GOOD and Bad in the .S. FORD

Page 53

Page 52

Page 54

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By John F. Moon,

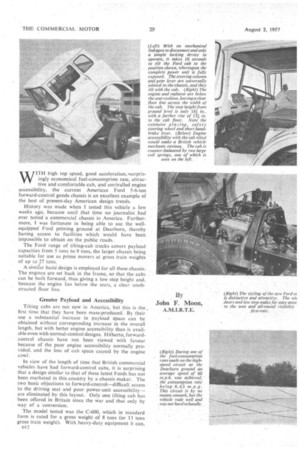

WITH high top speed, good acceleration,4surprisingly economical fuel-consumption rate, attractive and comfortable cab, and unrivalled engine accessibility, the current American Ford 5-6-ton forward-control goods chassis is an excellent example of the best of present-day American design trends.

History was made when I tested this vehicle a few weeks ago, because until that time no journalist had ever tested a commercial chassis in America. Furthermore, I was fortunate in being able to use the wellequipped Ford prbving ground at Dearborn, thereby • having access to facilities which would have been impossible to obtain on the public roads.

The Ford range of tilting-cab trucks covers payload capacities from 5 tons to 9 tons, the larger chassis being • suitable for use as prime movers at gross train weights of up to 27 tons.

A sirnirar basic design is employed for all these chassis. The engines are set back in the frame, so that the cabs can be built forward, thus giving a low step height and, because the engine lies below the seats, a clear unobstructed floor line.

Greater Payload and Accessibility

Tilting cabs are not new in America, but this is the first time that they have been mass-produced. By their use a substantial increase in payload space can be obtained without corresponding increase in the overall length, but with better engine accessibility than is available even with normal-control designs. Hitherto, forwardcontrol chassis have not been viewed with favour because of the poor engine accessibility normally provided, and the loss of cab space caused by the engine cowl.

In view of the length of time that British commercial vehicles have had forward-control cabs, it is surprising that a design similar to that of these latest Fords has not been marketed in this country by a chassis maker. The two basic objections to forward-control—difficult access to the driving seat and poor power-unit accessibility— are eliminated by this layout. Only one tilting cab has been offered in Britain since the war and that only by way of a conversion.

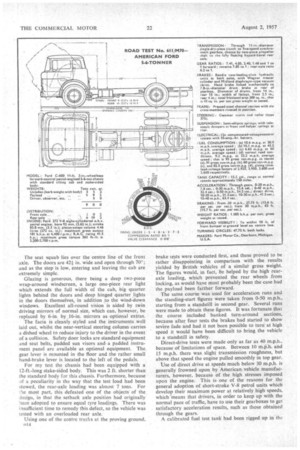

The model tested was the C-600, which in standard form is rated for a gross weight of 8 tons (or 13 tons gross train weight). With heavy-duty equipment it can, ol2 however, be operated at just over 9 tons, or 141 tons as an articulated unit. Only V-8 petrol engines are offered in this range.

The standard engine in the C-600 chassis is the 4.46-litre unit, which is rated to develop 181 gross b.h.p. at 4,400 r.p.m. An optional engine develops 178 b.h.p. at 3,800 r.p.m., but it is a heavy-duty unit with a four-barrel carbufetter, rotor-type oil pump and several other features to give long life at sustained high speed. The standard engine, as fitted in the test vehicle, has a normal double-venturi carburetter.

Several gearboxes are listed, the standard being a four-speed unit. Two five-speed boxes, one with overdrive, are offered, and a further alternative is the new Transmatic sixspeed automatic gearbox, which incorporates a torque converter. A five-speed direct-drive top gearbox was fitted to the vehicle tested.

Because of its gross-weight rating the chassis had heavy-duty non-standard rear springs and axle which allowed a rear-axle loading of 6.7 tons-4 ton more than standard. Similarly, non-standard tyres were fitted at the rear.

