Road Test of AEC t/Willowbrook Service Bus

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 65

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

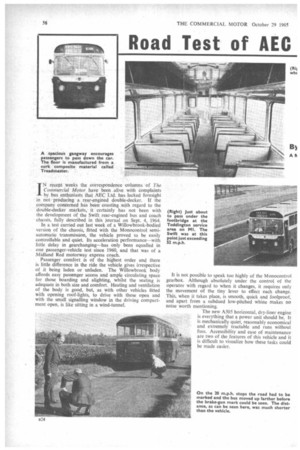

IN recent weeks the correspondence columns of The Commercial Motor have been alive with complaints by bus enthusiasts that AEC Ltd. has lacked foresight in not producing a rear-engined double-decker. If the company concerned has been coasting with regard to the double-decker markets, it certainly has not been with the development of the Swift rear-engined bus and coach chassis, fully described in this journal on Sept. 4, 1964. In a test carried out last week of a Willowbrook-bodied version of the chassis, fitted with the Monocontrol semiautomatic transmission, the vehicle proved to be easily controllable and quiet. Its acceleration performance—with little delay in gearchanging—has only been equalled in one passenger-vehicle test since 1960, and that was of a Midland Red motorway express coach.

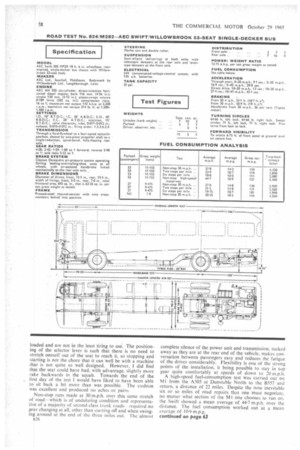

Passenger comfort is of the highest order and there is little difference in the ride the vehicle gives irrespective of it being laden or unladen. The Willowbrook body affords easy passenger access and ample circulating space for those boarding and alighting, whilst the seating is adequate in both size and comfort. Heating and ventilation of the body is good, but, as with other vehicles fitted with opening roof-lights, to drive with these open and with the small signalling window in the driving compartment open, is like sitting in a wind-tunnel. It is not possible to speak too highly of the Monocontrol gearbox. Although absolutely under the control of the operator with regard to when it changes, it requires only the movement of the tiny lever to effect each change. This, when it takes place, is smooth, quick and foolproof, and apart from a subdued low-pitched whine makes no noise worth mentioning.

The new A505 horizontal, dry-liner engine is everything that a power unit should be. It is mechanically quiet, reasonably economical and extremely tractable and runs without fuss. Accessibility and ease of maintenance are two of the features of this vehicle and it is difficult to visualize how these tasks could be made easier. Originally there were two distinctly different chassis models available, both known as the Swift 505. but economics have demanded. that the straight-framed version—which was to have filled the role of luxury coach chassis—be discontinued in favour of the dropped-frame model, which can, of course, fulfil both duties. The test vehicle was of the dropped-frame type, now the only one

available. This must, of course, present -oblems to the bodybuilder, but from what I have seen of e test vehicle they do not seem to be insurmountable. Suspension of the test vehicle was of conventional design ith semi-elliptic leaf-springs at front and rear axles. The ar springs are 3-5 in. wide and 62 in. long and telescopic tamers are fitted. The front springs are shorter and ider, being 4 in. by 50 in. long. To avoid protrusion iove the top run of the frame-members, lever-type impers are used on the front axle. In both cases the 1ring hangers are fitted alongside the main frameembers. The front spring units are bolted fore-and-aft to outriggers and the rear spring units direct to the le-web of the frame.

Air-suspension is offered as an option, this being the ell-tried AEC passenger-chassis type used for a number years. The rear axle in this design is located by parallel. ailing radius-rods and the front axle by a leaf-spring. ere being insufficient clearance between the ground and or levels to allow double radius rods. The rnain Inction of the leaf spring in this case is to provide axle cation.

