Mercedes-Benz 0.30: :oath

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

When the Ministry of Transport discontinued its p.s.v. minimum ground clearance requirement on June 19, it opened the door to Continental manufacturers.

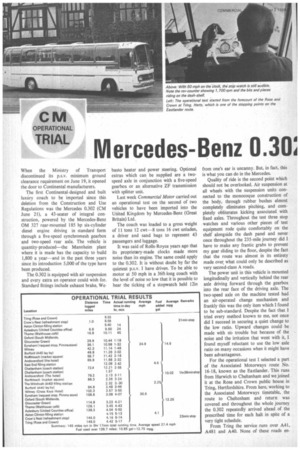

The first Continental-designed and built luxiiry coach to be imported since this deletion from the Construction and Use Regulations was the Mercedes 0.302 (CM June 21), a 43-seater of integral construction, powered by the Mercedes-Benz OM 327 rear-mounted 185 hp six-cylinder diesel engine driving in standard form through a five-speed synchromesh gearbox and two-speed rear axle. The vehicle is quantity-produced-the Mannheim plant where it is made has the capacity to build 1,800 a year-and in the past three years since its introduction 5,000 of the type have been produced.

The 0.302 is equipped with air suspension and every extra an operator could wish for. Standard fittings include exhaust brake, We basto heater and power steering. Optional extras which can be supplied are a twospeed axle in conjunction with a five-speed gearbox or an alternative ZF transmission with splitter unit.

Last week Commercial Motor carried out an operational test on the second of two vehicles to have been imported into the Uriited Kingdom by Mercedes-Benz (Great Britain) Ltd.

The coach was loaded to a gross weight of 11 tons 12 cwt-8 tons 16 cwt unladen, a driver and sand bags to represent 43 passengers and luggage.

It was said of Rolls-Royce years ago that its proprietary-made clocks made more noise than its engine. The same could apply to the 0.302. It is without doubt by far the quietest p.s.v. I have driven. To be able to motor at 50 mph in a 36ft-long coach with the level of noise so low that it is possible to hear the ticking of a stopwatch held 12in from one's ear is uncanny. But, in fact, this is what you can do in the Mercedes.

Quality of ride is the second point which should not be overlooked. Air suspension at all wheels with the suspension units connected to the monocoque construction of the body, through rubber bushes almost completely eliminates pitching, and completely obliterates kicking associated with fixed axles. Throughout the test three stop watches and various other pieces of test equipment rode quite comfortably on the shelf alongside the dash panel and never once throughout the 235-mile journey did I have to make any frantic grabs to prevent my gear sliding to the floor, despite the fact that the route was almost in its entirety made over, what could only be described as very second-class A roads.

The power unit in this vehicle is mounted longitudinally and vertically behind the rear axle driving forward through the gearbox into the rear face of the driving axle. The two-speed axle on the machine tested had an air operated change mechanism and frankly this was the only item which I found to be sub-standard. Despite the fact that I tried every method known to me, not once did I succeed in securing a quiet change to the low ratio. Upward changes could be made with no trouble but because of the noise and the irritation that went with it, I found myself reluctant to use the low axle ratio on many occasions when it might have been advantageous.

For the operational test I selected a part of the Associated Motorways route No. 16-18, known as the Eastlander. This runs from Harwich to Cheltenham and we joined it at the Rose and Crown public house in Tring, Hertfordshire. From here, working to the Associated Motorways timetable, the route to Cheltenham and return was covered and throughout the whole journey the 0.302 repeatedly arrived ahead of the prescribed time for each halt in spite of a very tight schedule.

From Tring the service runs over A41, A481 and A40. None of these roads en deared themselves to me: long stretches of A41 were being excavated for drainage and A481, although it appeared to be intact, is little more than an English country lane. And A40 is undergoing major reconstruction over many miles and in any case is one of the worst main trunk roads in the UK.

Nevertheless extremely light clutch and brake pedals, power steering and a pleasant main gearbox made the drive one to remember. Having covered other service routes in passenger vehicles I was fully aware at the start of this journey that there would be no time to hang about. The route planners have the timetable worked out to a fine art so that a driver must crack on fairly well under normal circumstances. Should he be delayed in a traffic jam or by an accident, then he must pull out all the stops to make up the necessary odd few minutes or more.

The performance of the Mercedes was such that I found it easy to keep to the timetable. The journey was divided by 11 stopping points in each direction with the greatest distance between any two just over 13 miles. It was possible to pick up time on most sections without any real effort. I felt that this was in a greater part due to the handling of the vehicle rather than the fact that we were travelling exceptionally fast. Average speeds well in excess of 30 mph could be achieved while seldom exceeding 50 mph over poor road conditions. The actual timed journey from Tring via Cheltenham and return to Tring absorbed a total period of 5.23 hours and the milometer, which had proved to be completely accurate when checked on M4, turned over 145 miles, to produce an overall average speed of 27.4 mph.

Fuel consumption checks were made over four stretches or the journey and these were extremely revealing. On a section between Aston Clinton and East End just outside Cheltenham, a total distance of 66.9 miles, the Mercedes returned 14.5 mpg. The average speed over this section was 26.8 mph. This fuel consumption was the best

returned during the day, and in fact at no time did the figures fall below 12.25 mpg. The overall average throughout the trip was 12.75 mpg—a creditable performance for a vehicle scaling nearly 12 tons.

Getting to and from the planned test circuit entailed travelling over about 90 miles of roads which I selected as typical of touring services. Many of these were little more than by-ways, with the occasional embankments which can be so detrimental to low and fancy sidepanelling, such as that making up the skirting of a coach body. But so accurate is the handling of the Mercedes that one has no qualms about tackling narrow lanes or the smallest negotiable gaps in traffic.

Although I did not carry out a specially prepared hill climb, a timed ascent of a good stretch of road 0.45 miles long with a gradient of I in 8 was covered in 1min 13.5sec. The lowest gear engaged was second with high axle and the lowest speed recorded was 17 mph.

The test vehicle's power unit, the MercedesBenz OM 327, has a maximum net bhp of 175 and a net torque of 360 lb. /ft. at 1,500 rpm. I found it possible to drive the machine down to an engine speed of around 1,100 rpm and still accelerate quite comfortably back to the higher road speeds. Although the rev, counter showed that the engine would go up to 3200 rpm if required, in practice I than 2,700. seldom saw the reading higher At no time was any exhaust smoke visible and from outside the vehicle the exhaust noise level was commendably low.

One of the points I liked about the controls was that the exhaust brake was linked through a two-way tap to the air-pressure system; with this set in one position the exhaust brake was controlled by the footbrake and when set in the alternative position it came under the control of a heelbutton positioned to be operated by the driver's left foot. As with most exhaust brakes this one, while extremely effective when the machine was in the lower gears, had little effect for general road use.

An air-over-hydraulic braking system is fitted and I was particularly impressed with the delicate control which it was possible to obtain through the brake pedal. On the test vehicle the handbrake was of a powerful multi-pull type but it does not meet the British requirements for secondary braking as the efficiency is not attained on the first pull. It is due to be changed for a single-pull air-assisted unit which will comply. Although I found application of the handbrake extremely noisy I must confess it was about the most powerful I have ever used on a passenger vehicle. A full Commercial Motor road test of this vehicle will be published shortly.