Poor Stopping Distances

Surprisingly small brakes, having hydraulic actuation with a diaphragm-type vacuum servo, are employed on the C-600 chassis. As tested, the brakes gave a frictional area of 43 sq. tn. per ton gross weight, which in my opinion is low for a vehicle with a maximum speed of 65 m.p.h. The small braking area is reflected by the relatively poor stopping distances recorded and by the noticeable tendency to fade at high speed.

The chassis-frame is of -1,--in.-thick pressed-steel channels, and the side members have a maximum depth of 91 in., the flanges being 3 in. wide. Riveting is employed throughout. The chassis layout is conventional and the top of the frame is level rearwards from the back of the cab. The radiator is mounted immediately ahead of the engine and at least half of it projects above the top of the frame.

All-steel welded constructed is employed for the cab, the front of which is pivoted directly to the chassis frame. A simple double catch locks it at the rear on to an upright triangulated bridging frame.

The seat squab lies over the centre line of the front axle. The doors are 421 in. wide and open through 705; and as the step is low, entering and leaving the cab are extremely simple.

Glazing is generous, there being a deep two-piece wrap-around windscreen, a large one-piece rear light which extends the full width of the cab, big quarter lights behind the doors and deep hinged quarter lights in the doors themselves, in addition to the wind-,down windows. Excellent all-round vision is aided by twin driving mirrors of normal size, which can, however, be replaced by 6-in. by .16-in, mirrors as optional extras.

The facia is cleanly styled and the instruments well laid out, whilst the near-vertical steering column carries a dished wheel to reduce injury to the driver in the event of a collision. Safety door locks are standard equipment and seat belts, padded sun visors and a padded instrument panel are available as optional equipment. The gear lever is mounted in the floor and the rather small hand-brake lever is located to the left of the pedals.

For my test the chassis had been equipped with a 12-ft.-long stake-sided body. This was 2 ft. shorter than the standard body for this chassis. Furthermore, because at' a peculiarity in the way that the test load had been stowed, the rear-axle loading was almost 7 tons. For the most part, this defeated one of the objects of the design, in that the setback axle position had originally been adopted to ensure equal tyre loadings. There was insufficient time to remedy this defect, so the vehicle was tested with an overloaded rear axle.

Using one of the centre tracks at the proving ground. n14

brake tests were conducted first, and these proved to be rather • disappointing in comparison with the results yielded by British vehicles of -a similar gross weight. The figures would, in fact, be helped by the high rearaxle loading, which prevented the rear wheels from locking, as would have most probably been the case had the payload been farther forward.

The same course was used for acceleration runs and the standing-start figures were taken from 0-50 m.p.h., starting from a standstill in second gear. Several runs were made to obtain these figures. It was fortunate that the course included banked turn-around sections, because after four tests the brakes had started to show severe fade and had it not been possible to turn athigh speed it would have been difficult to bring, the vehicle to a standstill in safety.

Direct-drive tests were made only as far as 40 m.p.h., because of limitations of space. Between 10 m.p.h. and 15 m.p.h. there was slight transmission roughness, but above that speed the engine pulled smoothly in top gear.

Use of direct drive at speeds much below 30 m.p.h. is generally frowned upon by American vehicle manufacturers, however, because of the high stresses imposed upon the engine. This is one of the reasons for the general adoption of short-stroke V-8 petrol units which develop their maximum power at relatively high speeds, whicVmeans that drivers, in order to keep up with the normal pace of traffic, have to use their gearboxes to get satisfactory acceleration results, such as those obtained through the gears.

A calibrated fuel test tank had been rigged up in the cab, and using this, four fuel-consumption runs were conducted around the outer high-speed circuit of the course. The first three were made at fairly constant speeds and on, the third, which was conducted at continuous full throttle, 60 m.p.h. was averaged. The fuel-consumption rate was fairly high, but the two slow tests produced reasonable figures.