An area around Barton-in-the-Clay, Bedfordshire. was iosen for the test, and collecting the vehicle from the EC engineers at Toddington I first had to negotiate about re miles of extremely narrow and twisting roads. Here was immediately noticeable that the steering and general rattling of the machine was impeccable. Vision from the lying position could not be bettered but the strong itumn sunshine quickly showed me that the window-line was extremely high and I found it impossible to dodge the dazzle except by holding up one hand as a shield. The sun-blind fitted to the offside screen could with advantage be wider and deeper, and the addition of an extra blind in the side window would be an asset.

The real worth of the Monocontrol gearbox for bus operation became evident when the acceleration tests were carried out. Times through the gears were the best achieved on a road test of a service-bus carried out by this journal for at least five years. Considering the g.v.w. of 10 tons 18 cwt., which puts the machine among the heaviest single-deckers tested, and taking intotaccount the inevitable power loss and slip that occurs when using this type of transmission, this was no mean achievement.

When such a vehicle as this is operating in its natural environment, it is almost certain that smart acceleration— or the lack of it—will be a point that will make it loved or hated by its handlers. A vehicle that is not readily accepted by the drivers is seldom a good proposition in these days of labour shortage. No such problems should arise with the Swift. Acceleration figures were achieved by holding the throttle-pedal hard down on the stop and selecting the next higher gear a fraction of a second before the engine reached peak revolutions. This took into account a slight delay that is built into the electro-pneumatic gearchange—to avoid the possibility of a too-jerky change being made—and ensured that there was no interference from the engine governor to affect the figures.

Direct-drive acceleration was again very good. With absolute smoothness the vehicle pulled away from 10 m.p.h. in top gear and reached 20 m.p.h. in 13 sec., 30 m.p.h. in 2745 sec. and 40m.p.h. in 43-1 sec. Full information about the acceleration tests can be seen in the panel.

When conducting the fuel-consumption tests on A6, Barton-in-the-Clay to Clophill, again, the suitability of the Monocontrol system made itself felt in no uncertain terms. Completing the six-stops-per-mile runs—of which there were two carried out over a six-mile circuit—was by far the most easily accomplished test of this kind that I have made. Footbrake and throttle pedals are both nicely

loaded and are not in the least tiring to use. The positioning of the selector lever is such that there is no need to stretch oneself out of the seat to reach it, so stopping and starting is not the chore that it can well be with a machine that is not quite so well designed. However, I did find that the seat could have had, with advantage, slightly more rake backwards in the squab. Towards the end of the first day of the test I would have liked to have been able to sit back a bit more than was possible. The cushion was excellent and produced no aches or pains Non-stop runs made at 30 m.p.h. over this same stretch of road—which is of undulating condition and representative of a majority of second-class I runk roads required no gear changing at all. other than starting off and when swinging around at the end of the three miles out. The almost 1126 complete silence of the power unit and transmission, lucked away as they are at the rear end of the vehicle, makes conversation between passengers easy and reduces the fatigue of the driver considerably. Flexibility is one of the strong points of the installation, it being possible to stay in top gear quite comfortably at speeds of down to .20 m.p.h. A high-speed fuel-consumption test was carried out on Ml from the A505 at Dunstable North to the B557 and return, a distance of 22 miles. Despite the now inevitable six or so miles of road repairs that one must negotiate. no matter what section of the M I one chooses to run on. the Swift showed a mean average of 44-7 m.p.h. over the distance. The fuel consumption worked out at a mean averaue of 10-9 m.p.g,.

continued on page 63 ecause of the possibility of a complete test run being le useless by road works, I decided to do this test in parts. The run north, on which I was able to keep almost top speed for the whole distance, returned an rage speed of 48-9 m.p.h. and a consumption of n.p.g. On the leg south I was continually baulked by vy vehicles negotiating the long stretches of road works, had the added disadvantage of a head wind. On this the average speed was 40.5 m.p.h. and the fuel sumption 9.8 m.p.g. me point that was emphasized on the motorway run the lack of noise from wind passing over the body*. Although the wind could be heard (and on the them n leg there was a 20 m.p.h. headwind) at no time it objectionable. There was, -above 50 m.p.h., some ht kicking in the steering gear, caused, I think, by fact that new tyres had been fitted without the wheels ig balanced. Apart from this, the steering was accurate light with just the right amount of castor action. ual top speed proved to be slightly over 53 m.p.h, taking ) account a five per cent high reading on the edometer.

