HUMBERT!

Page 108

Page 109

Page 110

Page 127

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

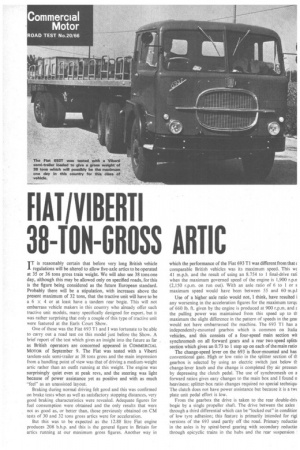

38-TON-GROSS ARTIC

IT is reasonably certain that before very long British vehicle regulations will be altered to allow five-axle allies to be operated at 35 or 36 tons gross train weight. We will also see 38 tons one day, although this may be allowed only on specified roads, for this is the figure being considered as the future European standard. Probably there will be a stipulation, with increases above the present maximum of 32 tons, that the tractive unit will have to be a 6 X 4 or at least have a tandem rear bogie. This will not embarrass vehicle makers in this country who already offer such tractive unit models, many specifically designed for export, but it was rather surprising that only a couple of this type of tractive unit were featured at the Earls Court Show.

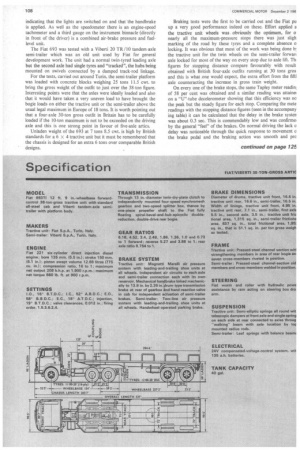

One of these was the Fiat 693 Ti and I was fortunate to be able to carry out a road test on this model just before the Show. A brief report of the test which gives an insight into the future as far as British operators are concerned appeared in COMMERCIAL MOTOR of September 9. The Fiat was tested with a Viberti tandem-axle semi-trailer at 38 tons gross and the main impression from a handling point of view was that of driving a medium-weight artic rather than an outfit running at this weight. The engine was surprisingly quiet even at peak revs, and the steering was light because of power assistance yet as positive and with as much "feel" as an unassisted layout.

Braking during normal driving felt good and this was confirmed on brake tests when as well as satisfactory stopping distances, very good braking characteristics were revealed. Adequate figures for fuel consumption were obtained and the only results that were not as good as, or better than, those previously obtained on CM tests of 30 and 32 tons gross artics were for acceleration.

But this was to be expected as the 12.88 litre Fiat engine produces 208 b.h.p. and this is the general figure in Britain for artics running at our maximum gross figures. Another way in

which the performance of the Fiat 693 Ti was different from that ( comparable British vehicles was its maximum speed. This wk. 41 m.p.h. and the result of using an 8.754 to 1 final-drive rati when the maximum governed speed of the engine is 1,900 r.p.n (2,150 r.p.m. on run out). With an axle ratio of 6 to 1 or s maximum speed would have been between 55 and 60 rn.p.I Use of a higher axle ratio would not, I think, have resulted i any worsening in the acceleration figures for the maximum torgt of 660 lb. ft. given by the engine is produced at 900 r.p.m. and k. the pulling power was maintained from this speed up to th maximum the slight difference in the pattern of speeds in the geal would not have embarrassed the machine. The 693 Ti has a independently-mounted gearbox which is common on Italia vehicles, and this consists of a four-speed main section wii synchromesh on all forward gears and a rear two-speed splith section which gives an 0.73 to 1 step up on each of the main ratio

The change-speed lever on the 693 is floor-mounted and has conventional gate. High or low ratio in the splitter section of th gearbox is selected by using an electric switch just below th change-lever knob and the change is completed (by air pressurl by depressing the clutch pedal. The use of synchromesh on a forward ratios gives easy changes to the main box and I found n heaviness; splitter-box ratio changes required no special techniqul The clutch does not have power assistance but because it is a tw{ plate unit pedal effort is low.

