Cool on Cahntaq

Page 22

Page 23

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

UK hauliers have been decidedly cool on cabotage: there are currently more permits than there are applicants to use them. The main demand is not for permits to work overseas, but from hauliers in Northern Ireland who need permits to work in Eire.

Almost four years after the

introduction of cabotage permits,demand from UK hauliers has yet to exceed supply.

The Department of Transport's International Road Freight Service branch, which issues the permits in the UK, defines cabotage as the "undertaking of national haulage in one EC country by a haulier from another".

Since the first quota of 2,214 monthly permits became available in July 1990 there has been a reluctance on the part of many of the UK's internationally bound operators to get involved in what at first appears to be a logical extension to international freight movements. Apart from Irish hauliers, that is.

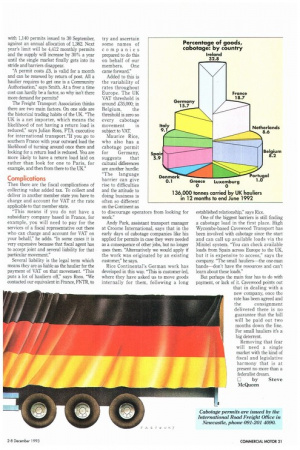

In the period since cabotage was allowed, 1RFS figures show hauliers from Northern Ireland have dominated the number of processed applications. However, a recent government report revealed that of UK applications received in the 12 months to June 1992, 32% of the total 136,000 tonnage carried under permit was carried in the Republic of Ireland.

Demand

Demand for permits to work in other countries is increasing, but Ireland remains way ahead. The next highest demand was for France with 19% followed by Germany with 15%. The remaining 34% was split between the other EC member states with the exception of Luxembourg and Greece where UK hauliers carried no tonnage under cabotage permit.

Sheila McCabe, president of the Irish Road Haulage Association, suggests the reason for Ireland's domination of the cabotage market is the traditional links between Northern Irish hauliers and businesses in the Republic.

Maurice Rice operates Rice Continental, a three-truck group age business based in County Tyrone. He explains that for Northern Irish hauliers, accepting a load from Dublin to Galway is not unlike a Welsh operator accepting a load from London to Leeds. The difference is that the Welsh operator needs no cabotage permit.

"Once your vehicle has tipped in Dublin after a journey from the Continent," he says, you are inevitably looking for a load with a good rate to Limerick from where you can get a good rate back to Dublin again. He may well pick up another load in Dublin bound for the Continent again."

Most of our hauliers are well practised in the art of securing the return load to the UK, so the need to obtain a load under the conditions of cabotage may be limited," says Roger Smith, head of the IRFS. His department's figures clearly show the early reluctance of UK hauliers to get involved in cabotage.

Although 2,214 monthly permits were allocated to the UK in the first year of operation (1 July 1990-30 June 1991) only 1,160 were issued. Demand rose in the second year with 2,438 monthly permits available and 2,298 issued. But interest fell again in the six months to 1 January 1993 with 756 applications for 1,340 permits.

This was due to be the last permit period before the free single market but it has been decided that permits will continue to be issued until 1998.

Demand this year has increased again

with 1,140 permits issued to 30 September, against an annual allocation of 1,362. Next year's limit will be 4,412 monthly permits and the supply will increase by 300/h a year until the single market finally gets into its stride and barriers disappear.

"A permit costs £5, is valid for a month and can be renewed by return of post. All a haulier requires to get one is a Community Authorisation," says Smith. At a fiver a time cost can hardly be a factor, so why isn't there more demand for permits?

The Freight Transport Association thinks there are two main factors. On one side are the historical trading habits of the UK. "The UK is a net importer, which means the likelihood of not having a return load is reduced," says Julian Ross, FTA executive for international transport."If you go to southern France with your outward load the likelihood of turning around once there and looking for a return load is reduced. You are more likely to have a return load laid on rather than look for one to Paris, for example, and then from there to the UK."

Complications

Then there are the fiscal complications of collecting value added tax. To collect and deliver in another member state you have to charge and account for VAT at the rate applicable to that member state.

"This means if you do not have a subsidiary company based in France, for example, you will need to pay for the services of a fiscal representative out there who can charge and account for VAT on your behalf," he adds. "In some cases it is very expensive because that fiscal agent has to accept joint and several liability for that particular movement."

Several liability is the legal term which means they are as liable as the haulier for the payment of VAT on that movement. ''This puts a lot of hauliers off," says Ross. "We contacted our equivalent in France, FNTR, to try and ascertain some names of companies prepared to do this on behalf of our members. One came forward."

Added to this is the variability of rates throughout Europe. The UK VAT threshold is around £35,000; in Belgium, the threshold is zero so every cabotage movement is subject to VAT Maurice Rice, who also has a cabotage permit for Germany, suggests that cultural differences are another hurdle: "The language barrier can give rise to difficulties and the attitude to doing business is often so different on the Continent as to discourage operators from looking for work."

Andy Park, assistant transport manager at Croome International, says that in the early days of cabotage companies like his applied for permits in case they were needed as a consequence of other jobs, but no longer uses them. "Alternatively we would apply if the work was originated by an existing customer," he says.

Rice Continental's German work has developed in this way. "This is customer-led, where they have asked us to move goods internally for them, following a long established relationship," says Rice.

One of the biggest barriers is still finding a cabotage load in the first place. High Wycombe-based Cavewood Transport has been involved with cabotage since the start and can call up available loads via the Minitel system. "You can check available loads from Spain across Europe to the UK, but it is expensive to access," says the company. "The small hauliers—the one-man bands—don't have the resources and can't learn about these loads."

But perhaps the main fear has to do with payment, or lack of it. Cavewood points out that in dealing with a new company, once the rate has been agreed and the consignment delivered there is no guarantee that the bill will be paid out two months down the line. For small hauliers it's a big deterrent.

Removing that fear will need a single market with the kind of fiscal and legislative harmony that is at present no more than a federalist dream.

by Steve McQueen