OPERATIT

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

G COSTS

OF LA GEI MACHINES

IfN an article last month certain figures were quoted as a basis for calculating remunerative charges to be made for the charter of what may reasonably be described as the smallest type of aeroplane which is suitable for this class of work, namely, the machine for two or three passengers. A considerable proportion of the charter work which is carried on in this country is in connection with machines of that type. It is proposed now to discuss average costs of operating machines for five to seven passengers, such as are becoming popular for both charter and schedule flights.

A five-seven passenger machine may cost in the first place anything from £2,000 to £4,500, and as an average figure we may take £3,300. For this a British multiengined cabin aeroplane can be purchased, capable of a cruising speed of at least 100 m.p.h. Speeds are increasing and 100 m.p.h. is certain to be out of date before long, but it is a speed that will serve as a practical basis for operating costs o`,. the present time.

For a machine of this type having a normal fuel-tank range and a pay-load capacit9 which allows a reasonable margin for luggage as well as the five or more passengers, a petrol consumption at the rate of about 14 gallons per hour, or 7 m.p.g. may be taken as an average figure.

The preliminary procedure inseparable from all calculations of profitable fares is the actual cost of the machine itself. The items of cost naturally fall into two categories, those which are unaffected by the distance covered annually and those dependent upon that distance.

In the former class come depreciation, interest on first cost, insurance, aerodrome and landing fees, licences and, with certain qualifications in particular cases, wages. For the convenience of such a calculation as that which we are about to make it may be assumed that wages are

B32 a standing charge not normally affected by the hours of flight. That would more usually be the case whenever a machine was regularly employed week in and week out throughout the year, and that is the class of use we are considering. The running costs are the expenditure on petrol, oil and maintenance.

A brief word is necessary in reference to depreciation, for this item, in respect of aircraft, has a special significance. Depreciation in the ordinary sense of the term, as has already been explained in the articles on costing which preceded this series on charges, has no meaning in connection with aeroplanes. The care and efficiency with which aeroplanes must by law be maintained has this result. In figures of cost, however, cognizance has to be taken of the factor of obsolescence.

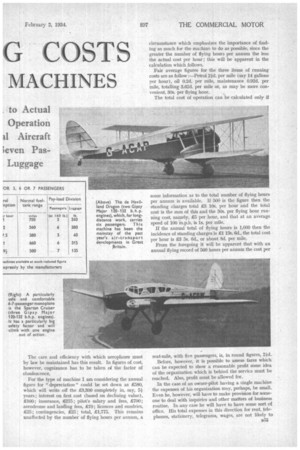

For the type of machine I am considering the annual figure for " depreciation " could be set down as £580, which will write off the £3,300 completely in, say, 5/ years ; interest on first cost (based on declining value), £100; insurance, £275; pilot's salary and fees, £700; aerodrome and landing fees, £70; licences and sundries, £25; contingencies, £25; total, £1,775. This remains unaffected by the number of flying hours per annum, a circumstance which emphasizes the importance of finding as much for the machine to do as possible, since the -greater the number of flying hours per annum the less the actual cost per hour ; this will be apparent in the calculation which follows.

Fair average figures for the three items of running costs are as follow :—Petrol 21d. per mile (say 14 gallons per hour), oil 0.2d. per mile, maintenance 0.92d. per mile, totalling 3.62d. per mile or, as may be more convenient, 30s. per flying hour.

The total cost of operation can be calculated only. if some information as to the tcital number of flying horns per annum is available. If 500 is the figure then the standing charges total £3 10s. per hour and the total cost is the sum of this and the 30s. per flying hour running cost, namely, £5 per hour, and that at an average speed of 100 m.p.h. is Is. per mile.

If the annual total of flying hours is 1,000 then the incidence of standing charges is £1 15s. 6d., the total cost per hour is £3 5s. 6d., or about 8d. per mile.

From the foregoing it will be apparent that with an annual flying record of 500 hours per annum the cost per seat-mile, with five passengers, is, in round figures, 21d. Before, however, it is possible to assess fares which can be expected to show a reasonable profit some idea of the organization which is behind the service must be reached. Also, profit must be allowed for.

In the case of an owner-pilot having a single machine the expenses of his organization may, perhaps, be small. Even he, however, will have to make provision for someone to deal with inquiries and other matters of business routine. In any case he will have to have some sort of office. His total expenses in this direction for rent, telephones, stationery, telegrams, wages, are not likely to average less than £4 or £5 per week. Add, say, £15 per week for profit and the total which may be termed the gross profit is 220 weekly or 1E1,000 per annum.

For purposes of calculation of rates, etc., the foregoing establishment expenses may be treated in the same way as the standing charges.

In the case of business which produces 500 flying hours per annum, for example, this is equivalent to a charge of £2 per hour, bringing the total to £7 per hour, which involves a charge per mile flown of 16.80d. With five passengers that means that, provided (for example) the machine conveys those passengers out and home, a profitable rate will be 3.36d. per passenger per mile.

Of course, if the business be more flourishing and the number of flying hours per annum be 1,000 then the • total will be only £4 5s. per hour, or approximately 10d. per mile; and a fare charge of 2id. per passenger per mile under the above-named conditions will be ample.

With a bigger organization operating several machines the calculation of the establishment costs becomes a matter of greater difficulty. Indeed, it is impossible to indicate in a general article what the figure may be.

Take an organization operating, say, five aeroplanes ; the office expenses would probably total £1,000 to £1,200 per annum. If it still be desired to make £15 profit per week per machine the total from the five is slightly over £8,800 per annum, so that the total gross profit must be £5,000 per annum.

It is, indeed, in connection with establishment costs that careful watch must be kept by operators.