THIRTY-NINE STEPS from 5 cwt. to 25 tons

Page 83

Page 84

Page 85

Page 86

Page 87

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

dts of 17 Months' Road Tests Analysed : .e Powerful Engines and Better Braking in Big Vehicles By The Technical Editor

PARTICULARLY wide variety of commonly used types I commercial vehicle has been road-tested by The 7ommercial Motor since the last road-test analysis was ed on May 2, 1958. They range from British and Italian heeled 5-ewt. vans to high-powered heavy-duty goods of up to 25 tons capacity, including a Swedish example turbocharged oil engine.

use the printing dispute has delayed the publication of ialysis, a larger number of vehicles than usual is red in the accompanying charts and tables, The total ested over a period of 17 months. All but four of the are British, and six passenger models are included.

of the more unusual vehicles dealt with in this ry include the Lambretta 5-cwt. van, the Guy-Carrirnore mg 4,000-gal. tanker, the Atkinson dumper, the Bedford;weeper, and the Leyland Atlantcan double-decker-the ritish rear-engined passenger vehicle to come into y production.

rig the high-performance vehicles may be cited the Fleet Special 2-ton newspaper-delivery van, the Seddon articulated outfit and the Swedish Seania-Vabis bus.

Noteworthy Advances ibly the most noticeable improvement during the period :onsideration has been with regard to the heavier goods s. in this field, noteworthy advances have been made s the production of greater power and better controlland braking. British operators have for long fought shy g bigger engines than they have considered to be really ry, but the advantages of a big engine in a heavy vehicle arted to be realized, with the result that The Commercial has been able to test such interesting vehicles as the . 21-ton articulated outfit, powered by a Cummins i.p. engine, and an eight-wheeler of the same make with cessful new Gardner engine-the 150 b.h.p. 6LX.

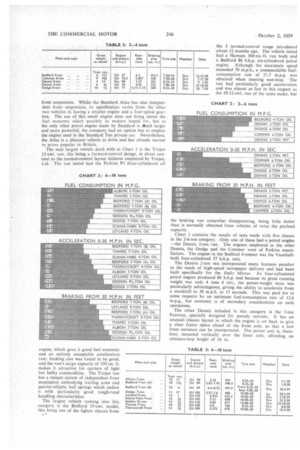

tweight goods vehicles form the subject of the first ad chart, seven vehicles falling into this category having :sled since May, 1958. The lightest two are the Italian Mta and the British Reliant 5-cwt. three-wheelers.

rison of the results obtained with these two vehicles that although the Italian design scores slightly over the Reliant in fuel economy, mainly because of its low the use of a scooter-size engine and brakes puts the :tta well down the list in respect of acceleration and performance.

fair to assume, therefore, that, interestMg though the

Italian vehicle may be, the British approach to the construction of a vehicle of this capacity offers the greatest overall advantages, not the least of these being an appreciable degree of comfort for driver and passenger and a useful maximum speed of at least 55 m.p.h.

Higher up the scale are three 10-12-cwt. vans-latest version of the Bedford CA, the new Standard Atlas, and a Thames powered by the Perkins Four 99 "baby" oil engine. The performance of these three vehicles, as indicated in Chart 1, shows the undoubted fuel-saving advantages to be derived from the use of a small oil engine in a vehicle of this type. This benefit, in the case of the Thames conversion, is not offset by sluggishness. Its acceleration rate to 30 m.p.h. was only a quarter of a second slower than that of the Bedford van which was running" 4 cwt. lighter.

Both these vans have three-speed gearboxes and independent El

Dry 1.5.59 Dry 24.4.59 Dry 30.558 'Net 6.3.59 Dry 5,12,58

Dry 3.4.59

front suspension. Whilst the Standard Atlas has also independent front suspension, its specification varies from the other two vehicles in having a smaller engine and a four-speed gearbox. The use of this small engine does not bring about the fuel economy which possibly its makers hoped for, but as the only other petrol engine made by Standard is Much larger and more powerful, the company had no option but to employ the engine used in the Standard Ten private car. Nevertheless. the Atlas is a pleasant vehicle to drive and has already started to prove popular in Britain.

