Village people

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

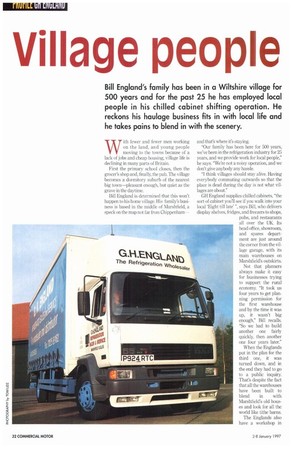

Bill England's family has been in a Wiltshire village for 500 years and for the past 25 he has employed local people in his chilled cabinet shifting operation. He reckons his haulage business fits in with local life and he takes pains to blend in with the scenery.

With fewer and fewer men working on the land, and young people moving to the towns because of a lack of jobs and cheap housing, village life is declining in many parts of Britain.

First the primary school closes, then the grocer's shop and, finally, the pub. The village becomes a dormitory suburb of the nearest big town—pleasant enough, but quiet as the grave in the daytime.

Bill England is determined that this won't happen to his home village. His family's business is based in the middle of Marshfield, a speck on the map not far from Chippenham

and that's where it's staying.

"Our family has been here for 500 years, we've been in the refrigeration industry for 25 years, and we provide work for local people," he says. "We're not a noisy operation, and we don't give anybody any hassle.

"I think villages should stay alive. Having everybody commuting outwards so that the place is dead during the day is not what villages are about."

Gil England supplies chilled cabinets, "the sort of cabinet you'll see if you walk into your local 'Eight till late' ", says Bill, who delivers display shelves, fridges, and freezers to shops, pubs, and restaurants all over the UK. Its head office, showroom, and spares department are just around the corner from the village garage, with its main warehouses on Marshfield's outskirts.

Not that planners always make it easy for businesses trying to support the rural economy. "it took us four years to get planning permission for the first warehouse and by the time it was up, it wasn't big enough," Bill recalls. "So we had to build another one fairly quickly, then another one four years later."

When the Englands put in the plan for the third one, it was turned down, and in the end they had to go to a public inquiry. That's despite the fact that all the warehouses have been built to blend in with Marshfield's old houses and look for all the world like tithe barns.

The Englands also have a workshop in Colerne, the next village, which their engineers use when they're repairing fridges.

"My dad was in agricultural haulage—cattle feed and so on—during the fifties and sixties, so we've always had lorries. I grew up with them, and I've driven them myself" Bill says.

"The difference now is that we use our own trucks to distribute the products we sell. Before, we were hauling for other people."

Most of the refrigeration equipment is imported from Europe. "We sell some British products too, but to be perfectly honest—and I hate to say this—it seems harder and harder to find British companies who will listen to what the customer wants, and will make what we can sell," says Bill.

The Englands run their own vehicles because they want total control over their delivery schedules, and maximum flexibility Their drivers are well-used to handling the cargo, and damage claims are rare.

In charge

"Because we're in charge, we can be as flexible as the customer wants us to be," he says. "If we were to use carriers we'd be in someone else's hands, and they wouldn't go a hundred miles out of their way to make a drop.

"We will because to us it's part of the service we supply" Bill and his family—his dad George, son Ben, and Bill's wife Jenny all work in the business—run 11 commercial vehicles altogether, and the largest is only a 12-tonner.

"Remember that a lorry load of fridges doesn't weigh that much," says Bill. "You're talking a lot of volume, but very little weight."

The line-up consists of a Leyland Daf 55 Series at 12 tonnes—it arrived in November— plus a trio of Freighters at 11 tonnes apiece.

"We've run Leylands for over 20 years," he says. "In fact I used to drive a Boxer myself, and that was a hideous machine. But nowadays they're very good, they're quiet, and they're reliable.

"Our oldest Freighter is G-registered, it's done 530,000 miles, and it's still on its original engine. If you can get that sort of work out of them, you're getting your money's worth; and if you do get any trouble, Leyland Dafaid is absolutely brilliant."

