IMPORTANT POINTS IN CHASSIS DESIGN.

Page 20

Page 21

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Stability on Wet Surfaces and Under Braking Strains is Still an Attribute of Chass's Design that is Not Generally Attained.

rr HE POWER unit of the commercial vehicle, as was shown in an article in last week's issue specially directed towards this subject, has in recent years undergone more modification than the mere casual observer, content to judge from external appearances, would be able to recognize. Its efficiency from a working point of view and its reliability—a matter which affects the maintenance staff—have certainly improved. A defect from which internalcombustion engines are liable to suffer is the occur rence of a period where vibration is set up, whilst yet another is the prevalence of a knock at certain degrees of compression. We haite heard of periodic vibration difficult to trace being cured by the employment of two light flywheels in place of one heavy one, the two being connected together through powerful springs, which thus imparted a resiliency to the transmission. The use of pistons which have their skirts more or less separated from the heads will often cure a knock that has eluded other efforts to diagnose and cure.

In this article it is intended to treat of certain matters in relation to the design of the chassis, particularly those connected with stability under braking stresses and laterally under steering influences. In these islands it is inevitable that a vehicle should be designed for operation for three quarters of its working life in bad weather and on wet road surfaces, and no effort must-be neglected to make for safety, both to the vehicle and its load and to other users of the road, under a.ny conditions that may be met.

The steering of a heavy commercial motor for long periods at a time is not an easy task, unless a man is very strong, and anything which may tend to increase the effort necessary to steer the wheels is not looked upon with approval by those to whom is entrusted the task of driving such vehicles. With the use of front-wheel brakes, it is necessary that the pivot line should nearly coincide with the point of contact of the tyre with the ground. It is obvious that, unless this-is the ease, there will be a certain tendency for the wheel to hang back when the brake is applied. Were it possible to ensure that both front-wheel brakes are applied with an even retarding force, one would balance the other, and, consequently, there would be no tendency for the brakes to pull the steering wheels out of the

D36

straight line. It is well known, however, that an even braking effect cannot be relied upon, as one drum may he dry, whilst the other may have a trace of lubricant present. In such a case as this, when. the brake is applied a swerve to one side may be expected unless the pivot line is arranged so as to line to the point of contact -with the ground.

This arrangement of the pivot line offers no difficulty when the vehicle is travelling at a good pace, but it makes rna.nceuvring in tight places at slow speeds more difficult, as a certain amount of tyre grinding must take place.

Should Front-wheel Braking Cause Skidding?

In the matter of skidding due to the use of frontwheel brakes, one Inuit not rely upon experience gained with pleasure cars of light weight and fitted with pneumatic tyres as the conditions which prevail on a commercial lorry are so very different. It is true that the risk of skidding in the streets of cities is very much reduced owing to the reduction in the number of horses and the absence of macadam roads, both of which tended to cover the more slippery road surfaces with a layer of slime which acted as a lubricant through which no form of tyre composed entirely Of rubber could penetrate. The most treacherous condition to-day is when a slight shower has just begun to wet a road covered with asphalt or tar paving. On such a surface as this the use of any kind of brake is dangerous, but, with solid tyres and a heavy -vehicle, the risk with frontwheel brakes would be tpo great. A skid with the rear wheels is bad enough, but with care it can be rectified, as the rear of a vehicle is naturally inclined to follow the track of the front wheels if they are kept in a straight line. This is not the case.

however, when front wheels once start to skid, as the advahcing weight of the vehicle tends to increase the error of the front wheels. For this reason it is essential that only one brake should act on the front and rear wheels simultaneously, whilst the other should be applied to the rear wheels only and kept for treacherous road conditions.

Poising the Weight Equally Over the Rear Axle.

The question of how much a body of a lorry should 'Overhang the rear axle is one which does not seem to have been finally settled. As with most motor problems, the designer finds himself faced with difficulties on both sides. There is little doubt that the easiest lorry to handle is one in which the load on the body is evenly poised on the rear axle. With a body of great size, however, this means a very great overhang at the rear. In turning corners with such a body great care has to be taken to prevent the rear portion coming into contact with such things as lamp-posts, walls, etc. With bodies of this class there is more load on the rear springs and axles, whilst jolts due to crossing pot-holes and trenches in the road are exaggerated. It is true that with such a body a skid may be more dangerous owing to the amount of overhang at the rear, but, on the other hand, with a body so poised many drivers find that a skid is more easy to avoid owing to the extreme ease with which such a lorry can be handled.

Three-point Suspension for the Power Unit.

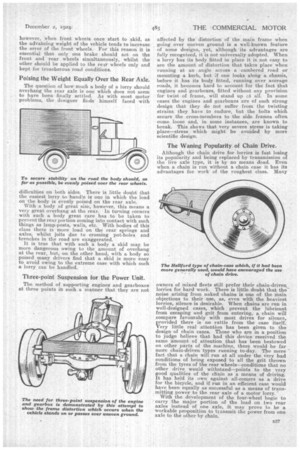

The method of supporting engines and gearboxes at three points in such a manner that they are not affected by the distortion of the main frame when going over uneven ground is a well-known feature of some designs, yet, although its advantages are fully recognised, it is not universally adopted. When. a lorry has its body fitted in place it is not easy to see the amount of distortion that takes place when running at an angle across a cambered road or mounting a kerb, but ;f one looks along a chassis, before it has its body fitted, running over average roads, it becomes hard to account for the fact that engines and gearboxes, fitted without any provision for twist of frame, will stand up at all. In some cases the engines and gearboxes are of such strong design that they do not suffer from the twisting strains they have to endure, but the bolts which secure the cross-members to the side frames often come loose and, in some instances, are known to break. This shows that very severe stress is taking place—stress which might be avoided by more scientific design,

The Waning Popularity.of Chain Drive.

Although the chain drive for lorries is fast losing its popularity and being ieplaced by transmission of the live axle type, it is by no means dead. Even when a chain is run without a chain case it has its advantages for work of the roughest class. Many owners of mixed fleets still prefer their chain-driven lorries for hard work. There is little doubt that the noise arising from naked chains is one of the main objections to their use, as, even with the heaviest lorries, silence is desirable. When chains are run in well-designed cases, which prevent the lubricant from escaping and grit from entering, a chain will _compare favourably with most drives for silence, provided there is no rattle from the case itself. Very little real attention has been given to the design of chain cases. Those who are in a position to judge believe that had this device received the same amount of attention that has been bestowed on other parts of the machine, there would be far more chain-driven types running to-day. The mere fact that a chain will run at all under the Very bad conditions of being exposed to all the grit thrown from the tyres of the rear wheels—conditions that no other drive would withstand—points to the very good qualities of the chain as a means of driving. It has held its own against all-comers as a drive for the bicycle, and if run in an efficient case would have been equally as successful as a means of transmitting power to the rear axle of a motor lorry. With the development of the four-wheel bogie to carry the major portion of the load on two rear axles instead of one axle, it may prove to be a workable proposition to transmit the power from one axle to the other by chain.