E When Australian operators say long distance they do mean

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

long—it's further from Perth to Brisbane than from London to Moscow. They also have to cope with some of the toughest roads in the world: in the far-reaches of the outback tarmac is for sissies.

Tough conditions breed some unique trucks and Commercial Motor has been to see some of the operators who run them, courtesy of Scania, one of the European truck makers competing for a slice of the Australian market.

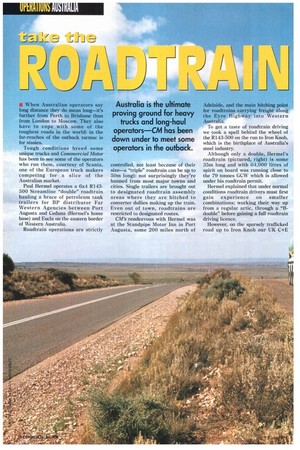

Paul Hermel operates a 6x4 R143500 Streamline "double" roadtrain hauling a brace of petroleum tank trailers for BP distributor Far Western Agencies between Port Augusta and Ceduna (Hermel's home base) and Eucla on the eastern border of Western Australia.

Roadtrain operations are strictly controlled, not least because of their size—a "triple" roadtrain can be up to 50m long): not surprisingly they're banned from most major towns and cities. Single trailers are brought out to designated roadtrain assembly areas where they are hitched to converter dollies making up the train. Even out of town, roadtrains are restricted to designated routes.

CM'S rendezvous with Hermel was at the Standpipe Motor Inn in Port Augusta, some 200 miles north of Adelaide, and the main hitching point for roadtrains carrying freight along the Eyre Highway into Western Australia.

To get a taste of roadtrain driving we took a spell behind the wheel of the R143-500 on the run to Iron Knob, which is the birthplace of Australia's steel industry.

Although only a double, Hermel's roadtrain (pictured, right) is some 35m long and with 64,000 litres of spirit on board was running close to the 79 tonnes GCW which is allowed under his roadtrain permit.

Hermel explained that under normal conditions roadtrain drivers must first gain experience on smaller combinations; working their way up from a regular artic, through a "Bdouble" before gaining a full roadtrain driving licence.

However, on the sparsely trafficked road up to Iron Knob our UK Ci-E cence passed muster. Moving out of own the outfit tracked surprisingly ell round tight junctions, helped by he double pivot point of the second ifth wheel and A-frame coupling on e converter dolly.Out on the gently dulating two-lane Eyre Highway the 00hp vee-eight Scania made light ork of the job.

44'L"4111/114104

Well run in

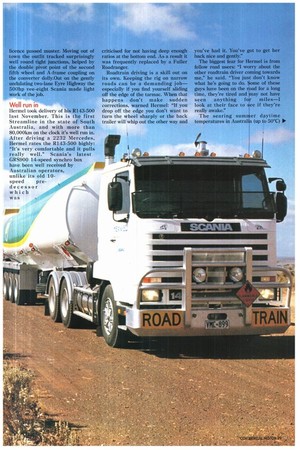

Hermel took delivery of his R143-500 last November. This is the first Streamline in the state of South Australia, and with more than 80,000km on the clock it's well run in. After driving a 2232 Mercedes, Hermel rates the R143-500 highly: "It's very comfortable and it pulls really well." Scania's latest GRS900 14-speed synchro box have been well received by Australian operators, unlike its old 10 speed predecessor which was criticised for not having deep enough ratios at the bottom end. As a result it was frequently replaced by a Fuller Roadranger.

Roadtrain driving is a skill out on its own. Keeping the rig on narrow roads can be a demanding job— especially if you find yourself sliding off the edge of the tarmac. When that happens don't make sudden corrections, warned Hermel: "If you drop off the edge you don't want to turn the wheel sharply or the back trailer will whip out the other way and you've had it. You've got to get her back nice and gently."

The biggest fear for Hermel is from fellow road users: "I worry about the other roadtrain driver coming towards me," he said. "You just don't know what he's going to do. Some of these guys have been on the road for a long time, they're tired and may not have seen anything for miles—I look at their face to see if they'r really awake."

The searing summer daytime temperatures in Australia (up to 50°C) inevitably take their toll on tyres. "If it's really hot we try and run at night," says Hermel. "Otherwise we stop every 1001cm and check the tyres and bearings. We don't run re-treads and we always carry a tool kit."

The alloy "roo" bar and mesh windscreen guard provide vital protection. A fully grown Red Kangaroo stands 7ft tall and weighs in at over 200kg. Hit it and you're talking major front-end damage. The mesh protects the screen and wipers from rocks and other debris thrown up by other passing roadtrains.

