost universal on the maximum-capacity models featured at the Show and at the top of the scale, E.R.F. use the Fuller Roadranger 15-speed twin-countershaft box in one of their new models and Fodens have re-introduced the 12-speed gearbox which, although offered until a short time ago, was rarely fitted.

Leyland have also brought out a new option on the transmission side, with a close-ratio version of the company's six-speed unit (or seven with an optional extra ratio) and this is designed for use on vehicles running on motorways for much of their life. On many of the new chassis, including Guy, Leyland and Albion, extra gearing can be incorporated in the standard gearbox to give 10 or 11 effective forward ratios. Two-speed rear axles double the potential of the gearbox also when they are fitted and the Eaton units are more frequently appearing in the specifications of vehicles these days.

Constant-mesh gearboxes continue to be the most popular type and there seems to be little interest in synchromesh by the heavy-vehicle makers. In the medium-weight category B.M.C. have gone to the new. E.N.V. five-speed synchromesh unit for the FJ range. And the multi-cone synchromesh system recently developed by Smiths Motor Accessories and featured on that concern's stand in the " gallery " may change the heavy-vehicle makers' attitude in the future, as it gives greater synchronizing torque yet demands lower gear-lever loadings.

On the passenger side, one would have thought that semior fully automatic transmission would be more or less universally specified by operators for new vehicles, particularly for bus operation where congested roads make the driver's work very hard. But manual change is still the more popular. What the story will be with rear-engined p.s.v. is really an open question, for both layouts are offered. I would consider at least semi-automatic transmission as used on the Daimler Roadliner and Leyland Panther and Leyland Panther Cub to be essential. I am surprised that A.E.C. gives the option of manual change on the new Swift and uses it on the chassis exhibited— involving about 30 ft. of gearchange linkage.

In any review of this sort, developments in components as appearing in the " gallery " at Earls Court deserve mention and if one takes a trip upstairs components used in the new chassis can be examined individually. It follows that the trends apparent in the chassis are repeated on component stands; for example, new cabs are featured by Motor Panels and Sankey, heaters by Smiths, and so on. Whilst on the Subject of cabs again, an air conditioner e36 for goods cabs is shown by E.N.V.; Smiths, Ekco and Pye have developed radios specially for commercials. Smiths' are shown on their stand, whilst the other two are fitted to new models at Earls Court.

On braking, both Westinghouse and Clayton Dewandre are featuring new components, including multi-diaphragm chambers, dual valves and the like. New Girling and Lockheed brake units and equipment giving many improvements, not only in performance but in life, can also be seen. It remains to be seen how the new units stand up in service—they have had extensive development testting—but it is reassuring to know that all manufacturers are continually striving to improve their products. Worthy of mention in connection with braking is the Hope Antijack-knife device shown by Westinghouse—a promising unit in making artics safer—and the Torquelim anti-wheelhop equipment featured by Henry Boys and Son Ltd. which is claimed to give excellent results when applied to the front axle as well as to the rear axle or bogie.

There have not been so many developments by proprietary rear axle makers for this Show as there were ir 1962, the exception being the new double-drive, double.

reduction bogie shown by Kirkstall and used in a numbei of new chassis. Universal Power Drives now offers the Eaton-Hendrickson two-leaf spring suspension for it Unipower third-axle conversions and is making a feature of this. Another American design making an appearance at Earls Court is the Rockwell Standard being producec by Centrax Ltd. of Newton Abbot, Devon, and used ir the Dennis Maxim four-wheelers.

Suspensions are generally getting better, with many good! models having longer and often dual-rate leaf springs tc give an improved ride when partly laden. Air suspensior continues to be popular for passenger vehicles and semi. trailers but there appears little or no interest for rigic goods chassis, even though there are undoubted advan tages for some kinds of load.

Semi-trailer makers are alone in making use of disc brakes but this state of affairs may change soon with tilt introduction by Dunlop of the Mark IX design. Thest can be seen on Taskers and Crane Fruehauf semi-trailei exhibits and incorporate mechanical actuation through fact earns and rollers. The design makes a new approach tc discs for heavy vehicles, as instead of being mounted te the hubs at their centres they are bolted to the edges o. drum-like components having cut-outs for cooling an inspection purposes. The Mark IX can replace drums.

Finally, steering. Here, as was to be expected, the increase in front-axle loading to six tons on four and si) wheelers built to the increased weight ratings has led tc the standardization of power-assisted steering in most cases Burman steering continues to be popular, but so doe: Marks, the latest design of which has a triple roller.

This 1964 Show illustrates more than any others in recen times that the British vehicle designers are as capable a: their counterparts in other countries. It is always easie to produce models for home consumption than it is fo markets where regulations and operating practice are ver different and the changes in the U.K. regulations will )3( a good way to helping the design of chassis for export.

There are so many innovations at Earls Court that thi immediate future appears inevitably to be the consolida tion of the changes. Maybe the braking requirements wil be clarified and result in some standardization of systems Most certainly by the 1966 Commercial Motor Show ther

will be plating for all classes of goods vehicle: and possibl: type approval also. So in spite of the present flood o change, the industry will not be able to rest on the progres made and the 1966 Show promises to be of considerabl, importance.