Agricultural Oil Tractors.

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Up to a couple of years ago, not more than half a dozen nianufacturers in this country had given any serious attention to the design and construction of internal combustion-engined tractors, and of those few two or three only had produced machines which, by any stretch of imagination, could be considered first-class examples of British engineering skill. To-day, however, there are at least three times that number of British concerns which have built, or are prepared to build, serviceable agricultural motors, and at least. one company has found the demand so great, that, in order to cope with the trade, it has built a magnificent new works and added an important department to an already-extensive factory and business organization, solely for the making and erecting of farm motors. What is true of the oil-tractor industry in this country is equally true of the other side of the herring pond. United States tractor builders are fully alive to both the immediate and potential importance of the Canadian and Colonial markets, but it cannot be said that they are producing machines which meet present-day requirements. Rome manufacturers, too, while producing more-soundly-built machines than the Americans, are, in most cases, lacking in a true perception of the farmers' needs. There is a reasonable show of enterprise among certain builders, but the majority of them lack either the capital or the necessary " ginger " to force the sale and use of their products. This year's Royal Show, gives indientions of an awakening by several makers. Simplicity and Sturdiness.

Simplicity and sturdiness should be the keynotes in the design of a farm engine. The lessons which have been learned in motor-vehicle practice, unless they be judicially blended with the ideas of practical agricultural engineers--and how few of the latter class are to be found on this side of the Atlantic— are of no avail. It is of no use to argue that what is good practice in a petrol wagon for a five-ton load should be equally valuable if embodied in a five-ton tractor. It should be remembered that a tractor works under entirelydifferent conditions: a wagon carries the load, and, consequently, it rarely fails through lack of adhesion if its wheels are shod with rubber tires, and only under certain conditions will they fail to grip.

even if they are fitted with steel tires ; the wheels of a tractor, which class of machine, however, does not curry but hauls its load, may easily be skidded, and they frequently are so treated by both experienced as well as careless drivers. We have often heard the wail of a farmer who, having recently purchased an agricultural motor, begins to experience trouble with its parts as soon as the maker's expert driver has left the machine in charge of a farm hand—an excellent agriculturist, perhaps, but by no means a mechanic. The time may not be far distant when, with the rapid increase in the use of machines on the farm, all farmers will become agricultural engineers, but, until that time arrives, it will be better for tractor builders to sacrifice a little in the economical working of their motors, rather than to complicate the machines in order to reduce the fuel bill by a fraction of a gallon per acre. It were, again, better to take off a part, rather than to add a new one. One of our oldest and most practical of road-engine builders, in reply to an inventor who desired to arouse his interest in some fuel-saving device, once replied : "I do not want to look at anything which has to be put on to my engines, but if you can show me what I can take off, I will pay you well for your advice."

The Need ?or Agricultural Motors on the Farm.

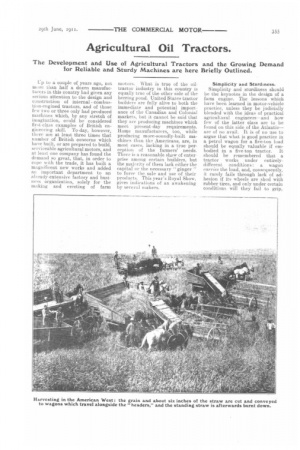

In our last week's issue, we reproduced an interesting photograph which showed a machine known in Canada as a "combine," which is capable of cutting and threshing 40 acres of grain per day, and delivering it in sacks from the side of the machine. That picture gave a graphic idea of the large army of men and horses which are required for the operation of such a machine. A 50 ler), oil tractor, if used for the

hauling of such a machine, would displace 40 horses and all but three or four of the men, and it would, in addition, do more work per day. A further photograph, reproduced herewith, shows a number of " headers " working in the American West. The illustrations mentioned are but two pictorial exemplifications of the great and growing need for mechanical haulage of farm implements, a need that is daily becoming more acute, because of the tendency for agricultural labourers to desert the country for the town. If the men go, they must be replaced by labour-saving devices. There will, in the future, be a much-more-extensive application of both steam and oil-engined tractors for farm work, particularly for ploughing purposes, the cost of which operation, in many parts of the world, represents about onefourth the entire cost of raising the

crop. Ploughing calls for powerful means of haulage, and for strongly made ploughs. Motor manufacturers and implement makers have done much for the farmer in the past. and they are still making every effort to produce machines which will enable him to work his land more profitably. Jethro Tull. an old English gentleman, who farmed a large estate in Berkshire about the year 1700, maintained that tillage was as good for the land as the application of manure, if not better. Tull'a views. however, do not coincide with those of modern scientific farmers, but there is no doubt that the thorough tillage of the land, at the right time of the year and under suitable weather conditions.. greatly assists it to recuperate after it has yielded a heavy crop. Horse haulage. for that purpose, is very costly, and the available season is far too short to permit of the thorough working of the ground by implements which are hauled by animal power.

