Costing for Farm Haulage

Page 96

Page 99

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

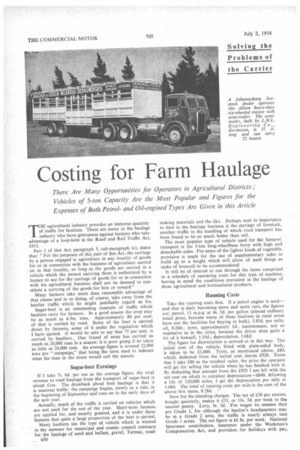

There Are Many Opportunities for Operators in Agricultural Districts ,• Vehicles of 5-ton Capacity Are the Most Popular and Figures for the Expenses of Both Petroland Oil-engined Types Are Given in this Article

THE agricultural industry provides an immense quantity of traffic for hauliers. There are many in the haulage industry who have grievances against farmers who take advantage of a loop-hole in the Road and Rail Traffic Act, 1933.

Part 1 of that Act, paragraph 5, sub-paragraph (c), states that: "For the purposes of this part of this Act, the carriage by a person engaged in agriculture in any locality of goods for or in connection with the business of agriculture carried on in that locality, so long as the goods are carried in a vehicle which the person carrying them is authorized by a licence to use for the carriage of goods for or in connection with his agricultural business shall not be deemed to constitute a carrying of the goods for hire or reward."

Many farmers take more than reasonable advantage of that clause and in so doing, of course, take away from the haulier traffic which he might justifiably regard as his.

Sugar-beet is an outstanding example of traffic which hauliers carry for farmers. In a good season the crop may be as much as 4.5m. tons. Approximately 80 per cent. of that is carried by road. Some of the beet is carried direct by farmers, some of it under the regulation which I have quoted. It would be safe to say that 75 per cent. is carried by hauliers. One friend of mine has carricd as much as 26,000 tons in a season: it is poor going if he takes as little as 20,000 tons. An average figure is around 22,000 tons per "campaign," that being the term used to indicate what the man in the street would call the season.

Sugar-beet Earnings

If I take 75. 6d. per ton as the average figure. the total revenue to road haulage from the transport of sugar-beet is about ilm. The drawback about beet haulage is that it is seasonal traffic; the campaign begins, slowly as a rule, in the beginning of September and runs on to the early days of the new year.

Actually, much of the traffic is carried on vehicles which are not used for the rest of the year. Short-term licences are applied for, and usually granted, and it is under these licences that quite a large proportion of the beet is carried.

Many hauliers use the type of vehicle which is wanted in the summer for municipal and county council contracts for the haulage of sand and ballast, gravel, Tarmac, road a50 making materials and the like. Perhaps next in importance to beet in the haulage business is the carriage of livestock, another traffic in the handling of which road transport has been found to be so much better than rail.

The most popular type of vehicle used for the farmers' transport is the 5-ton long-wheelbase lorry with high and detachable sides. For some of the lighter kinds of vegetable, provision is made for the use of supplementary sides to build up to a height which will allow of such things as sacks of broccoli to be accommodated.

It will be of interest to run through the items comprised in a schedule of operating costs for this type of machine, having in mind the conditions prevalent in the haulage of these agricultural and horticultural products.

Running Costs

Take the running costs first. If a petrol engine is used— and that is daily becoming more and more rare, the figures are: petrol, 13 m.p.g. at 4s. 2d. per gallon (almost ordinary retail price, because many of these hauliers in rural areas have not the facilities for buying in bulk), 3.85d. per mile; oil,. 0.20d.; tyres, approximately Id.; maintenance, not so expensive as in the cities, because the driver does quite a lot of it himself, 1.55d.; depreciation, 168d.

The figure for depreciation is arrived at in this Way. The initial cost of the vehicle, fitted with plain-sided body, is taken to be £1,000. Tyres, as mentioned above, £80, which, deducted from the initial cost, leaves £920. From that I take £80 as the residual value, the price the operator will get for selling the vehicle when he has finished with it. By deducting that amount from the £920 I am left with the net cost on which to calculate depreciation—£840. Allowing a life of 120,000 miles, I get the depreciation per mile at I.68d. The total of running costs per mile is the sum of the above five items, 8.28d.

Now for the standing charges. The tax of £30 per annum, bought quarterly, makes it £33, or 13s. 3d. per week to the nearest penny. Levy, 3s. 3d. For wages we assume they are Grade 1, for although the haulier's headquarters may be in a Grade 2 area, the traffic is nearly always into Grade 1 areas. The net figure is £6 8s. per week. National Insurance contribution, insurance under the Workmen's Compensation Act, and provision for holidays with pay,

amount altogether to 12s. per week. For garage rent. 5s.; vehicle insurance, £1; interest on first cost at 4 per cent. on the initial outlay of £1,000, £40 per annum or 16s. per week. The total is £9 17s. 6d.

Even the owner-driver has to make some provision for establishment costs, but 1 think 30s. per week will cover that item. The total of fixed charges is thus £11 75. 6d.