The next largest vehicle dealt with in Chart I is the Trojan 25-cwt. van, this being a forward-control design, in direct contrast to the normal-control layout hitherto employed by Trojan, Ltd. The van tested had the Perkins P3 three-cylindered oil engine, which gave it good fuel economy and an entirely acceptable acceleration rate; braking also was found to he good. and the van's cargo capacity of 350 Cu. ft. makes it attractive for carriers of light but bulky commodities. The Trojan van has a unique system of independent front suspension embodying trailing arms and quarter-elliptic leaf springs which endow it with particularly good rough-road handling characteristics.

The largest vehicle coming into this category is the Bedford 35-cwt. model, this being one of the lighter chassis from

the J normal-control range introduced about 12 months ago. The vehicle tested had a Hawson 300-cu.-ft. van body and a Bedford 86 b.h.p. six-cylindered petrol engine. Although the maximum speed exceeded 70 m.p.h., a commendable fuelconsumption rate of 21.7 m.p.g. was obtained when running non-stop. The van had particularly good acceleration and was almost as fast in this respect as the 10-12-cwt. van of the same make, but

the braking was somewhat disappointing, being little better than is normally obtained from vehicles of twice the payload capacity.

Chart 2 contains the results of tests made with five chassis in the 2-6-ton category. Only one of these had a petrol engine -the Dennis 2-ton van, The engines employed in the other Dennis, the Dodge and the Commer were of Perkins manufacture. The engine in the Bedford 4-tonner was the Vauxhallbuilt four-cylindered 57 b.h.p. unit.

The Dennis 2-ton van incorporated many features peculiar to the needs of high-speed newspaper delivery and had been built specifically for the Daily Mirror. Its four-cylinderecl petrol engine produced 80 b.h.p. and because its gross running weight was only 4 tons 4 cwt., the power-weight ratio was particularly advantageous, giving the ability to accelerate from a standstill to 30 m.p.h. in 15 seconds. This was paid for in some respects by an optimum fuel-consumption rate of 12.6 m.p.g., but economy is of secondary consideration on such Operations.

The other Dennis included in this category is the 3-ton Paravan, specially designed for parcels carriers. It has an unusual chassis layout in which the engine is set back to give a clear frame space ahead of the front axle, so that a low front entrance can be incorporated. The power unit is, therefore, mounted vertically over the front axle, affording an entrance-step height of 16 in. s layout makes it particularly easy driver working by himself to gain to the payload compartment and Le street. A somewhat unusual e of the Dennis-built body is the if an upward-sliding door set at ximately 450 across the near-side corner of the body. This idea was uggested in The Commercial Motor article on the design of an ideal Is vehicle published on June 20, marked a breakaway from normal practice in vehicles is size in using 16-in.-diameter wheels. These small is offer several advantages, including a loading height ly 3 ft. 2} in. and a turning circle more akin to that of a .rd-control design. Being, a normal-control vehicle, howthe Bedford 4-tanner has a comfortable three-man cab .and engine accessibility. Its performance also proved to be and on normal delivery runs with a constantly decreasing an average fuel-consumption rate of about 18 m.p.g. should

the two 6-tanners dealt with, the Dodge was a reasonably ntional forward-control design. The Commer also had rd control, but a new Perkins six-cylindered semi-horizontal gine was mounted beneath the cab seats. Both engines had ■ ximately the same power output, but the Dodge showed ly greater economy than the Commer because of the use of an Eaton two-speed axle on the test vehicle. The slightly higher torque output of the engine in the Commer and the -t-ton lower test weight resulted in the Commer being slightly quicker off the mark than the Dodge. In braking performance, there was only /25 ft. between the two examples.

The Commer engine layout offered the advantage of unobstructed seating space in the cab, giving comfort for three people, and because of the provision of easily removable seat cushions, engine accessibility was above average for a vehicle of this size.