In many countries, particularly in the Argentine and South Africa, the available number of animals is much too small to cope with the work which should be performed within a given time. Further, disease or the lack of fodder, along the tracks which connect the farm— stock or produce—with the nearest market or port, account for the neglect of many thousands of acres of rich land, which, by the aid of motor-haulage methods could be rendered profitable. In the Argentine, sheep farmers now send wool to the coast by bullock wagons, across hundreds of miles of pampasgrass-covered land, amid which there is little water and practically no forage. In Africa, transport bullocks are dying by the thousand each year, through the ravages of the tick --a dreaded insect—and the scarcity of grazing land beyond the coastal belt.

There are many economical reasons for the application of mechanical haulage and tillage, and not the least important of these is that, in Canada, there are three persons in the towns to each one on the farms, whilst, in England, the proportion is probably very much greater. The result is that each man on the land must on the average produce enough food stuff for four to six of his fellow beings.

Steam or Oil?

We cannot, in this article, discuss the relative merits of steam engines and oil engines as prime movers for farm motors. Each class will always have its advocates, but, for geographical and topographical reasons, the oil-engined tractor will find the more-extensive employa ment, especially in the Argentine, in Australia, the American West, Canada, Russia, and many other countries where oil, in some districts, is more plentiful than water. Other countries suffer from a lack of solid fuel. So scarce is water in some parts of Canada, that paraffin, or kerosene as it is there called, is employed for cooling purposes in the cylinder-jackets and radiators in place of water, whilst, in the American West, the use of crude oil as a cooling medium is quite usual.

With a well-designed internalcombustion motor, the rate of evaporation of the cooling liquid is very low, and enough fuel and water can be carried upon the tractor itself for from one Co five days of hard work in the field. This is a point which greatly affects the working costs of a farm engine. Under certain conditions. a steamer rnay be run at a much-lower cost than an oil tractor, but the economical working of a steam engine depends upon its close proximity to supplies of water and coal ; if both must he transported to the field of operations from a distance of a few

miles, and in some countries it might be a few hundred miles, the working costs of a steamer must compare unfavourably with those of an oil tractor. A given quantity of liquid fuel may be transported much more readily, and at less cost, than an equivalent quantity of solid fuel, but, even if liquid fuel burners were successfully applied to the furnaces of steam tractors, there still remains the difficulty of water supplies.

What a Farm Motor Can Do.

What can a motor do on a farm? The answer is, anything that can be done by horses—and a good deal more. Ploughing can be performed by oil motors, at a lower cost than by any other means. Apart from ploughing, such a motor may be used for the haulage of rollers, clod-breakers, discs, cultivators, harrows, reapers, mowers, headers, combines, trucks, etc., and as a portable power plant for driving farm machinery, such as threshers, inaize-sliellers, crushers, pumps, and, in fact, anything which requires power for its driving. True. for some of these operations, a motor may be wasteful of power, but so is the horse. For the reclaiming of land, for drainage operations, irrigation purposes, the haulage of timber and materials for road-making, building, fencing, etc., an oil tractor may prove equally useful. Tracts of rich but sloping land, down which the soiI is washed away by heavy rains, may. by enlisting the services of an oil tractor for the transportation of the necessary materials, and by terracing the land in the manner which is practised by the wine-growers along the banks of the Rhine and in many other parts of the Continent, be made suitable for the growing of crops. In Nyassaland. drv-irriga tion methods are employed on the rubber plantations ; the land is regularly and frequently scarified. so as to maintain a thick layer of dust, which dust prevents the rapid evaporation of moisture after heavy rains and the formation of deep fissures in the earth. This operation can be done by motors much more effectively and cheaply than is at present achieved by muledrawn or ox-hauled implements.

These are but a few of the uses to which oil tractors may profitably he applied. They can displace every horse on a farm, except those which the farmer cares to keen for personal exercise and enjoyment. An English farmer once said to the writer, during an argument on the ultimate supersession of the horse for heavy work on the farm : "Yes, motors can do the work both onicker and better than horses, but they don't make manure." True, but they save the farmer BO much, both in time and money, that he can afford, quite apart from the

superior tillage secured, to manure his land by other means, either by chemicals or by breeding or dealing with other stock—sheep, cattle, or pigs, all profit-making animals.

Costs of Operation.