The corresponding figures for an oil-engined vehicle will approximate to the following: Running costs: fuel, 20 m.p.g. at 3s. 91d. per gallon, 2.25d.: lubricants, 0.20d.; tyres, 1.00d.: maintenance, 1.40d. (it is generally agreed that the maintenance cost of an oil engine is less than that of a petrol engine); depreciation. 1.88d. To arrive at this figure for depreciation I assumed the first cost of the oiler to be £1,300. I deduct £80 for a set of tyres, leaving £1,220 and 1120 as residual value, leaving £1,100. I allow a longer life for the oiler because experience has shown that such an assumption is in accordance with users' experience, and take 140,000 miles as a fair expectation of life. That makes the depreciation 1.88d. The total of running costs of the oiler is shown to be 6.73d. per mile.

In only one item do the standing charges of the oiler iiffer from those of the petrol-engined vehicle, namely.

terest. This, at 4 per cent. on the initial outlay, amounts £52 per annum, which is equivalent to £1 Is. per week. le total of standing charges for the oiler is thus £11 12s. 6d. Now to turn those figures to advantage by trying to scss the rates which the haulier should charge his custoers. Before getting too deeply involved in that matter, me emphasize that there are usually back loads in this partment of the haulage business. The big snag is that ite often there is not a full load in either direction. For ample. the collection of poultry and the delivery of the • ds to central markets is an important branch of agricul • al business in many parts of the country. There are quently, in connection with this class of work, partial :k loads of meal and feeding stuffs, as well as other ming requisites.

)(I this class of work it is quite customary for fairly long ekly mileages to be covered, from 600 to 1,000, and, in case within my knowledge, 1,400 miles per week.

N. day's work covering 120 miles should bring the operator total revenue based on the above figures plus profit. fair profit ratio should be at the rate of 20 per cent. on t. Referring to the figures already given for a petrolined vehicle, £11 7s. 6d. per week is the cost, equivalent is. 3d. per hour for fixed costs and 8.28d. per mile. Add profit percentage of 20 and we get 6s. 4d. as the charge hour and 10d. as the charge per mile.

he day's work mentioned above should therefore bring a revenue of £2 10s. 8d. for time and 15 for mileage: I £7 10s. 8d. The amount necessary to cover costs, uding provision for establishment costs, will be eight rs at 5s 3d. which is £2 2s, plus 120 miles at 8.28d. !s. 10d. The total is £6 4s, 10d.

hese two, totals are important to the haulier. They cate the margin of profit which, it should be noted, is • £1 5s. 10d. per day. No one can call that excessive. the day's work covers 180 miles, the figures become £2 2s. per eight-hour day, plus 180 times 8.28d., which is £.6 4s. 3d. Total £8 6s. 3d. His revenue, if he works to my figures, will be £2 10s. 8d. for the eight-hour day plus 180 miles at 10d. per mile, which is £7 10s. The total is £10 Os. 8d. That allows a net profit of £1 14s. 8d.

Any haulier who is engaged in this class of work, knowing his revenue, should set it against these figures if he wishes to know whether he will eventually find himself in difficulties or whether he is really making a profit.

There is a fairly substantial amount of road haulage of artificial manures from town to country. Sometimes this traffic comes as a part or full back load from poultry haulage, or in connection with other transport. More often, however, the distribution is over short distances. Hauliers are generally asked to quote for 1-6 tons over distances of 1-20 miles. The material is in sacks and a fair average period for loading and unloading is 15 min. per ton for each operation. That period applies, of course, when there is no provision for loading from a chute and where no help is given to the driver.

Most of the loads offered are within the 5-ton limit, so that the figures quoted above as the basis of charges are applicable. The minimum profitable rate must be calculated at the rate of 6s. 4(1. per hour plus 10d. per mile, compared with the basic cost of 5s. 3d. per hour and 8.28d. per mile.

Take first the case of a full load on a 5-tonner and a minimum radius of a mile. The time occupied will be 1 hr. 45 min. and the charge for that at 6s. 4d. per hour must be not less

than I Is. Id., to which must be added for the two miles at 10d. which is Is. 8d. (two miles-one each way). The total is 12s. 9d., or 2s. 60. per ton for the first mile lead.

Each addition of one mile to the minimum of one mile lead means that a further six minutes have to be paid for. The charge is 6s. 4d. so that the charge for the time engaged in this second mile lead is 71d. plus Is. 8d. for the two miles actually run, over and above the original one. The additional cost is 2s. 3&d. per 5 tons carried, that is 51d. per ton.

Each additional mile lead for the first few miles calls for the same addition to the charge for the previous one, namely, Sid. per ton.

Over five miles the time per extra mile can be reduced somewhat as there is the opportunity of speeding up a little, and for each successive mile above five it can he taken as five minutes instead of six, thus costing Is. 8d. for travelling plus 6id. for time, making 2s. 2-1d. per vehicle-mile, or 5.id. per ton.

Turning now to the oiler, the corresponding data of costs are calculated from the figures for cost set out above, with, as in the case of the petrol engine, an addition of 20 per cent. for profit. The time and mileage figures arc 6s. 5d. per hour and 8d. per mile. For a day's work involving 120 miles of running and taking up the full eight hours, the charge should be £2 11 s. 4d. for time, plus 120 times 8d. for mileage.

That is :EA, and the total rate can be £6 Ifs. 4d. This compares with the recommended charge for the petrol lorry, 17 10s. 8d. There is in those figures ample food for thought for the haulier who is considering what to charge for work which is offered. tie can either use the oiler and charge according to the relevant figures. or he can use the oiler hut charge according to the figures for petrol. In the latter case he will make an extra profit of about if ,a day S.T.R. 1353