Who dares, wins Would you walk away from your highly

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

respected, family-owned engineering business and instead use a greenhouse to hatch plans of creating a dream? That's what Edwin Richard Foden did in 1933 when he defied the odds to create ERF Words/images: boo fuck It's hard to imagine the upheaval at the time. The depression of the late 1920s was a tough time for many manufacturers as they fought to keep afloat, but it didn't help when a company was tearing itself apart through in-fighting. The business in question was the highly respected truck builder Foden, but causing the discontent was the management's belief that steam was the way to go. This mode of propulsion had kept the company going for more than 75 years and, surely, the new-fangled oil engine was just a flash in the pan.

While that may have been the Foden board's policy in 1932, it wasn't the belief of the father and son duo of Edwin and Dennis Foden. Edwin was then Foden's engineering director and, while the compression ignition (diesel) engine may have been relatively new to the market, the pair felt Foden was missing out by not embracing this new technology to change their product range. But could their vision make a difference?

Daughter's greenhouse Of course, Edwin and Dennis didn't create what would be ERF just by themselves. The pair were initially joined by retired Foden manager George Faulkner, while Ernest Sherratt brought his ex-Foden experience to the group and became the new vehicle's designer.

Edwin left Foden at the end of 1932 (saying he had retired) and the group of four founders had their first meeting together in the greenhouse at Hilary House, the home of Edwin's eldest daughter in Elworth near Sandbach. This took place just after Easter and little did the quartet realise that by 1 September 1933, the first-ever vehicle bearing the ER Foden Diesel name would have already been delivered to its first owner.

Best of British Sherratt started with just a blank sheet of paper, but his brief for building the first ERF 12-ton gross fourwheeler was straight-forward: make it simple, build it strong — albeit as light as possible — and make it reliable. This recipe was followed by ERF throughout its 75 years in production.

ERF was able to get up and running so quickly because it adopted a proprietary build for its new vehicle construction.

So rather than like the Foden manufacturer — which built everything from engine, gearbox, axles, cab — ERF had others build the components and the company simply put them together. It also convinced its suppliers that they should let it have the parts on a sale or return basis — and the trust they had in Edwin meant they all agreed.

In the early 1930s, Gardner diesel engines were just being accepted and ERF was one of the first to exploit this frugal and reliable power pack. Together with the 4LW engine, the new ER Foden would have axles made by Kirkstall, a gearbox made by David Brown, brakes made by Lockheed/Clayton Dewandre and a cab made by local coach builder JH Jennings.

It was Jennings who also provided the space for the first ER Foden factory and, in June 1933, the 10-strong production team took up residence to build the first vehicle.

One of the many good things about being an ERF fan is that so many examples of the marque have been saved for preservation. This includes the company's first ever vehicle, the MJ 2711, which was restored by company apprentices around 1971 and has been a regular on the preservation scene ever since.

The vehicle was given the number 63 to coincide with Edwin's age at the time. The vehicle was first owned by Fred Gilbert of Leighton Buzzard with the salesman — who did that first deal — being Ted Foden who was working on a freelance basis.

Marketing of the new ER Foden Diesel was based on how easy the vehicle was to drive. Naturally, that created a lot of interest, while even more interest in the new Cheshire manufacturer was generated when the firm exhibited at the Olympia Exhibition in London. However, one sour note from this exhibition wa the objection by Foden to the use of the ER Foden Diesel engine name. So the initials ERF came to the fore — and the spat only succeeded in giving ERF even more positive publicity.

One huge slice of feedback the new ERFs soon generated was that operators found them strong. So strong, in fact, that rather than load these early four-wheelers with the six tons that ERF suggested was their payload, they'd load another two tons to reach the 12-ton gross weight, which back then was the legal maximum for four wheelers. Hauliers also felt the ERF strong enough to pull a drawbar trailer. To compensate for this extra weight, the five-cylinder 5LW engine became standard fitment in what was then to be the CI5 model.

ERF built 31 trucks in its first year of trading, 96 in year two and 413 by 1938. ERF did so well because operators found the trucks ideal for what they wanted — and they told others how good they were.

The snowball started to roll and ERF began making sixand eight-wheel rigids plus four-wheel tractor units for articulated use. And some of these vehicles were even heading for export to South Africa, which was one of the company's long-term favoured markets.

Bigger vehicles meant bigger engines, with Gardner's biggest then being the 6LW — producing 102bhp. The success of ERF was also a great platform for Gardner, and eventually buyers from the likes of Scammell, Atkinson and even Foden, were joining the end of the customer line as these too were keen to get the same power plant that ERF was using. The subsequent downside to this long queue of customers was the increase in delivery time.

Ups and downs One of the drawbacks to being a new manufacturer is the difficulty in generating growth. In fairness to ERF, the problems it hit were often outside of its control. The Second World War saw priority given to the war effort, while the late 1940s was a time for rationing and extreme shortages. If that wasn't bad enough, Edwin died in 1950— pushing the company into going public on the stock exchange. But by the mid-1950s, the company launched its KV range and when Gardner eventually produced its slightly bigger 6LX-150bhp engine, hauliers were at last getting a modern-looking vehicle that was fit for purpose.

Having a proprietary build allowed ERF to use parts from a variety of sources, and by the late 1950s it began offering both Cummins and Rolls-Royce engines (both diesel and petrol variants) as an option to the Gardner.

They were early in offering disc brakes (sadly not then a success) but they led the transition to using spring brake units and took on board Fuller nine-speed range change gearboxes as an option to the old David Brown.

One thing ERF was slow in producing was the tilt cab, however, as that didn't come until the launch of the B Series in 1974.

Peter Foden To many, Peter Foden was the face of ERE His elder brother Dennis died in 1960 (then only 60) and Peter took on the role to lead ERF and stayed there until the firm was bought by Western Star in 1996.

It was a long-standing trait of ERF that once they had an operator's business, it tried hard to keep them. We like the story Jack Richards tells of how, after buying his first second-hand ERF in the mid-1960s, local dealer Sellers & Batty asked if he'd like to visit the ERF factory and have lunch with Peter and Eric Green. That visit was to have a huge positive effect on Jack, who resolved to buy ERFs as soon as circumstances allowed. And he certainly did that.

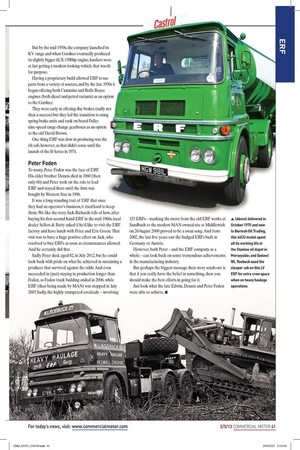

Sadly Peter died, aged 82, in July 2012, but he could look back with pride on what he achieved in sustaining a producer that survived against the odds. And even succeeded in (just) staying in production longer than Foden, as Foden truck building ended in 2006, while ERF (then being made by MAN) was stopped in July 2007. Sadly, the highly trumpeted cavalcade — involving 153 ERFs — marking the move from the old ERF works at Sandbach to the modern MAN-owned site at Middlewich on 26August 2000 proved to be a swan song. And from 2002, the last five years saw the badged ERFs built in Germany or Austria.

However, both Peter — and the ERF company as a whole — can look back on some tremendous achievements in the manufacturing industry.

But perhaps the biggest message their story sends out is that if you really have the belief in something, then you should make the best efforts in going for it.

Just look what the late Edwin, Dennis and Peter Foden were able to achieve. •