From the gearbox the drive is taken to the rear double-driA bogie by a single propeller shaft. The drive between the axles through a third differential which can be "locked out" in conditior of low tyre adhesion; this feature is primarily intended for rigi versions of the 693 used partly off the road. Primary reductio in the axles is by spiral-bevel gearing with secondary reductio through epicyclic trains in the hubs and the rear suspension 1y a two-spring system. The axles are connected by rigid beams &Hied to the underside of the casings on both sides and the centres ,f the beams are connected to the centres of the springs. Centrally)cated radius-rods above the axles complete their location. The ront ends of the springs are fixed while the rear ends are slipperaounted in brackets designed to give a degree of variable rate.

In general the design of the Fiat 693 is very robust and a lot if attention is paid to detail, particularly where there is a prospect if giving increased life. Good examples of this are the provisions aade for filtration on the engine—air, oil and fuel. There is a arge size oil-bath-type air-intake filter, a pair of cartridge-type hers for engine lubricating oil and a good-sized filter of the same ype for fuel.

The same applies to brakes. There are completely independent jr-pressure circuits for each of the axles and for the semi-trailer ?Inch gives a good measure of safety in the event of a failure. The iesign does not include a completely independent secondary ystem, but now that "split" systems like that on the Fiat can be Lsed on all classes of vehicle to meet the main and secondary brake equirements it is possible that the layout will be acceptable in lritain as it stands.

Although there are four separate circuits on the 693 the pipevork is relatively uncomplicated and this is largely due to the use if a Magneti Marelli valve-and-distributor brake unit. The main ulves are contained in this which results in the pipework to the xles being quite simple.

Visitors to the Fiat stand at the Commercial Motor Show will -ouch for the high standard of cab construction and furnishing in the Fiat design. It was a very comfortable vehicle to drive and Ivishly equipped with switches, warning lights and so on. There re 10 warning lights—for water temperature, oil pressure. brake iressure, generator, indicators and so on, and there is also one for

indicating that the lights are switched on and that the handbrake is applied. As well as the speedometer there is an engine-speed tachometer and a third gauge on the instrument binnacle (directly in front of the driver) is a combined air-brake pressure and fuellevel unit.

The Fiat 693 was tested with a Viberti 20 TR /10 tandem-axle semi-trailer which was an old unit used by Fiat for general development work. The unit had a normal twin-tyred leading axle but the second axle had single tyres and "tracked", the hubs being mounted on swivels connected by a damped track-rod linkage.

For the tests, carried out around Turin, the semi-trailer platform was loaded with concrete blocks weighing 25 tons 11.5 cwt to bring the gross weight of the outfit to just over the 38-ton figure. Interesting points were that the axles were ideally loaded and also that it would have taken a very uneven load to have brought the bogie loads on either the tractive unit or the semi-trailer above the usual legal maximum in Europe of 18 tons. It is worth pointing out that a four-axle 30-ton gross outfit in Britain has to be carefully loaded if the 10-ton maximum is not to be exceeded on the driving axle and this is one strong point in favour ol five-axle artics.

Unladen weight of the 693 at 7 tons 8.5 cwt. is high by British standards for a 6 X 4 tractive unit but it must be remembered that the chassis is designed for an extra 6 tons over comparable British designs.

Braking tests were the first to be carried out and the Fiat pu up a very good performance indeed on these. Effort applied a the tractive unit wheels was obviously the optimum, for a nearly all the maximum-pressure stops there was just sligh marking of the road by these tyres and a complete absence o locking. It was obvious that most of the work was being done b: the tractive unit for the twin wheels on the semi-trailer forwar( axle locked for most of the way on every stop due to axle lift. Th figures for stopping distance compare favourably with result obtained with British four-axle outfits running at 30 tons gros and this is what one would expect, the extra effort from the fiftl axle counteracting the increase in gross train weight.