A 20 li.p. oil tractor may be operated in Canada at an inclusive cost of 62s. 6d. per day, which cost is made up as follows : one gallon of petrol for starting purposes, is. lid. ; 22 gallons of paraffin, or kerosene, at 80., las. 7d. ; driver's wages and board, 14s. .6d. ; daily proportion of cost for the haulage of fuel once a week at a total cost of 12s. 6d., 2s. id. ; depreciation, interest and repairs, 29s. 20. This engine, with a five-furrow plough, can break 10 acres a day at a cost of 6s. 3d. an acre ; on stubble land, the engine would not consume nearly so much fuel in the day's work, on account of the lighter drawbar pull, and, moreover, as the tractor would travel at a slightlyhigher speed, more land could be cut in the same time, the cost per acre working out at 4s. 3d. The same outfit can drive a threshing machine, which is capable of dealing with 2,000 bushels of oats or 1,000 bushels of wheat per day, and the saine motor, with suitable cultivators, could deal with from 40 to 61) acres a day. The figures here given are the average of those actually obtained by an owner in Manitoba.

With a high-powered machine, more economical results could be obtained. Take the English-made Marshall tractor of 30 b.h.p. Trials made in England, under the writer's observation, in November, 1907, showed that that machine was capable of ploughing an acre in 634 minutes, cutting six furrows 10 in. wide and from 5 in. to 6 in. deep. Some 21A acres were cut during the

test, at a total cost of £3 as. 4W., which is made up as follows : 44 gallons of paraffin at 6d., LI 2s. ; two gallons of petrol at is., 2s. ; gallons of lubricating oil at is. 6d., 2s. 3d. ; grease, waste, etc., is. 6d. ; cartage of water, 2s. ; ploughman's wages, 12s. 4d. ; driver's wages, 16s. 4d. ; depreciation at 20 per cent., 5s. 6d. ; interest on capital outlay at five per cent., Is. 5d. ; or a total cost of 3s. old. per acre. Still-lower figures could be obtained by using large gang ploughs and more-powerful motors, but the powers already quoted are such as could be made useful on any farm of average size. Machines are now made, up to 80 h.p. and 100

which are capable of hauling gang ploughs cutting from 15 to 20 furrows.

We may take, as examples of smaller machines than those quoted, The Ivel machines, with two-cylinder engines developing from 16 h.p. to 18 h.p., which motors competed in the R.A.S.E. trials, at Baldock, in August last ; they clearly demonstrated that they were capable of operating three-furrow ploughs and of cutting only slightly less than one acre an hour, at a total cost of under 4s. 6d. per acre. The average depth ploughed was a in., and the drawbar pull varied from 728 lb. to 896 lb. It is quite true that these trial results were obtained by drivers who knew their respective machines thoroughly, and who handled them intelligently, but equally-good results may be obtained by any man who takes the business seriously, and who handles his machine with a reasonable amount of care.

It is not to be expected that the type of driver who maintains that " oil is oil," and who persists in using any and every kind of available oil for the lubrication of the cylinders, etc., irrespective of its quality, will get such good results as does the man who " feels " for his machine. Use the oil-can freely is a good maxim for the driver of an agricultural oil tractor, but he should be sure that the said can con tains a suitable oil, although not necessarily one with a fancy name.

Conclusion.

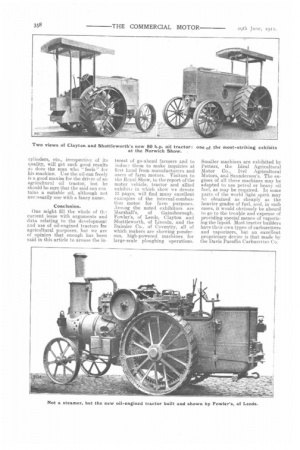

One might fill the whole of the current issue with arguments and data relating to the development and use of oil-engined tractors for agricultural purposes, but we are of opinion that enough has been said in this article to arouse the in terest of go-ahead farmers and to induce them to make inquiries at first hand from manufacturers and users of farm motors. Visitors to the Royal Show, to the report of the motor vehicle, tractor and allied exhibits in which show we devote 13 pages, will find many excellent examples of the internal-combustion motor for farm purposes. Aincng the noted exhibitors are :rfarshall's, of Gainsborough, Fowler's, of Leeds, Clayton and Shuttleworth, of Lincoln, and the Daimler Co., of Coventry, all of which makers are showing ponderous, high-powered machines for large-scale ploughing operations.

Smaller machines are exhibited by Petters, the Ideal Agricultural Motor Co., Ivel Agricultural Motors, and Saunderson's. The engines of all these machines may be adapted to use petrol or heavy oil fuel, as may be required. In some parts of the world light spirit may be obtained as cheaply as the heavier grades of fuel, and, in such cases, it would obviously be absurd to go to the trouble and expense of providing special means of vaporizing the liquid. Most tractor builders have their own types of carburetters and vaporizers, but an excellent proprietary device is that made by the Davis Paraffin Carburetter Co.