Five new 7-tanners are dealt with in. Chart 3. There are two Becifords both powered by the Bedford 89-bhp. six-cylindered oil engine. The 7-tonner Mark A was a. forward-control 13-ft.wheelbase model, whilst the B chassis was" a normal-control J-type 6-cu.-yd. tipper. The tipper had slightly lower two-Speed axle ratios than the forward-control vehicle, which accounted for , the slight advance in the fuel-consumption and acceleration results obtained. A more appreciable difference between the two models is to be seen in the braking figures, the proportionally higher rear-axle loading of the normal-control design and slight improvement in the braking system making a difference of over 8 ft.. in the stopping distances obtained with the two versions.

Outstanding results were obtained with the Thames Trader 7-tanner, which was powered by the Ford 6D 100-b.h.p. oil engine. The test figures show that it has a slight advantage over other mass-produced chassis of the same capacity in fuel consumption and acceleration, but the braking system leaves room for improvement.

A fine example of a high-quality 7-ton chassis is to be found in the latest Albion Chieftain model. which was road-tested in its native Sea land. This chassis has a 90-b.h.p. fourcylindered oil engine and double-reduction rear axle, and a particularly good fuelconsumption result was obtained on test. The cab is set well forward, so that the entrance step can be placed low ahead of the front wheels. The Chieftain was the heaviest of the 7-tonners tested, although it falls into line with the usual Albion policy of producing a robust chassis to give many years of trouble-free service. As with the Trader, however, the braking system could well be revised.

The remaining 7-tonner dealt with in Chart 3 is the Dodge forward-control tipper, part of the test on which was conducted on a constructional site of the London-Yorkshire motorway. The test was made in adverse weather, the roads being icecovered for most of the time, and this explains why no braking figures are quoted. The braking system is powerful, however, and good figures would have resulted had it been safe to make full-pressure tests.

Of the three 9-tonners tested, the Thornycroft Mastiff takes pride of place. It is a 14-ton-gross design following in the footsteps of the high-performance Trusty eight-wheeler made by the same concern. As can be seen from the chart, the Mastiff offers low fuel costs. lively acceleration and a high standard of braking, whilst a heavy-vehicle driver could ask for little more in the way of cab comfort, driving fatigue in particular being reduced by the quietness of the power unit.

Another modern British 9-tonner is the Leyland Super Comet. the test report of which appears in this issue. Reference to the road-test data pand on page 260 shows that a comprehensive set of fuel-consumption figures was taken, including laden and unladen circuits of the Preston by-pass, which remains Britains only motorway until the opening of the LondonBirmingham road next month. The Super Comet has been built with high operating speeds in mind and it is particularly pleasant to drive, the high standard of braking being most reassuring at speeds in excess of 60 m.p.h.

The third 9-tonner dealt with in this chart is the Swedish Scania-Vabis, a normal-control design with a 165-bhp. oil engine, intended for the most part for use with a drawbar trailer. The Scania-Vahis was tested solo at a weight of over 15 tons, and gave good fuel economy, exceptional acceleration but rather disappointing braking. As is usual with Swedish vehicles, cab comfort was first-rate and the high power-weight ratio when operating solo produced an exceptional gradient performance.

Too Powerful Brakes

The remaining vehicle in this category is the Seddon 91-tonner, a relatively lightweight chassis powered by the same engine as is used in the Leyland Super Comet. The Seddon showed good fuel economy, although it was not fitted with the optional overdrive top gearbox w.hich may be used with this Leyland engine, and its acceleration performance was acceptable by British standards for a maximum-weight four-wheeler. It was remarked in the test report that the braking system was. if anything, a little too powerful, all the wheels having locked when making emergency stops from 30 m.p.h.

Chart 4 shows the performance of eight widely differing vehicles. This category ranges from a 12f-ton-payload sixwheeler conversion to a 25-ton articulated outfit. The vehicles include one of the first British air-sprung designs—a 4,000-gal. spirit tanker—and the first turbocharged chassis to have been subjected to a full-scale road test.

