A 6-ti with 143 b.h.p.

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By John F. Moon, A.1101.1.R.T.E.

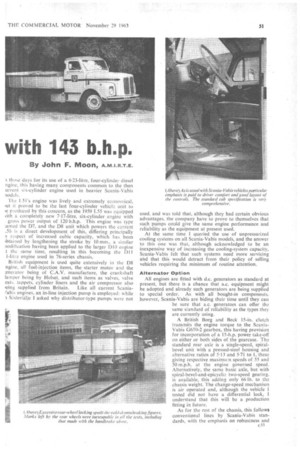

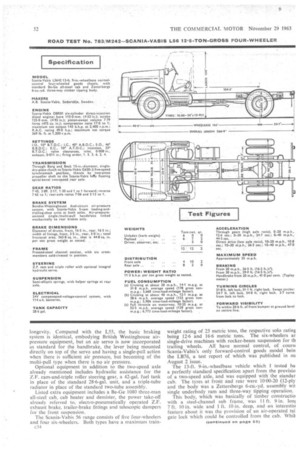

THE idea of purchasing a vehicle with an unladen weight of 6 tons to carry a load of 6 tons • would horrify most British operators. Indeed, the thought horrified me. With these bald facts in mind, therefore, the Swedish Scania-Vabis L56 seems to be a vehicle with no future, but actually this is far from the truth, as numerous other factors have to be taken into consideration, amongst these being a gross train-weight rating of 25 metric tons.

In any case, the unladen-weight figure of 6 tons quoted above is in itself deceptive, because this applied to a fairly short-wheelbase example of an L56 that I tested in Sweden recently and which was equipped with a particularly robust 6-cu.-yd. three-way tipping body: the chassis-cab kerb weight of this particular model is approximately 4 tons 10 cwt., which puts things in a more favourable light!

For many years there has been a steady market in Sweden for 6-ton payload vehicles, this type being comparable in usage to the British 7-tonner. Swedish operating conditions, however, tend . to be considerably more severe than those in Britain, and furthermore, Swedish operators have become conditioned to buying robust, highquality chassis for which they are prepared to pay a fair amount of money. They want their vehicles to last a long time, and appreciate that the only way to guarantee longevity is to buy a really high-class product. , High quality can often lead to high unladen weight, hence our original 6-tonner with a 6-ton kerb weight. Where does all this weight come from, one might ask. Well, to begin with, there's a 7-8-litre diesel engine with a net output of 143 b.h.p., behind which is a fairly hefty fivespeed gearbox with synchromesh on the upper four ratios, and a substantial driving axle which, in the case of the test vehicle, had two-speed gearing. The chassis frame is no willowy assembly either, having 9-9 in. by 3-3-in. by 0-3-in, side members, whilst 3-in.-wide springs and full ai braking—with an assisted handbrake as standard—ar other points of the specification.

So far as performance is concerned, the L56 shows u] quite well when compared with British 12-ton-gros machines. . A fuel-consumption rate of 141 m.p.g. wa returned at an average speed of 31-8 m.p.h. over a difficuli hilly test course, whilst a very fast full-throttle run alon. a stretch of motorway resulted in a rate of 10.25 rn.p.g which is not too bad in view of the 52-5-m.p.h. averig speed. From a standstill, 30 m.p.h. could be reached i. 24.7 see., whilst restarts could be made on a 1-in-5gradient with two ratio-combinations in hand. Brakin performance, however, was a little below par in that th power of the system made rear-wheel locking all too eas3 and the resulting skidding added to the overall stoppin distances.

1963 Design

The L56 is the 1963 successor to the L55, which wa introduced in 1959. The L55 in turn replaced the L5 6-tonner, an example of which I tested in Sweden toward the end of 1954, the report having been published in at' February 25, 1955 issue. The L51 was of technical intere, those days for its use of a 6-23-litre, four-cylinder diesel ngine, this having many components common to the then urrent six-cylinder engine used in heavier Scania-Vabis node]

The L51 's engine was lively and extremely economical, iut it proved to be the last four-cylinder vehicle unit to le produced by this concern, as the 1959 L55 was equipped iiith a completely new 7-17-litre, six-cylinder engine with . gross power output of 120 b.h.p. This engine was type lamed the D7, and the D8 unit which powers the current ..56 is a direct development of this, differing principally a respect of increased cubic capacity, which has been ibtainecl by lengthening the stroke by 10 mm., a similar nodification having been applied to the larger D1O engine .t the same time, resulting in this becoming the D 1 1-litre engine used in 76-series chassis.

