Enasa gears up for

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Spain's projected entry into the EEC will open up potentially large new markets for Enasa the country's largest builder of commercial vehicles. But it will also make its domestic market more accessible to outside manufacturers. Tim Blakemore looks at the investment the company has been making in new plant and equipment to avoid becoming, in the words of its vice president, corporate development, "no more than an assembly line"

THIS YEAR'S Brussels Shaw (CM last week) was the first time Pegaso vehicles have been on display in the heart of the Common Market. That is significant. There could hardly have been a clearer outward sign of their manufacturer's strategy for its survival and future development.

Enasa (Empresa Nacional de Autocamiones Sociedad Anonima), like all manufacturers in Spain's motor industry, is having to face up to the dramatic changes which will result from that country's joining the EEC. From 1986, the projected year of entry, the high import tariffs (typically 40 per cent on vehicle products) which were introduced in General Franco's day and which still protect Spanish manufacturers will be progressively phased out. Within a few years Enasa and the domestic market which it presently dominates will be exposed to the full-blooded competition for commercial vehicle sales which all EEC countries are already experiencing.

Enasa's management for some time has been adapting its company to meet the challenge. Though Enasa is by no means one of the giants in lorry building the repercussions from decisions taken in Madrid are spreading further and further afield. The Pegaso vehicles on display at Brussels and the newly-established dealer network which supports them is one example. Last year's purchase of Seddon Atkinson from International Harvester is another which more directly affected British operators.

Then there is the Cabtech agreement which Enasa and Daf signed last year for the sharing of development costs of a new cab and, more recently, came the news that General Motors was interested in buying a substantial share of Enasa.

All these events fit nicely into a framework for the development in the late Eighties of a "medium-sized commercial vehicle manufacturer" proposed by Juan Llorens Carrio, Enasa's vice-president corporate development, at a conference in London as long ago as November 1983.

He spoke of following the path of "corporate independence backed up by collaboration with other companies, limited to projects whose development or investment costs would make them attractive propositions."

During a recent visit to Spain I was able to see how Enasa is progressing along its chosen path. I was particularly interested in the subject of research and development, which was described by Senor Llorens as "the Achilles heel for most medium-sized companies."

Senor Llorens said that any company of Enasa's size (it builds around 15,000 vehicles of all types a year) can no longer afford the high research and development costs for all or even most of its own components.

"It has to stop designing components and instead buy them or manage to come to agreements on licensed manufacturing," he said. But he was cautious about taking that argument too far. "This line of logic cannot be taken to the extremes of transforming the company into no more than an assembly line, with neither

character nor technology of its own."

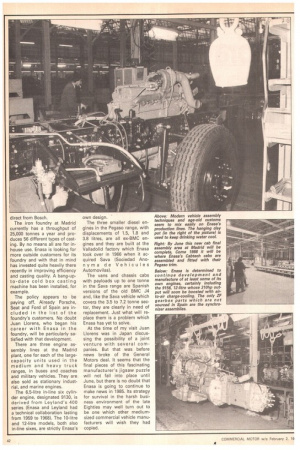

My visit to two of Enasa's three plants in Spain provided clear evidence that the company has no intention of becoming "no more than an assembly line". At the Barcelona plant on Spain's north-east coast some Pta 1.5bn (£7.5m) has been spent on a new technical centre. The first phase was completed last June when the engineers and designers who work on all Enasa trucks and buses (but not military vehicles) and on all components (except engines which have a department of their own), moved into a new building.

A new fatigue testing laboratory with Carl Schenk electro-hydraulic test rigs mounted on a floor which is isolated from the building has also been commissioned.

Most design work in Barcelona is still done on drawing boards in the long-established manner, but Enasa is very keen to keep up with modern computer technology and has begun to install a CAD (computer aided design) system.

Seven terminals, including one Techtronics with colour graphics for use on finite element analysis, were installed at the time of my visit. The introduction of many more is planned as the computer's database grows. At present it holds about half of all Enasa's new drawings. There is no doubt that, if by June this year the negotiations with General Motors are completed successfully as expected, then the installation of CAD and CAM systems at Enasa will gather even more pace.

GM's own enthusiasm for computer-aided design and manufacture of commercial vehicles (described in CM, October 27, 1984) is well matched by that of the engineer, Senora Lourdes Plana Sanz, who is in charge of the CAD project at Barcelona.