The 121-ton six-wheeler was a Leyland Comet I2-ton-gross chassis which had been converted to take an Eaton-Hendrickson rubber-suspended walking-beam trailing-axle bogie, and the test was carried out at a gross weight of just over 171 tons. Good braking and fuel-consumption figures were obtained with this conversion, but, as might be expected in view of the lower power-weight ratio, the acceleration performance was not exactly exhilarating. The conversion was basically sound,

F.4

however, and the vehicle was 'judged to he completely satisfactory.

Another lightweight six-wheeler tested was the Rowe Hillmaster, which was carrying a 14-ton payload. It had an A.E.C. 122-b.h.p. oil engine which gave it a surprisingly livery performance without excessive fuel consumption. The braking tests were marred by wet roads and the results would have been some 10 ft. better had conditions been more suitable.

The Leyland I5-ton outfit included in this category was a Super Beaver normal-control export four-wheeler with a drawbar trailer. It was unfortunate that the vehicle offered for test had been designed for desert operation and was equipped with an extra-low-ratio axle. This gave good acceleration, but a higher fuel-consumption rate than would be expected. An auxiliary gearbox afforded an exceptional gradient performance, but, again, because of the low gearing, its maximum speed was little more than 30 m.p.h.

The Seddon 0D8 has so far been the only vehicle tested by The Commercial Motor with the Gardner 6LX 150 b.h.p. power unit. This new engine offers many advantages over the 6LX which had hitherto been used in many British eightwheelers, giving appreciably better acceleration without noticeably heavy fuel consumption. The Seddon chassis had eight-wheel braking, a feature becoming

increasingly popular on eight-wheeled chassis, and even on a wet road the vehicle was brought to rest from 30 rn.p.h in 64 ft.; this distance would have been nearer 50 ft. had the road been dry.

An equally outstanding Seddon vehicle was the 21-ton-payload "ark." which was tested with a Cummins 170-b.h.o. oil engine. The overall performance reached a high standard and illustrated the advantages to be obtained from the use of a high-powered engine in a heavy vehicle, particularly in respect of rapid hill-climbing and the ability to maintain a high average speed on busy roads.

Dunlop air suspension was fitted to the driving axle and the semi-trailer axle of the Guy-Carrimore tanker. Somewhat hair-raising tests made with this outfit demonstrated the virtual impossibility of turning it over. The advantage of air suspen

n reducing unladen weight was seen by the capacity of Lnker: hitherto it has been necessary to use eight-wheeled s for 4,000-gal. loads. An A.E.C. engine powered this and gave good economy and acceleration, whilst the .g performance was exceptional, again in no small way ) the air suspension.

heaviest vehicle tested in this category was the A.E.C.— rs low-loading 25-ton articulated outfit. The normal d tractor had an A.E.C. 162 b.h.p. engine and the tests made with a payload of 22 tons 12 cwt. Braking was whilst fuel economy was surprising in view of the someunhelpful traffic conditions under which the tests had to lantages of turbocharging were shown to the lull by the nade in Sweden with the Volvo L495 four-wheeler, which rawing a 16-ton gross trailer. This was an outstanding a in all respects, not least with regard to the ig. The distance obtained with the trailer from 30 m.p.h. nly 8 ft. greater than when running solo.

ir special types of vehicle are considered in Chart 5. The it is the Austin-based ambulance which is being produced ndon County Council for their own purposes. An Austin forward-control petrol-engincd chassis with a De Dion axle gives a low floor line and good suspension ateristics.

s is the second vehicle of its type to be tested. The engine Mangoletsi manifold and the gearbox was a Hobbs fully latie unit. The Mangoletsi manifold had been fitted to cold-start" economy, whilst the Hobbs gearbox was to provide good acceleration characteristics without g on the skill of the driver and without detriment to the onsumption rate..

