I n a country where half the population is under 25,

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Irish hauliers have elected another youthful leader after a two-year stint by their first woman president. Because Ireland exports 75% of its produce, it has a Government which recognises hauliers' importance to the export drive and has just delivered a sweeping package of reforms. Much in the

LI, garden would be lovely, g but for one thing. When, they ask, is the UK going to lift its 38-tonne road

cci freight limit which costs LI Irish international

LIJ hauliers 1,000 tonnes a week? Patric Cunnane L crossed the Irish sea to :5 meet hauliers in a determined mood.

t the age of 23 Jimmy Quinn was doing quite nicely, thankyou, managing the cold storage department of a meat packing company. Steady money, steady trade, working in one of Ireland's prime export industries. But every day, while loading trucks for exotic destinations, the thought that he was missing out on some great adventure nagged like an aching tooth. Finally, he decided that security and regular employment wasn't enough. "I didn't want to spend the rest of my life in an office," says the 35-year-old who recently became president of the Irish Road Haulage Association.

In 1983 Quinn sold his car after a friendly bank manager offered him a pound overdraft for every pound he raised. With a truck, a fridge unit and, most importantly, a "sense of adventure", he was off to Europe.

Quinn drove regularly for four years until in 1987 he won a contract with a large Italian meat importer. "We've been serving them ever since," he says.

Having sated his wanderlust Quinn stayed at home to develop the business. He now runs 11 vehicles with eight on Continental work, including Eastern Europe. Italy remains an important market: "A very risky place to do business," says Quinn, who has fitted extra steering locks to his vehicles.

The remaining three units work in Ireland for Guinness; Quinn has 13 trailers in Harp livery.

The firm's largest export customer is the Kepac Group, Ireland's biggest lamb exporter. It sent 1.3 million lambs to France last year, in 1,400 truck loads.

Quinn does not carry livestock and sympathises with some of the arguments against the trade: "With the advent of reefers there should be no need for animals to travel any longer than a driver—nine hours broken by a 12-hour break. The heat in central Europe in summertime is not conducive to animal welfare."

But the rules should not be set by a lunatic fringe, he stresses: "There is market justification for moving livestock over short distances."

Quinn has taken over the two-year mantle of IRHA president from the association's first woman president, Sheila McCabe. What made him stand, and what does he hope to achieve?

"I feel I have something to contribute because I worked in the meat trade as a transport user and am now a transport provider," he says. "Every industry in this country has a strong trade association and there's a need for one in the haulage industry."

He welcomes the Irish Government's decision to introduce continuous licensing and last year's move to extend the international licence from three to five years: "People who have served years in the business should not have to jump the same hurdles at renewal time as complete newcomers."

Beyond that he has an agenda which should occupy a good part of his two years in office, While Ireland permits 40 tonnes on its roads, the UK's insistence on 38 tonnes remains a thorny problem for Irish hauliers crossing to the Continent. Quinn intends to press the issue with the Irish Government and exporters. Irish operators, he says, are losing up to 1,000 tonnes a week.

Closer to home, he wants tougher entry requirements. New operators currently have to prove they have EIR2,000 capital for each vehicle; Quinn wants this figure doubled.

He counter charges that he is being protectionist by saying that this measure will protect drivers tempted to come into the industry when they are offered a vehicle in lieu of redundancy. "At the end of two years they can find themselves deep in debt," he says, "with no job and financial commitments they never bargained for."

Tax is never for from a hauliers' heart and Quinn is angered by the fact that manufacturing and exporting companies pay just 10% Corporation Profit Tax while hauliers and other service companies pay 40%. "We would like all industry taxed on the same basis, say 25%," he says. "The haulier driving a load to an export market is as much a part of the export drive as the manufacturer."

If Quinn changes the Government's mind on this issue, only Jack Charlton will rival his popularity among Irish hauliers.

