Satisfying the "Unwilling Seller"

Page 128

Page 129

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

/F the problem of discovering a suitable formula for the value of impressed vehicles be difficult, that in relation to passenger vehicles is at least no more simple. The uses

of passenger vehicles are not so diverse, but the conditions governing depreciation are more varied. Thus, buses on regular urban service come at one end of a long scale with a particularly low rate of depreciation, whilst the coaches employed for excursions and tours are at the other and are subject to a high rate of obsolescence. It is almost impossible to arrive at a mean figure which will be acceptable to all parties concerned.

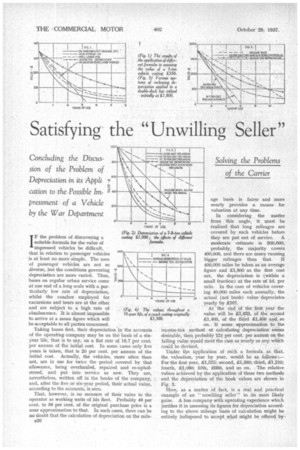

Taking buses first, their depreciation in the accounts of the operating company may be on the basis of a sixyear life, that is to say, on a flat rate of 16.7 per cent. per annum of the initial cost. In some cases only five years is taken, that is 20 per cent. per annum of the initial cost. Actually, the vehicles, more often than not, are in use for twice the period covered by that allowance, being overhauled, repaired and re-upholstered, and put into service as new. They are, nevertheless, written off in the books of the company, and, after the five or six-year period, their actual value, according to the accounts, is zero.

That, however, is no measure of their value to the operator as working units of his fleet. Probably 40 per cent. to 50 per cent_ of the original purchase price is a near approximation to that. in such cases, there can be no doubt that the calculation of depreciation on the mile e26 age basis is fairer and more nearly provides a means for valuation at any time.

In considering the matter from this angle, it must be realized that long mileages are covered by such vehicles before they are put out of service. A moderate estimate is 300,000: probably, the majority covers 400,000, and there are many running bigger mileages than that. 1.f 400,000 miles be taken as an average figure and £1,800 as the first cost net, the depreciation is (within a small fraction) at the rate of id. per mile. In the case of vehicles covering 40,000 miles each annually, the actual (not book) value depreciates yearly by £167. At the end of the first year the value will be £1,633, of the second £1,466, of the third £1,400 and so on. If some approximation to the income-tax method of calculating depreciation seems desirable, then probably 12i per cent, per annum on the falling value vpuid meet the case as nearly as any which Could be devised.

Under the application of suCh a formula as that, the valuation, year by year, would be as follows:— For the first year, £1,575; second, £1,380; third, £1,210; fourth, £1,060; fifth, £930, and so on. The relative values achieved by the application of these two methods and the depreciation of the book values are shown in Fig. 3.

Here, as a matter of fact, is a real and practical example of an "unwilling seller" in its most likely guise. A bus company with operating experience which justifies it in assessing its figures for depreciation according to the above mileage basis of calculation might be entirely indisposed to accept what might be offered by' the Most willing buyer, who, naturally, would base his price on some much higher rate of depreciation.

On the other hand, coaches employed for excursions and tours, private parties and contracts, suffer a high rate of depreciation, especially if they be centred in the more important cities and towns, where competition is keen and where the public is educated up to the point of demanding most up-to-date and luxurious vehicles. Under such conditions a coach costing, say, £1,500 when new, would be unlikely to fetch more than £500 in a couple of years, when, by stress of that competition, it becomes necessary to replace it.

At that period of its life, however, it probably passes into the hands of smaller operators in less exacting areas. There the attraction to passengers is that of low fares, rather than of luxurious equipment and up-to-date vehicles. From that time onwards the rate of depreciation is much slower. Actual figures for value can hardly be derived from any set formula. Probably the following are sufficiently near for the present purpose : —At the end of the first year after re-sale, £300, second £180, third gm, fourth £120, and so on.

A • different factor enters into the transaction in a national emergency, in respect of vehicles of this description, namely, the diminution, possibly even cessation, of the demand for their use. For a time, at least, such operation will be out of the question, if for no other reason than that fuel will not be available. In other words, these owners will become "wining sellers" at almost any price likely to be offered by "willing buyers." In such cases, the income-tax formula will meet the case, at least after the passing of the second year, when the value of the vehicle has dropped to the £500 mark.

The foregoing are the two principal classes of use of passenger vehicles. As is well known, there is an infinite gradation as between one and the other, and there are many points at which the two merge. For example, many of the larger operators, particularly those who are not concerned with the use of double-deck buses, find it convenient to pass their vehicles from one class of use to another to meet the requirements of their services.

When new, they are put on excursions and tours, subsequently going into regular urban service. Then, again, they are moved from route to route, placing the least reputable buses on those routes where custom is almost obligatory on the passengers, and keeping the best vehicles on services where the attraction of a little extra comfort or luxury will induce increased patronage.

I have to admit that there is, perhaps, not much in what I have written in this and the previous article in the way of guidance to the price which an unwilling seller should ask, except that I have, I think. almost shown that a figure based upon the income-tax method of calculation will meet the majority of cases and satisfy this unwilling seller if he is to be satisfied at all.

After all, in the case of a national emergency arising, which will bring about the state of affairs we have in mind, is it likely that there will be a sufficient number of "unwilling sellers" to make that solution of

major importance? S.T.R.