Oil Engine Fitted in Sweeper

3edford oil engine powered the Bedford-Lacre sweeper, was tested in Welwyn Garden City. Two sets of fuelmption figures are shown in the chart, one while sweeping ne while not sweeping, and both indicate the advantage gained in the use of an oil engine for this type of ipal vehicle. The sweeping equipment proved to be lay efficient and the dry, dusty roads over which the were conducted emphasized the necessity of an effective .sprinkling system, such as was fitted to the Lacre design. Thames 4 x 4 included in this category was an All Wheel conversion of the Trader 7-tonner, and tests made on an

proving ground revealed an outstanding gradient .mance.

ummins engine powered the Atkinson dumper, which asted at a weight of 25 tons 17 cwt. A dumper is not icle with which fuel economy is of first importance, but e low gearing a figure of 7.7 m.p.g. was obtained. :ration was also good, whilst the powerful braking system ble to bring the vehicle to rest from 30 m.p.h. in 76.5 ft. g a thunderstorm which raged with almost tropical ity.

the six passenger vehicles dealt with in Chart 6, three coaches and three were buses. The A.E.C. Reliance s was an export model with a high maximum speed, gradient nerformance and praiseworthy fuel economy.

The Bedford 41-seat coach (which. had a Duple body) was taken on an 859-mile high-speed run through England, Wales and Scotland at an average speed of 31.8 m.p.h., and returned a consumption rate of 17.4 m.p.g.

The Guy coach chassis was a Victory model intended for export and powered by a Gardner 6HLW oil engine. The tests were made with a variety of rear-axle ratios, but the results indicated good fuel economy. Braking was exceptional for a vehicle of this weight.

The lightest of the three bus chassis was the Seddon with an A.E.C. 98 b.h.p. oil engine. This chassis, as with the A.E.C. and Guy examples, had an underfloor engine and its overall performance was entirely satisfactory. The other two buses were both high-capacity vehicles with several unusual features. The Leyland Atlantean double-decker has its engine at the rear to allow the provision of a wide entrance ahead of the front wheels and easy loading for the 78 passengers who can be seated in the body. No braking figures are quoted, because a loose test load was being carried and to make emergency stops from 30 m.p.h. would have caused extensive body damage.

The Scania-Vabis bus had only 46 seats, but space for 28 standing passengers. The engine was similar to that used in the Scania-Vabis 9-tanner. It gave particularly good fuel consumption and brought the bus to the top rank as far as acceleration is concerned. This design also had a front entrance, but the engine occupied a conventional forward position, thereby simplifying the underframing layout of the integral body.

Maintenance Tests on 19 Vehicles

(IF the 39 vehicles dealt with in the performance charts, maintenance tests were conducted on 19 of them. These tests revealed that generally there had been little advance in the standard of unit accessibility provided by manufacturers over the 17-month period under consideration.

Possibly the most outstanding vehicle in the matter of maintenance was the Leyland Atlantean, which, by virtue of its rear engine position, was able to offer engine accessibility far in advance of that normally available on a passenger vehicle. This facility was, admittedly, obtained at the expense of a clean rear outline, but the position of the engine conferred the further advantage of isolating noise from the passenger saloons.

The vogue for forward control on lighter vehicles is presenting maintenance problems; the old style of +-ton van based on a private car had engine-accessibility advantages, whatever its disadvantages might have been. Nowadays the trend is towards large load space without consideration for the accessibility of the power unit, an item which appears to be placed wherever there is room for it.

Among the larger normal-control models there are signs that engine-cowl panelling is being tailored to suit the maintenance man. This is evidenced by the Albion Chieftain and the Leyland Super Comet, which have large one-piece removable panels which enable the greater part of the power units to be reached conveniently.

An exception to the normal line of thought is seen in the Bedford 7-type 4-tanner, which, because of its small wheels, is able to offer the manceuvrability of a forward-control chassis with the same body length, but with engine accessibility usually obtainable only through a normal-control layout. The small wheels are of material benefit in this respect, in that the front-wing line is lower, thereby making the engine easier to reach.