On every one of the brake stops, the same Tapley meter readin, of .58 per cent was obtained and a similar reading was attainel on a "U"-tube decelerometer showing that this efficiency was ric the peak but the steady figure for each stop. Comparing the mete readings with the stopping distance figures (seen in the accompany ing table) it can be calculated that the delay in the brake syster was about 0.3 sec. This is commendably low and was confirme by the general "feel" of the brakes. On normal driving the lack c delay was noticeable through the quick response to movement c the brake pedal and the braking action was smooth and pre essive. As the Fiat has a transmission handbrake which cannot considered a dynamic brake on a 38-ton outfit no handbrake its were carried out. But later in the day this unit proved to be gable of holding the outfit on a 1 in 6.5 gradient with plenty hand.

It was not possible to find a fuel consumption route in the :inky of Turin with a similar character to those used in Britain. le terrain is either relatively flat or mountainous and the route iosen fell into the former category. The distance covered in coking fuel consumption wag 12.5 miles this being an out-andturn run over a stretch of dual carriageway which contained ily one real gradient in each direction. Because the run was made about 40 m.p.h., or just under the top speed of the test vehicle, e same result would have been obtained on a motorway-type n both in respect of fuel consumption and average speed. The 754 to 1 final-drive ratio in the test vehicle is low by British indards being intended for Italy where much of the country hilly or mountainous. Higher ratios are available and if 6 to 1 id been fitted as is more common in Britain, consumption would irdly have changed for a motorway-type run averaging in the gion of 55 m.p.h. For a test at 40 m.p.h. over the route used insumption would probably have gone up to at least 8 m.p.g. ith a 6 to 1 axle ratio and I would estimate that on the type of • ute used on road tests in Britain the 693 with an axle ratio of is order would have given about 7 m.p.g.

Acceleration figures were something like 20 per cent worse an comparable results obtained for 30/32 ton British outfits sted and would probably have been little changed with a 6 to 1 de ratio as the steps in the eight forward gears are very close

and the torque from the engine peaked at 900 r.p.m. Maximum speeds in the gears were 5, 6.5, 9, 12, 16, 22, 30 and 41 m.p.h.

There would also have been little change in hill climbing ability. On the 1 in 6.5 hill used to check handbrake performance, easy restarts in first-high ratio were made and from the performance there I would accept the Fiat claim that the 693 with 8.754 to 1 ratio has a maximum gradient ability of 1 in 5. With an axle ratio of about 6 to 1 this will be reduced to about 1 in 7 at 38 tons gross and if this is not considered acceptable by UK operators, a ratio of 7 to 1 would give a gradient ability of something like 1 in 6 and maximum speed of about 50 m.p.h.

The hill used for handbrake tests and restart tests—these were accomplished without difficulty when both facing up and facing down the gradient—was fairly short and in a built-up area so it was not possible to do fade tests. But the Fiat is designed for use in country involving descents of three and four miles and resistance to fade will have been a point of considerable attention by the designers of the vehicle. In any case, an exhaust brake is standard on the 693 and the use of this equipment overcomes most of the problems that can be experienced with fade on long hill descents.

Because the Fiat test came up in the middle of one of the busiest times of the year for COMMERCIAL MOTOR—just before the Commercial Show—time available for the test was limited and I had only one day with the vehicle. But this was enough to gain a very favourable impression. I enjoyed driving the outfit which was not as much of a handful as may be expected. Overall length was over 44 ft. but there was no feeling that this was the case or for that matter that a 38-ton outfit was being driven. Manoeuvrability was very good; the tracking axle of the semitrailer resulted in the behaviour being more like that of a shortishwheelbase single-axle unit.

Access to the Fiat cab was easy with the first step height 2 ft. 2 in. and the cab floor 3 ft. 8 in. from the ground, and immediately upon taking over the wheel I felt at home. One of the most impressive aspects of the 693 was the quietness of the engine which even at maximum speed did not prevent normal conversation. Visibility is very good in the Fiat cab and the mirrors are well chosen and well placed.

It is difficult •to comment on maintenance aspects without actually working on a vehicle but the 693 did not appear to have any bad points in this respect and access to the engine and components is very good because the engine cover, which can be removed completely, extends right down to the floor all round the power unit.