I then made a fourth run, during which I tried to simulate English traffic conditions, a difficult task on a one-way, partly deserted test track. To do this I made several stops and changes down, and the 2.58-mile circuit was covered at an average speed of 32.2 m.p.h. The fuel return was 9.2 m.p.g., which again is reasonable, taking into consideration the high power output of the engine and the greedy characteristics of the carburetter when

• accelerating at full throttle.

Maximum of 65 m.p.h.

A fifth-wheel-operated speedometer was used for all these tests and for a maximum-speed run, during which 65 m.p.h. was recorded. This is sufficient for normal American conditions, the legal maximum speed, in Michigan, for example, being 45 m.p.h. The highest truck speed allowed anywhere in the United States is in Wisconsin, where 60 m.p.h. is permitted during daytime and 50 m.p.h. at night.

There being no long gradients either at the proving ground or in the immediate vicinity of Dearborn, I was unable to conduct sustained hill-climb and brake-fade tests, but this was not of great consequence, as the cooling arrangements were clearly adequate and the brakes had already been shown to fade. Climbing power, however, was demonstrated on two of the test hills at the proving ground, the steepest of which is 1 in 3.3, whilst the other is 1 in 5.8.

A steady bottom-gear climb, with the engine turning at 3,000 r.p.m., was made up the steeper slope, but when the truck was stopped on this gradient, clutch slip made a re-start impossible and I was only just able to hold the vehicle on that gradient with both the hand and foot brakes fully applied.

On the less steep gradient a non-stop climb was made in second gear and a smooth re-start was accomplished with bottom gear engaged. The performance of the Ford on these two slopes was generally convincing and amply demonstrated the power available, particularly as the axle ratio was the highest of the three offered. The lowest is 7.2 to 1, with a further option of two-speed axles ranging from 6.33 and 8.81 to 1.

Unfortunately, there was insufficient time to conduct maintenance tasks on the vehicle, but I was able to raise the cab and see for myself how well exposed the engine is for attention. It took only 10 seconds to lift the cab

and this did not entail any hard work, as there are two large coil springs close to the pivots which serve to counterbalance the weight of the cab.

With the cab lifted there is hardly any part of the engine which cannot be reached with ease, and anyone working on the engine can stand close up to it on each side.

Although the complete unit is beneath the seat, it is unnecessary to tilt the cab to gain access to the oil and water fillers or the dipstick, as the squab on the passenger side can be tipped forward, thereby revealing a detachable panel which gives access to these items. Furthermore, the distributor, which is at the rear of the engine and is normally most difficult to reach, can be attended to without even raising the cab, as it lies beneath the cab-support bridge and can be reached from behind the cab.

It takes only nine seconds to tower the cab and lock it in position. The speed with which the power unit can be reached should be sufficient indication to British manufacturers of the superlative advantages of this design, and although the original cost would be slightly greater than that of a fixed cab, its additional cost can be quickly recovered by reduced delays in the workshops.

Additionally, it may be found that fitters will be more thorough when working on the engine, because they can get at it more easily. Operators of this type of vehicle in the United States have estimated that tilting cabs can halve maintenance charges.

Pleasant to Drive

The Ford is a pleasant enough vehicle to drive and the ride compares favourably with that obtained with current British medium-weight designs. The full-width cab is roomy, there being ample space for three passengers alongside the driver and the seating is comfortable.

A fair amount of engine noise penetrates the cab. despite thick layers of insulation material, but there is no engine vibration or heat transference. All the controls are well placed and, with the exception of the rather short hand-brake lever, are easy to reach. But the gear-change mechanism is sloppy and there is long travel between thirdand fourth positions, which can make that change a trifle vague.

The C-600 lorry sells in America for approximately 11,125. This figure, although high by British standards, is not over-expensive for an American vehicle, bearing in mind the difference in the cost of living between the two countries. The main lesson to be learned in Great Britain from this Ford design is the cab: mechanically the chassis is no better than British models, taking into account the conditions governing its design.