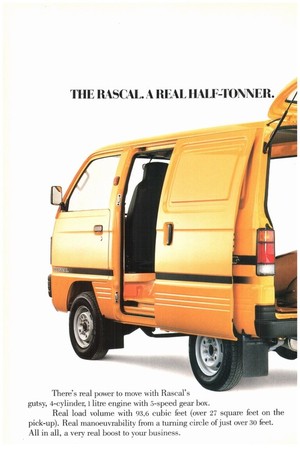

THE RASCAL A REAL HALF-TONNER.

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

There's real power to move with Rascal's gutsy, 4-cylinder, I litre engine with 5-speed gear box.

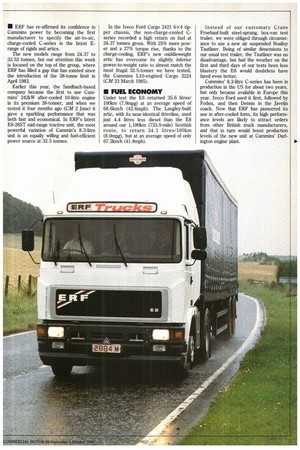

Real load volume with 93,6 cubic feet (over 27 square feet on the pick-up). Real manoeuvrability from a turning circle of just over 30 feet. All in all, a very real boost to your business. • ERF has re-affirmed its confidence in Cummins power by becoming the first manufacturer to specify the air-to-air, charge-cooled C-series in the latest Erange of rigids and artics.

The new models range from 24.37 to 32.52 tonnes, but our attention this week is focused on the top of the group, where ERF has filled a gap that has existed since the introduction of the 38-tonne limit in April 1983.

Earlier this year, the Sandbach-based company became the first to use Cummins' 242kW after-cooled 10-litre engine in its premium 38-tonner, and when we tested it four months ago (CM 2 June) it gave a sparkling performance that was both fast and economical. In ERF's latest E8-26ST mid-range tractive unit, the most powerful variation of Curnmin's 8.3-litre unit is an equally willing and fuel-efficient power source at 32.5 tonnes. In the Iveco Ford Cargo 2421 6x4 tipper chassis, the non-charge-cooled Cseries recorded a high return on fuel at 24.37 tonnes gross. With 25% more power and a 27% torque rise, thanks to the charge-cooling, ERF's new middleweight artic has overcome its slightly inferior power-to-weight ratio to almost match the most frugal 32.5-tonner we have tested, the Cummins L10-engined Cargo 3224 (CM 23 March 1985).

• FUEL ECONOMY

Under test the E8 returned 35.6 litres/ 100km (7.9mpg) at an average speed of 68.6km/h (42.6mph). The Langley-built artic, with its near-identical driveline, used just 4.4 litres less diesel than the E8 around our 14801cm (733.9-mile) Scottish route, to return 34.1 litres/100km (8.0mpg), but at an average speed of only 67.21trn/h (41.8mph). Instead of our customary Crane Fruehauf-built steel-sprung, box-van test trailer, we were obliged through circumstance to use a new air suspended Boatloy Tautliner. Being of similar dimensions to our usual test trailer, the Tautliner was no disadvantage, but had the weather on the first and third days of our tests been less blustery the E8 would doubtless have fared even better.

Cummins' 8.3-litre C-series has been in production in the US for about two years, but only became available in Europe this year. Iveco Ford used it first, followed by Foden, and then Dennis in the Javelin coach. Now that ERF has pioneered its use in after-cooled form, its high performance levels are likely to attract orders from other British truck manufacturers, and that in turn would boost production levels of the new unit at Cummins' Darlington engine plant.

• DRIVEUNE

ERF's experience in installing the LTAA10-325 in the El0 chassis has clearly been put to good use in the E8. The compact inter-cooler system uses castaluminum ducting with silicon-rubber hoses and stainless-steel hose clips.

The intercooler matrix is mounted rather neatly ahead of the coolant radiator, but instead of the inlet and outlet pipes being routed from the top, as they are in the E10-325, they are fed from a mid-height position around the sides.

This reduces the overall height of the unit, avoiding any changes to cab floor. Installed in its charge-cooled form, the 6CTAA8.3-265 produces its 183kW (245hp) peak power at 2,400rpm with maximum torque of 954Nm (704Ibft) at 1,450rpm, to EEC ratings.

The C-series is 300kg lighter than the turbocharged L10 and is more compact, but the smaller 8.3-litre unit has to spin 300rpm faster to match the L10's power output. It also produces 6.2% less torque, 50rpm higher up the rev band.

The Cargo's L10 uses a single 406mna Valeo clutch disc: at 32.5 tonnes ERF specifies a pair of 355mm Dana Spicer ceramic-faced plates. The clutch is not air assisted, but neither is it particularly heavy in operation.

The E8 also uses Eaton's latest gearbox, the all-synchromesh 6109 ninespeeder (with crawler). Of the two versions available from Eaton, ERF has chosen the direct-top-gear unit as standard, rather than the 0.75:1 overdrive version, matching it to a 4.30:1 final drive Rockwell S160E drive axle.

The main chassis rails are the same as those used in the El0 but the frame is waisted inwards from 940 to 820mm from just behind the front springs. This gives room to fit 11R 22.5 tyres all round and also results in shorter cross-members which combines with other weight savings in the clriveline, cab and chassis equip ment to keep the E8-26ST's kerbweight down to an impressive 5,465kg in bare running trim.

• PERFORMANCE

With this choice of driveline and equipment the E8 has a design top speed of 1071un/h (66.5mph). Moving off from rest on the flat calls for a starting sequence of third, skips to fifth and seventh, followed by eighth and ninth. A second to fourth start will suffice for most gradients.