While following Hermel's tanker we noticed another problem unique to roadtrains. With so much wiring to run through the rear tail lights can suffer a significant voltage drop. As a result their brightness is reduced to the extent that they're barely visible in daylight.

The braking regulations covering long vehicles are stringent: "Under the regulations the brakes on a Bdouble must come on and off within one second," says Allan Schwarz of Far Western Agencies.

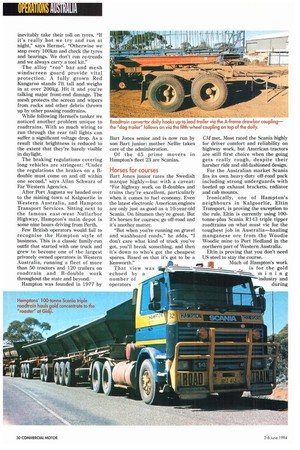

After Port Augusta we headed over to the mining town of Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, and Hampton Transport Services. Sitting next to the famous east-west Nullarbor Highway, Hampton's main depot is some nine hours driving from Perth.

Few British operators would fail to recognise the Hampton style of business. This is a classic family-run outfit that started with one truck and grew to become one of the largest privately owned operators in Western Australia, running a fleet of more than 50 tractors and 120 trailers on roadtrain and B-double work throughout the state and beyond.

Hampton was founded in 1977 by Bart Jones senior and is now run by son Bart junior: mother Nellie takes care of the administration.

Of the 45 prime movers in Hampton's fleet 23 are Scanias.

Horses for courses

Bart Jones junior rates the Swedish marque highly—but with a caveat: "For highway work on B-doubles and trains they're excellent, particularly when it comes to fuel economy. Even the latest electronic American engines are only just as good as a 10-year-old Scania. On bitumen they're great. But it's horses for courses; go off-road and it's another matter.

"But when you're running on gravel and washboard roads," he adds, "I don't care what kind of truck you've got, you'll break something, and then it's down to who's got the cheapest spares. Based on that it's got to be a Kenworth."

That view was echoed by a number of operators CM met. Most rated the Scania highly for driver comfort and reliability on highway work, but American tractors are still first choice when the going gets really rough, despite their harsher tide and old-fashioned design.

For the Australian market Scania fits its own heavy-duty off-road pack including strong underguards with beefed up exhaust brackets, radiator and cab mounts.

Ironically, one of Hampton's neighbours in Kalgoorlie, Eltin Transport, is proving the exception to the rule. Eltin is currently using 100tonne-plus Scania R143 triple tipper roadtrains on what must vie for the toughest job in Australia—hauling manganese ore from the Woodie Woodie mine to Port Hedland in the northern part of Western Australia.

Eltin is proving that you don't need US steel to stay the course.

Much of Hampton's work is for the gold industry and during two days in Kalgoorlie we hitched a ride with two of Hampton's trains on gold mine work. Dave O'Brien's R112 330, with almost a million kilometres under its belt, was delivering water to a nearby gold processing plant. Despite its age the well-worn eightlegger proved a willing worker. O'Brien has been driving roadtrains since 1986: "With 80 tonnes on board you've got to drive way ahead of yourself," he says.

Strai9ht as a die

Despite the potentially unstable nature of a triple roadtrain, according to O'Brien: "ff you set it up well it will run as straight as a die".

In the outback drivers need to be part-mechanic and totally self-reliant. "It's not the sort of country to be in if you're scared to have a go," says O'Brien. "In some parts you might not see anyone for a day."

Any deadtime is put to good use: for O'Brien that means greasing the outfit and checking the tyres.

Outside Kalgoorlie at the town's roadtrain assembly point we joined Graham Calloway, whose R143-450 was pulling three trailers loaded with gold concentrate to the local Gidji "roaster".

All up the Scania roadtrain tipped the scales at 100 tonnes. In place of the usual Scania synchro box the R143 had an 18-speed Fuller. "It's a good truck for the job" reckons Calloway, who appreciates the comfort of the cabover Swede.

On a deserted stretch of road Calloway demonstrated the whip effect on the third trailer: his small twitch of the wheel was amplified as it went down the rig and was clearly visible in the mirrors.

Compared with their UK counterparts Australian drivers in the outback work significantly longer hours and it's likely to stay that way, as one owner-driver we spoke to explained: "It's difficult to see how you could bring down drivers hours. In places like Western Australia; much of the freight we carry is high priority. Start taking longer and you'll start affecting efficiency."

I— by Brian IVeatherley