The man who heads the whole of Enasa's engineering department is Gabriel Perez Castillo. In his new post he is aiming to achieve similar improvements in efficiency to those for which he was recently responsible as manager at the Madrid plant.

His staff, which currently totals 472, is divided into four sections: truck design; vehicle development; bus and components design; and engine engineering. In addition there are two subsidiary sections called "advanced concepts" and "special projects."

None of the design work for the new Daf/Enasa cab is being done in Spain, though eventually half the cab panels will be pressed there. There will not be any duplication of tooling. A team of Enasa engineers is now working with its Dutch counterparts at the Cabtech design office at Eindhoven.

It seems illogical that when Enasa's head office and main plant is in Madrid, the Spanish capital, the company's research and development centre should be nearly 500km away at Barcelona. The location of the technical centre is partly explained by Enasa's history. The company was founded in 1946 at the Bar celona factory, where Hispano Suiza cars had been built. Also, the city's university has a tradition of producing Spain's finest engineers and scientists.

Furthermore, Barcelona is a main port for Enasa's exports, which currently account for about 46 per cent of its total sales and are growing. So having a plant there gives it a useful flexibility. For example, the 11,800, model 3046/10 4x4 atvs (all terrain vehicles) which Enasa is supplying to Egypt following the one billion dollar contract signed last year, are being assembled minus their cabs at Madrid, where the mili tary division is based, Their cabs are being fitted at the Barcelona plant en route to the port.

Despite a cutback in the number of employees at Barcelona over the past 12 months from 3,000 to 2,350, it still has spare capacity. This plant's main function is manufacturing Pegaso front and rear axles and the ZF gearboxes which are built under licence. These are now used exclusively throughout the Pegaso truck range.

This ZF/Enasa venture is another good example of strategy to which Juan Llorens referred in 1983. The gearboxes are not "just assembled" by Enasa. If they were the company would have to pay a 4C per cent import tariff on all gearbox components coming from Germany.

Enasa machines the gear sets and shafts. Gearbox casings, Loo,are made in Spain. Only the synchronisers are imported.

At Enasa's Madrid premises, where the company has some 5,500 employees, there is yet more evidence of adaptation the anticipating Spain's entry into the EEC, some areas have been slimmed down, others have had new investment. The company's own fuel pump shop at Madrid currently employs about 500, building Bosch inline and rotary pumps under licence for the Pegaso range of diesel engines with capacities from 1.5 to 12 litres. It is highly likely that by 1986 this fuel pump shop will be closed, for by then it will make more economic sense to buy fuel pumps direct from Bosch.

The iron foundry at Madrid currently has a throughput of 25,000 tonnes a year and produces 56 different types of casting. By no means all are for inhouse use. Enasa is looking for more outside customers for its foundry and with that in mind has invested quite heavily there recently in improving efficiency and casting quality. A bang-upto-date cold box casting machine has been installed, for example.

The policy appears to be paying off. Already Porsche, Seat and Ford of Spain are included in the list of the foundry's customers. No doubt Juan Llorens, who began his career with Enasa in the foundry, will be particularly satisfied with that development.

There are three engine assembly lines at the Madrid plant, one for each of the largecapacity units used in the medium and heavy truck ranges, in buses and coaches and military vehicles. They are also sold as stationary industrial, and marine engines.

The 6.5-litre in-line six cylinder engine, designated 9130, is derived from Leyland's 400 series (Enasa and Leyland had a technical collaboration lasting from 1959 to 1968). The 10-litre and 12-litre models, both also in-line sixes, are strictly Enasa's own design.

The three smaller diesel engines in the Pegaso range, with displacements of 1.5, 1.8 and 3.8 litres, are all ex-BMC engines and they are built at the Valladolid factory which Enasa took over in 1966 when it acquired Sava (Sociedad Anonyma de Vehicules Automovilas).

The vans and chassis cabs with payloads up to one tonne in the Sava range are Spanish versions of the old BMC J4 and, like the Sava vehicle which covers the 3.5 to 7.2 tonne sector, they are clearly in need of replacement. Just what will replace them is a problem which Enasa has yet to solve.

At the time of my visit Juan Llorens was in Japan discussing the possibility of a joint venture with several companies. But that was before news broke of the General Motors deal. It seems that the final pieces of this fascinating manufacturer's jigsaw puzzle will not fall into place until June, but there is no doubt that Enasa is going to continue to make news in 1985. Its strategy for survival in the harsh business environment of the late Eighties may well turn out to be one which other mediumsized commercial vehicle manufacturers will wish they had copied.