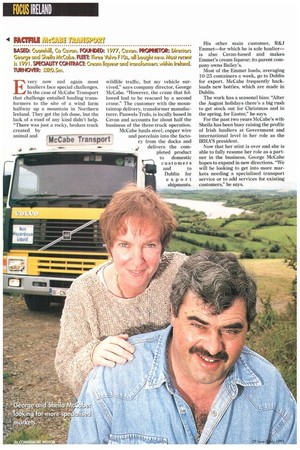

F, 4, very now and again most hauliers face special challenges. In the case of McCabe Transport In the case of McCabe Transport that challenge entailed hauling transformers to the site of a wind farm halfway up a mountain in Northern Ireland. They got the job done, but the lack of a road of any kind didn't help. "There was just a rocky, broken track created by animal and wildlife traffic, but my vehicle survived," says company director, George McCabe. "However, the crane that followed had to be rescued by a second crane." The customer with the mountaintop delivery, transformer manufacturer, Pauwels Trafo, is locally based in Cavan and accounts for about half the business of the three-truck operation.

McCabe hauls steel, copper wire and porcelain into the facto ry from the docks and delivers the com pleted product to domestic customers and to Dublin for export shipments. His other main customer, R&J Emmet—for which he is sole haulier— is also Cavan-based and makes Emmet's cream liqueur; its parent company owns Bailey's.

Most of the Emmet loads, averaging 10-25 containers a week, go to Dublin for export. McCabe frequently backloads new bottles, which are made in Dublin.

The work has a seasonal bias: "After the August holidays there's a big rush to get stock out for Christmas and in the spring, for Easter," he says.

For the past two years McCabe's wife Sheila has been busy raising the profile of Irish hauliers at Government and international level in her role as the TRIINS president.

Now that her stint is over and she is able to fully resume her role as a partner in the business, George McCabe hopes to expand in new directions. "We will be looking to get into more markets needing a specialised transport service or to add services for existing customers," he says.

airy Kirwan ponders the unthinkable.

.LWhat would happen to a large part of , his business if the Irish got fed up with Guinness? "Guinness is focused enough", he replies carefully, "not to allow that to happen." By way of insurance Ireland's brewing giant now includes eight lagers in its repertoire but Roadliner's past and present is inextricably bound up with the creamy black stuff.

As part of Ireland's state transport industry it began life distributing Guinness from railheads to pubs. This it still does, to the tune of 3.5 million kegs a year; about one for every member of the Irish population.

Roadliner remains the biggest single supplier of transport to Guinness but much else about the transport organisation has changed. It is still state owned but a restructuring of its parent company CIE now allows it to compete for business with its original employer, the railways.

In 1987 the Government created three companies reporting to CIE: Iarnrod Eireann, for rail and road freight; Bus Eireann, for crasscountry travel; and Dublin Bus, for the capitars bus service.

Last year larnrod Eireann was restructured into four sectors; engineering, finance, road freight and transportation. Kirwan is general manager road freight, responsible for the Roadliner operation.

"It gives me a commercial advantage to go out and compete with rail freight," he says. Kirwan also competes with other road hauliers and, conscious of the antipathy of some in the private sector, stresses that the operation receives no state subsidies. Profits have risen sharply from £1R60,000 in 1991 to LIR680,000 in 1994.

By Irish standards, Roadliner runs an exceptionally large fleet with 200 vehicles of its own and 200 owner-drivers, 60% of them in dedicated fleets Apart from Guinness, Roadliner's major customers include Irish Cement, Irish Steel, Esso and a variety of general haulage users. A data courier operation calls twice daily on Ireland's four main banks as part of a contract won against competition from Securicor. Although not involved in continental haulage, Roadliner sends up to 80 loads a month into the UK. It owns Rosslare Harbour, in which it has invested ...C1R20m, with the intention of developing backloads brokerage for international operators Kirwan has taken some tough action to change the nature of his operation. Owner-drivers were introduced after Roadliner made 50% of its own drivers redundant. And the reason for the switch? "We are a large state organisation that over the years became inflexible in work practices and the rate for

the 1)1). he

The cutback in employed drivers has not finished. Kirwan wants to introduce contract drivers for more of the fleet while retaining ownership of the trucks. "The market rate for drivers is lower than the rate our drivers get," he points out.

Does he fear a union backlash? "Maybe, but we intend to stay in road freight and compete with others, "he says, adding that the policy will be implemented by not replacing retiring drivers: We don't expect a major problem because of the high age profile of our drivers."

One hurdle not yet crossed is membership of the IRHA. Applications to join have been refused although Kirwan says negotiations continue. "Our aims and the IRHA's aims do not vary much," he says. "We employ many of their members."