They're supported by a quartet of 3.5-tonners—a pair of LIN Convoys and two 400 Series models from the same manufacturer— plus a couple of LDV 200s and an old Sherpa used by the outfit's mobile engineers. A Morris Commercial from the twenties is the mascot, and is still a runner.

The 55 Series and the Freighters are used for long-distance delivery and installation work, covering around 90,000 miles a year.

"The business has changed over the years," Bill reflects.

"A few years ago we delivered to warehouses, and the customer would transport the products to the end-user himself. But now they want them taken directly to the shops etc that will he using them."

All equipped with full-width tuckaway taillifts, the trucks are invariably double-manned because it takes two people to unload, say, a chilled cabinet, manoeuvre it on to the premises on a set of portable bogies, and place it exactly where the customer wants it.

-A big display case for a shop can weigh 8cwt," says Bill. "We use near-maximumlength rigids, with 25ft bodies for an overall length of 31ft; I'm sorry, but I've not gone metric yet," he continues.

"If we went any bigger than that, which we would by definition if we used artics, then we'd have a hell of a problem getting into a lot of the places we go to. Even with a 12-tonner, it can be difficult.

"We do some jobs for Sainsbury and Gateway, often as a consequence of our supplying the refrigeration company that supplies them, and those are usually easy deliveries. But pubs and restaurants account for 40% of our drops, and with them access can be very awkward, as it can be with 'Eight till lates' and Spar minimarts."

Four years ago the Englands decided to start switching from flatbeds to curtainsiders.

Advantage

"When the speed limiters came in, the advantage of not having any wind resistance behind you when you're empty disappeared," he says. "And we realised too that using curtainsiders rather than roping and sheeting the load would speed up deliveries."

The bodies have timber flooring skinned with steel plate to make it easier to slide the cargo on and off.

They're built by Braces of Bristol, and Del makes the tuckaway tail-lifts which are also fitted to the 3.5-tonners.

The driver and his mate often have to have nights away. "We've always had Freighters with sleeper cabs, and although you can put another bunk across the seats—which is what we've been doing—it doesn't give them a lot of room," Bill explains.

"So when we went for the 55 we decided to specify a production line sleeper-cab plus a cab-top sleeper compartment from Hatchers," he says. 'It gives you a nice big cab that you can stand up in.

"When we went to the 55 Leyland had stopped making the 11-tonner, so we had the 12-tonner instead, which hasn't really made a lot of difference."

The Englands had gone for a 5.5m wheel base previously, which meant a pronounced rear overhang it made them look as though they were loaded when they were empty" says Bill.

"So on the 55 we went for a 6.0-metre wheelbase. It looks nicer, and the wheels are nearer the back," he says.

"They've toughened the chassis up, and they've mounted all the gubbins—the air tanks and so on—in-board," he adds. "That protects them from minor scrapes and bangs."

The 55's 160hp 5.88-litre Cummins engine is currently returning 16mpg. "It's brand-new, of course, so we can expect this figure to improve," says Bill. "We get 15 to 16mpg out of the Freighters, only one of which still has a flatbed body" So what does he think of his LDV Convoys?

"Even though they've got the same Peugeot engines and gearboxes as their predecessors (LDV has only just started to fit Ford Transit boxes), LDV has made them much quieter," he replies. "They represent a step in the right direction.

"We've gone for the turbo-diesels, because the naturally aspirated diesel is a waste of time. I think they should drop it because it leaves you with such a poor impression of the vehicle."

He's stayed loyal to this model through all its various incarnations ever since it was launched in the early eighties. "We've had a few dud ones over the years. The old 350s used to vibrate so much that we had to bolt them back together again every so often, and those Land Rover diesel engines they used to use were always having to be replaced.

"But in our experience LDV quality has got a lot better."

E by Steve Banner