British equipment is used quite extensively in the D8 .ngine, all fuel-injection. items, the starter motor and the ;enerator being of C.A.V. manufacture, the crankshaft tamper being by Holset, and such items as valves, valve eats, tappets, cylinder liners and the air compressor also icing supplied from Britain. Like all current Scaniaiabis engines, an in-line injection pump is employed: while Siidertalje I asked why distributor-type pumps were not used, and was told that, although they had certain obvious advantages, the company have to prove to themselves that such pumps could give the same engine performance and reliability as the equipment at present used.

At the same time I queried the use of unpressurized cooling systems on all Scania-Vabis models, and the answer to this one was that, although acknowledged to be an inexpensive way of increasing the cooling-system capacity, Scania-Vabis felt that such systems need more servicing aid that this would detract from their policy of selling vehicles requiring the minimum of routine attention.

Alternator Option

All engines are fitted with d.c. generators as standard at present, but there is a chance that a-c. equipment might be adopted and already such generators are being supplied to special order. As with all bought-in components, however, Scania-Vabis are biding their time until they can be sure that a.c. generators can offer the same standard of reliability as the types they are currently using.

A British Borg and Beck 15-in, clutch transmits the engine torque to the ScaniaVabis 6650-2 gearbox, this having provision for incorporation of a 15-11.p. power take-off on either or both sides of the gearcase. The standard rear axle is a single-speed, spiralbevel unit with a pressed-steel housing and alternative ratios of 5-13 and 5-71 to 1, these giving respective maximum speeds of 55 and 50 m.p.h. at the engine governed speed. Alternatively, the same basic axle, but with spiral-bevel-and-epicyclic two-speed gearing, is available, this adding only 66 lb. to the chassis weight. The change-speed mechanism is air operated and, although the vehicle tested did not have a differential lock, I understand that this will be a production fitting in future.

As for the rest of the chassis, this follows conventional lines by Scania-Vabis standards, with the emphasis on robustness and c33

longevity.Compared with the L55, the basic braking system is identical, embodying British Westinghouse airpressure equipment, but an air servo is now incorporated as standard for the handbrake, the lever being mounted directly on top of the servo and having a single-pull action when there is sufficient air pressure, but becoming of the multi-pull type when there is no air pressure.

Optional equipment in addition to the two-speed axle already mentioned includes hydraulic assistance for the Z.F. cam-and-triple roller steering gear, a 42-gal. fuel tank in place of the standard 28-6-gal. unit, and a triple-tube radiator in place of the standard two-tube assembly.

Listed extra equipment includes a Be-Ge 1080 three-man all-steel cab, cab heater and demister, the power take-off already referred to, electro-pneumatically operated Z.F. exhaust brake, trailer-brake fittings and telescopic dampers for the front suspension.

The Scania-Vabis 56 range consists of five four-wheelers and four six-wheelers. Both types have a maximum trainc.34 weight rating of 25 metric tons, the respective solo rating being 12-6 and 16-6 metric tons. The six-wheelers ar single-drive machines with rocker-beam suspension for th trailing wheels. All have normal control, of courst Scania-Vabis's only forward-control goods model bein the LB76, a test report of which was published in ou August 2 issue. The 13-ft. 9-in.-wheelbase vehicle which I tested ha a perfectly standard specification apart from the provisio of a two-speed axle, and was equipped with the standar cab. The tyres at front and rear were 10.00-20 (12-ply and the body was a Zettersbergs 6-cu.-yd. assembly wii single underbody ram and three-way tipping operation.

This body, which was basically of timber constructio with a steel-channel sub frame, was 11 ft. 9 in. lom 7 ft. 10 in. wide and 1 ft. 10 in. deep, and an interestin feature about it was the provision of an air-operated tai gate lock which could be controlled from the cab. Whil!

ais meant •that the driver could tip single-handed without :aving his seat, it would still most probably mean him etting out before moving away after tipping in order to lear away loose material from the rear of the body to how the gate to close properly.

The unladen weight of 6 tons was split almost equally vet the two axles, and with 6 tons 7.5 cwt. of gravel in le, body the rear-axle loading was increased to 8 tons 1 cwt. tith no one in the cab. With lighter bodywork the pay)ad could obviously have been a clear 7 tons, because le chassis-cab kerb weight of this model gives a body nd payload allowance of nearly 8 tons, whilst with a easonably light, four-wheeled independent trailer the total ayload would be close to 17 tons.