Would he like to follow the logical direction suggested by his company's employment practices and move into the private sector? "That's for the Government to decide," he stresses, but since we are operating efficiently within the semi-state sector I see no reason for rimtigc

Food suppliers, if they are to survive, learn to dance to the supermarkets' tune. When supermarkets demanded that meat should be supplied cut into steaks or joints to sell direct to consumers, Irish food suppliers set up plants to do just that

Back in 1984, John Guilfoyle had just gone into business with one truck distributing for a chemicals company when he noticed this trend. He realised there could be an opportunity here because the boning plants were at different locations to the slaughterhouses. And so it proved.

The export market used to consist mainly of hanging carcases but that has changed to concentrate on finished product. It meant less waste: "You can get a lot more saleable meat on board a vehicle in crates," says Guilfoyle.

Much of this meat is exported, but Guilfoyle's involvement remains entirely domestic, delivering carcasses to boning plants and removing boned meat to other locations such as wholesalers and canneries.

From a single vehicle in 1984, Guilfoyle now runs 20 Scania tractors and 50 reefers, so the supermarkets' demands have done him a favour. He also transports bulk feeds, including malt to Guinness. (Does anyone in Ireland not work for Guinness? Silly question). Guilfoyle is pleased that the Irish Government is introducing consignor liability: He believes it will eliminate a great deal of overloading, because consignors will not want to be caught out. "It is grossly unfair that you could pick up a sealed load of beef from a factory, go down the road and get caught," he says. "There's no advantage to a haulier to overload because loads are priced by consiginent, not by the tonne."

Like most Irish hauliers, he has problems with Irish roads: "The roads around major cities are good but as for the secondary roads...it's as if the rest of the country didn't exist. We don't get half as much work done in Ireland as a haulier in the UK because of the roads."

He's built up a profitable sideline importing trailers and tractors from the UK. At first he used (M's classifieds— "it was a fantastic help to me"—but he's also built up his own contacts.

Like noting the transport needs of the boning plants, it was a case of spotting an opportunity. As he says, "There's a very big demand in Ireland for a modern secondhand trailer."

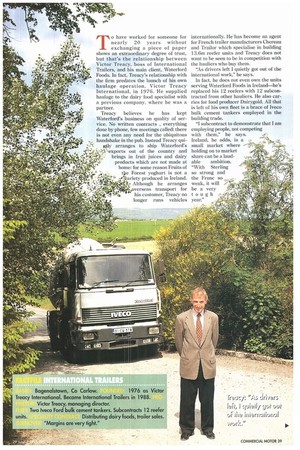

Guilfoyle: "There's no advantage to a haulier to overload." To have worked for someone for nearly 20 years without exchanging a piece of paper shows an extraordinary degree of trust, but that's the relationship between Victor Treacy, boss of International Trailers, and his main client, Waterford Foods. In fact, Treacy's relationship with the firm predates the launch of his own haulage operation, Victor Treacy International, in 1976. He supplied haulage to the dairy food specialist with .4a previous company, where he was a partner.

Treacy believes he has kept Waterford's business on quality of service. No written contracts , everything done by phone, few meetings called: there is not even any need for the ubiquitous „.,. handshake in the pub. Instead Treacy quiregy arranges to ship Waterford's 1-exports out of the country and 4,1,•,if::: : brings in fruit juices and dairy ,....,,„,..„,e.... .1.products which are not made at home: for some reason Fruits of ttte Forest yoghurt is not a -Okariety produced in Ireland. . .. Although he arranges verseas transport for his customer, Treacy no longer runs vehicles internationally. Hellas become an agent for French trailer manufacturers Chereau and Trailor which specialise in building 13.6m reefer units and Treacy does not want to be seen to be in competition with the hauliers who buy them.

"As drivers left I quietly got out of the international work," he says.

In fact, he does not even own the units serving Waterford Foods in Ireland—he's replaced his 12 reefers with 12 subcontracted from other hauliers. He also carries for food producer Dairygold. All that is left of his own fleet is a brace of Iveco bulk cement tankers employed in the building trade.

"I subcontract to demonstrate that I am employing people, not competing with them," he says. Ireland, he adds, is a •• small market where :t holding on to market share can be a laud• 4412 able ambition. • "With Sterling • • ,

so strong and the Franc so weak, it will -74r be a very ,;,• • tough ...