/loving from MI to Bison Hill, which is 0-75 miles g with an average gradient of 1 in 10 and a steepest dient of I in 6-5, the hill-climb, brake-fade, stop-and-1 and handbrake-holding tests were carried out. As

vehicle cooling system incorporates a header tank, vas impossible to take coolant temperatures. There did , however, appear to be any undue rise in the engine merature at the end of the climb, which was made a total time of 3 min. 4 sec. During this time, first gear ; engaged for 60 sec. and the minimum speed recorded 5 13.5 m.p.h.

ry little fade

furning round and facing down the hill, the vehicle allowed to coast to the bottom at about 20 m.p.h.

h a continuous application of the footbrake. When re was no longer sufficient momentum to keep up this ed, third gear was engaged and the vehicle was driven full throttle against the brakes. A full-pressure stop de at the bottom of the hill from 20 m.p.h. produced Tapley meter reading of 65 per cent, only 11 per cent ier than that produced by the cold brake tests.

Facing both up and down the hill the handbrake held vehicle with complete ease. When letting the vehicle ) down backwards or forwards a quick snatch on the -assisted lever stopped it immediately and held it firmly tii the lever was released. First and reverse gear starts re made easily.

cold brake tests which had been carried out earlier had )ved that the equipment was very good indeed. From m.p.h. the average distance taken to stop the vehicle s 23.125 ft —that is, 18-7 ftisec2 and from 30 m.p.h. it was 95 ft., giving an average retardation of 19 ft/sec2. On

all the full-pressure stops made, there was evidence that the tyres were just on the point of starting to slide, there being slight marking on the road. This proved that the effort applied to the brake shoes was just about right. It might be said that the retardation figures were a bit too good for a vehicle that may well be carrying standing passengers, but I am sure that less severe injury would result than would be the case if a vehicle was unable to stop in time to avoid an accident. The handbrake, which as mentioned earlier is of the air-assisted variety, proved to be well up to the job of emergency braking, producing an average Tapley meter reading of 36 per cent from

20 m.p.h. It is mechanically linked to the rear wheel brakes only, whilst in the linkage adjacent to the rear axle a pull-valve is installed which is piped to the rearmost diaphragm of Clayton Dewandre triple-diaphragm chambers at each wheel. With the service brake air-line connected to the diaphragm closest to the camshaft, the third diaphragm is located between the two thus prevening complete loss of air in the event of a rupture taking place. When checking this unit for efficiency, I found it easy to pull the lever to the end of its ratchet with little effort, In normal service it is as light to operate as most private cars.

I was disappointed to see that the electrical control switches, although nicely laid out, were of three different types. Apart from being a nuisance in service, the use of two units that would have graced a Victorian mansion, for the heater controls, was, I thought, a bit out of character. Neither did I like the old type of running-light switches which I know from experience are constantly falling apart. The positioning of the trafficator warning-light left something to be desired, as it was conveniently masked by the rim of the steering wheel. In the absence of a self-cancelling device I prefer to see a flasher unit that is audible when operating, as well as having a warning light.

The only other complaint I had about the driving position was the intrusion into the foot compartment of a seemingly useless cowling that houses the radiator unit when the body is fitted to the Leyland Leopard. This unnecessarily restricts the available space for the driver's left foot, which must be kept in one (not too comfortable) position indefinitely.

For one-man operation the layout of the Swift is good. and the wide, step-free gangway encourages passengers to "pass down the car" and leave room for others. The air-operated doors, which are in two pieces and swing flush with the sides of the entrance, leave almost the full width of the entrance clear for boarding and alighting passengers.

Screenwipers and mirror equipment are well placed and adequate for the job. The styling of the body in general leaves nothing to be desired, except that I wonder what the cost and availability of the double-curved screens would be should one be unfortunate enough to have one knocked out away from the base.