'hree Fuel Tests

The three fuel-consumption tests carried out show that ais D8 engine is little more susceptible to heavy use of le throttle than the size of engine which would normally e employed in a vehicle of this gross weight in Britain. )riving fairly reasonably at up to 33 m.p.h. maximum, le consumption rate was good, whilst fairly energetic riving over the same undulating test route at just over 0 m.p.h. maximum increased the rate by 2 m.p.g., which ; a quite acceptable proportional increase. Under connuous full-throttle conditions the consumption rate tended 3 soar, but the average speed in this case was very high, eing within 2.5 m.p.h. of the L56's maximum speed, and le resulting time-load-mileage factor indicates that the ael economy at high speed is not so bad after all.

The L56's acceleration performance , was good: the and ing-start tests were made twice, once using the high xle ratio and once using low, but slightly better times ,ere obtained with high ratio engaged. Similarly. two ts of direct-drive test were Made, and in this case the )w-axle times were slightly better. Checks of the speeds each of the ratio, combinations showed a good spread, xcept that fourth-high was slightly higher than fifth-low, ut the gearing still gives nine useful ratios.

Hill-climbing tests were made on Tvetabaeken Hill, filch is 0.5-miie long and has an average gradient of 1 in . A non-stop climb lasted 1.75 min., which is longer Ian 1 had expected, although still quite good, and the mest recorded speed was 10 m.p.h., this being while :cond-low was in use for 27 sec. The ascent was made in a ambient temperature of 23°C. (73.5°F.), and the engine)olant temperature increased from its normal value of 4°C. (165 'F.) to 77°C. (170.5F.), a negligible rise.

Gradient restart tests were made on Sankta RagnhildsMan_ which is of 1-in-5-8 severity. Fairly smooth fullironic restarts were made in second-low and reverse-high, rid before each of these tests the handbrake was shown owerful enough to hold the vehicle with a minimum of river effort.

Excessive rear-wheel locking resulted in the stopping 'stances obtained from 20 and 30 mph. being rather disapointing. The tipper was stable enough when coming I rest on the dry surface used for the tests, but the rear heels locked for 15 ft. from 20 m.p.h. and for 40 ft. from m.p.h., marking by the front wheels showing that the ont brakes were doing the right amount of work.

Oseillograph traces showed that the system delay was aly 0-3 sec., and that the maximum line pressure during vie stops was approximately 100 p.s.i., the maximum :servoir pressure being 115 p.s.i. The handbrake stops om 20 m.p.h. revealed excessive rear-wheel locking alsothe order of 31 ft.—but the Tapley meter readings 'tallied show good maximum efficiency. In the case of )th the foot and the handbrakes I feel that reduced .aking effort at the rear wheels would give greatly

iproved overall efficiency. Fade resistance was good, however, a 1-min. descent of Tvetabackerr Hill in neutral with the footbrake applied to hold the speed down to 20 m.p.h. reducing the maximum efficiency by only 0.02g.

The L56 was a bit strange to handle at first because of its ultra-light power steering, which however, is apparently what Swedish drivers like. I found the vehicle tending to wander initially, whilst there was also a tendency for road bumps to affect the steering, but at least the servo did give superb conditions when shunting at low speeds.

Light actuation was also a feature of the clutch, which could easily be depressed by hand, and whilst the gear change was reasonably light too, the lever travel was a bit too great for my liking and the lever was too far to the right. The air-operated axle shift is controlled by a T-shaped knob on the gear lever, and this was very satisfactory to use.

For a normal-control design the degree of engine noise heard in the cab was quite low, and the vehicle could be cruised quite quietly at any speed up to 50 m.p.h., although the engine could make itself heard to no mean degree when accelerating hard.

Progressive Braking

The brakes were pleasant to use under normal conditions, with a fully progressive effect, whilst the handbrake was also easy to use. The suspension was quite satisfactory, despite the absence of dampers, though when cornering as quickly as the light steering would permit, roll could be induced.

So far as the cab was concerned, this was the usual Be-Ge high-quality assembly with good layout of controls, instruments and so forth and very comfortable seating. Ventilation appeared to be adequate, whilst the heating system can be relied upon to be effective enough to deal with the coldest of Swedish winters. The degree of allround vision cannot be compared with that given by a forward-control cab, so can only be classed as fair, but at least the high, broad alligator-opening bonnet does give good accessibility to most of the engine and its auxiliaries, and a fitter can sit on one or other of the front wings and work on the power unit in comfort.

The L5642 as tested, in chassis-cab form, sells in Sweden for £2,860. This is, of course, a high price to pay by British standards for a mere 6/7-ton-payload chassis, but in the light of its construction, comfort, overall performance and ability to operate at 25 tons gross train weight, the L56's price assumes a more reasonable tone. Certainly • Swedish operators are prepared to pay it, judging by the number of 56-series (and their 55-series predecessors) to be seen on Swedish roads.