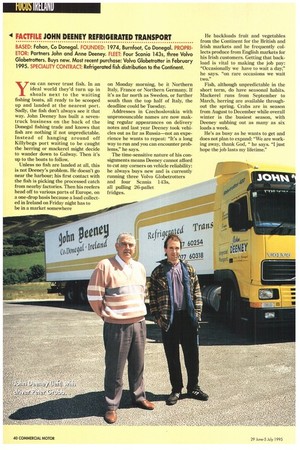

year." you can never trust fish. In an ideal world they'd turn up in shoals next to the waiting fishing boats, all ready to be scooped up and landed at the nearest port. Sadly, the fish don't always see it that way. John Deeney has built a seven truck business on the back of the Donegal fishing trade and knows that fish are nothing if not unpredictable. Instead of hanging around off Killybegs port waiting to be caught the herring or mackerel might decide to wander down to Galway. Then it's up to the boats to follow.

Unless no fish are landed at all, this is not Deeney's problem. He doesn't go near the harbour; his first contact with the fish is picking the processed catch from nearby factories. Then his reefers head off to various parts of Europe, on a one-drop basis because a load collected in Ireland on Friday night has to be in a market somewhere on Monday morning, be it Northern Italy, France or Northern Germany. If it's as far north as Sweden, or further south than the top half of Italy, the deadline could be Tuesday.

Addresses in Czechoslovakia with unpronouncable names are now making regular appearances on delivery notes and last year Deeney took vehicles out as far as Russia—not an experience he wants to repeat: "It's a long way to run and you can encounter problems," he says.

The time-sensitive nature of his consignments means Deeney cannot afford to cut any corners on vehicle reliability: he always buys new and is currently running three Volvo Globetrotters and four Scania 143s, all pulling 26-pallet fridges. He backloads fruit and vegetables from the Continent for the British and Irish markets and he frequently collects produce from English markets for his Irish customers. Getting that backload is vital to making the job pay: "Occasionally we have to wait a day," he says. "on rare occasions we wait two."

Fish, although unpredictable in the short term, do have seasonal habits. Mackerel runs from September to March, herring are available throughout the spring. Crabs are in season from August to December while overall winter is the busiest season, with Deeney subbing out as many as six loads a week.

He's as busy as he wants to get and does not plan to expand: "We are working away, thank God, "he says. "I just hope the job lasts my lifetime."

LIMERICK

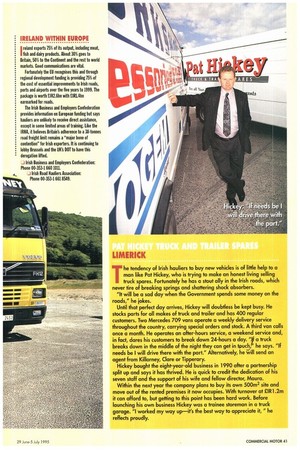

The tendency of Irish hauliers to buy new vehicles is of little help to a man like Pat Hickey, who is trying to make an honest living selling truck spares. Fortunately he has a stout ally in the Irish roads, which never tire of breaking springs and shattering shock absorbers.

"It will be a sad day when the Government spends some money on the roads," he jokes.

Until that perfect day arrives, Hickey will doubtless be kept busy. He stocks parts for all makes of truck and trailer and has 400 regular customers. Two Mercedes 709 vans operate a weekly delivery service throughout the country, carrying special orders and stock. A third van calls once a month. He operates an after-hours service, a weekend service and, in fact, dares his customers to break down 24-hours a day. "y a truck breaks down in the middle of the night they can get in touch/ he says. "If needs be I will drive there with the part." Alternatively, he Will send an agent from Killarney, Clare or Tipperary.

Hickey bought the eight-year-old business in 1990 after a partnership split up and says it has thrived. He is quick to credit the dedication of his seven staff and the support of his wife and fellow director, Maura.

Within the next year the company plans to buy its own 500m2 site and move out of the rented premises it now occupies. With turnover at £1R1.2m it can afford to, but getting to this point has been hard work. Before launching his own business Hickey was a trainee storeman in a truck garage. "I worked my way up—it's the best way to appreciate it," he reflects proudly.