The E8's design restart figure is easily attainable in dry conditions, as it proved on the 25% (1-in-4) test hill at MIRA, which it sailed up at the first attempt.

Relatively high gearing uses the engine's output characteristics to great effect and proved an astute compromise for the mixed bag of conditions encountered over our Scottish test route.

Despite head and cross winds the E8 produced good results on the motorway section where the C-series engine pulled strongly above 1,900rpm, and had to be held in check at the 60mph (961cm/h) speed limit. This meant holding it on the footbrake, which was effective during determined braking but rather insensitive for gradual application. Our test vehicle, one of a batch of 50 pre-production models undergoing service trials, did not have an exhaust brake fitted, but ERF says that production models will have one fitted as standard. The C-series is a more lightlybuilt engine than its larger sisters, so there will not be the usual ERF Jake brake option.

Where the E8 really excelled was between Gretna and Hamilton. With most of this section undertaken at speeds between 64 and 80km/h engine revs hovered between 1,400 and 1,750rpm, which ensured that there was over 900Nm (675Ibft) of torque on tap. This not only enabled it to maintain good progress up long drags, like the run up to Beattock Summit, with no more than two down changes, but the engine's specific fuel consumption remained well below 205W kW. hr.

The combination of high torque and well-spaced gear ratios allows fairly crisp acceleration, even when laden to the full 32.5-tonne capacity.

On the test track the E8's times from rest to 481cm/h and from 64 to 80krn/h were several seconds less than its nearest rival, the L10-250 engined 3224. Over the timed hillclimbs the E8 cruised easily up Carter Bar in fifth gear. It took our toughest test hill, Blackhill, near Consett, in six minutes, 27 seconds — 45 seconds quicker than the Cargo — but the extra torque from the Cargo's slower-revving 10-litre engine ensured that the positions were reversed over the longer M18 and M1 motorway drags.

• HANDLING

A detailed comparison with the ElO's specification reveals many similarities. The two models use the same ZF 8096 power steering which, with an identical 3.2m wheelbase and at 32.5 tonnes gross, is effortless across the E8's average 12.8m turning circle, even at low revs. The E8's two-leaf suspension, with a single leaf helper spring and anti-roll bar at the rear, is also E10-derived and gives, in general, a good ride over smooth surfaces. On the poorer road surfaces of the North-East, however, it gave a rather choppy ride, in spite of a properly distributed and secured load of 50kg sandbags.

• CAB COMFORT

Our test vehicle's accelerator pedal was set at a sharp angle and jarred occasionally when the bouncy ride transmitted itself through the driver's foot, making it difficult to control on downhill runs.

This was exacerbated by an unusually uncomfortable Isringhausen air-sprung seat. Its economy-size base and backrest were flat and unsupporting, and on cornering it felt about as retentive as a park bench. The seat's one redeeming feature was that the air springing could be locked out over bumpy roads.

Despite the engine's high revs and its healthy sound when lugging up grades, noise levels inside the cab are among the lowest in its class, with only 72dB(A) registering at 2,050rpm in top gear.

ERF has carried out a number of changes to the already revised SP4A cab for the E8 models, and these are mainly for the benefit of the driver.

The doors, for example, open just beyond 90° to improve access. On our test vehicle the check-straps refused to hold the doors back, but the extra width is noticeable. Modified door hinges protrude slightly, but a new front panel with flared edges and chamfered corner deflectors hides them neatly.

Steps and spotlight recesses are incorporated into the lower front panel: the upper panel will allow access for daily service checks. The modified cab still offers 60° of tilt, as long as the driver remembers to raise the front panel. This releases a pressure valve which controls the hydraulic circuit for the tilt mechanism.

Climbing into the cab is much easier thanks to the addition of a third step. The top two (200inm apart) form part of the cab side, while the bottom one (490min high when laden) is attached to the air dam. The top pair seem close together, but they provide an easy path into the cab for all heights of driver.

Once inside the well-finished cab, the most noticeable change is the extra space over the engine, gained through the removal of the front storage box. This makes cross-cab movement much easier and gives a more spacious feel.

An untidy mix of extra switches, including the diff-lock button, is set into a small panel below the curved end of an uninspiring fascia. The fuel and battery-condition gauges are partially obscured by the steering wheel, while the rev counter, to which the driver's attention is usually drawn, lacks any sort of colour coding.

Gear changing in the Eaton 6109 is smooth enough, aided by the longish throw of the gear lever, but the rangechange button is stiff and needs to be more prominent.

Forward visibility is good with a trio of wiper blades to keep the screen clear. The door windows have an obstructive vertical strip in them, but the cab's outer corner deflectors effectively keep them free of spray. We approve of the useful heated rearview mirrors, but while halfsize windows behind the B-posts may save on unladen weight they are no help when manoeuvring through busy city cen tres such as Edinburgh. The heater fan does not feel too powerful, even on boost, and the supply of cold air at face level is none too impressive either.

Storage space is not lacking, however, with large compartments behind the header rail, pockets in each door and large storage areas under the raised bunk. There is also a fair-sized pocket in front of the passenger seat.

• SUMMARY

ERF's new E8 tractive unit has all the necessary qualifications to compete for top honours in the 29-32.5-tonne sector. In the year to date, the company's market share has risen to 14.5% from last year's 9.3%, and the performance of the new model will not have harmed its chances of continuing that growth. A low (5.46tonne) kerbweight provides excellent earning potential and its nifty, thrifty performance will put the E8 high in the productivity league.

One or two areas of the cab let it down, but no doubt the marketing moguls of Sandbach are well aware of them. As for the business end of the truck, the E8-26ST more than meets the customers' needs, and its £33,910 retail price is competitive too.

Ll Bryan Jarvis