Economical, Speedy and le to Drive

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

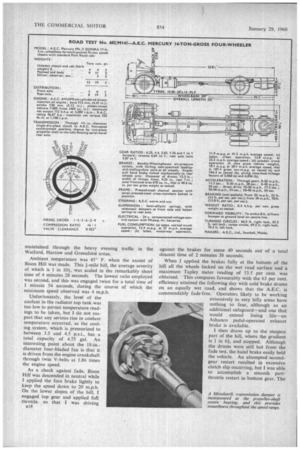

ATEST of one of the latest. A.E.C. Mercury fourwheelers made it easy to understand why this model has remained one of the most popular of its type since its introduction over sii years ago. It is particularly suited to British haulage conditions with payloads of at least 9 tons, as it has a high-powered engine which endows the vehicle with good hill-climbing properties, aboveaverage acceleration and a useful maximum speed of 45 m.p.h.

The Mercury is economical, too. When tested under simulated trunk-operation conditions 13.4 m.p.g. was returned, whilst town running dropped this figure by only 0.6 m.p.g. Full-speed operation on a stretch of motorway gave the highly commendable result of 11.9 m.p.g. at an average speed of 41.2 m.p.h., yielding a time-load-mileage factor of 6,856—a particularly high figure for a 14-tongross vehicle.

Unchanged But Smart Although the cab styling has not been changed since 1953, the vehicle is still smart by current standards.Admittedly, certain interior refinements are missing when compared with contemporary cabs, but it is obvious that little design work or money would have to be spent on the basic Park Royal assembly to bring it fully up to date.

General handling sets a high Standard, and it is a pleasant vehicle to drive under all traffic conditions. The combination of a 112 b.h.p. engine and five-speed synchromesh gearbox gives all the liveliness that could be asked for. The steering is particularly fight, although because of its ratio of 40 to 1 the number of turns of the wheel from lock to lock might be thought excessive. In fact, the hand work involved never becomes too much.

The Mercury range is at present split into two basic categories, Marks I and 11. The Mk. I models are similar to the original versions introduced in 1953 in that they are rated for a gross weight of 12 tons, which permits a payload of about 71 tons. The Mk. II models have a 14-ton gross-weight rating, the unladen weight giving a body and payload allowance of 9f tons, including driver and passenger.

Basically, there is little technical difference between the two types, although the four wheelbases offered for the Mk. I differ from the three wheelbases of the Mk. II B16 versions. Furthermore, the Mk. I chassis have an overall width of 7 ft. 6 in., whilst the Mk. II is 7 ft. 84. in. wide. -The short-wheelbase Mk. I is fOr use as a tractive unit at a gross train weight of IS tons..

The licensing weight of the 2GM4RA 17-ft. 3-in.wheelbase chassis is 3 tons 151 cwt. and the standard Park Royal cab adds 3f cwt, Thus even with the lightest of light-alloy platform bodies the taxation weight of a complete Mercury Mk. II will exceed 4 tons, thereby allowing the use of 8-ft.-wide bodywork under-the present regulations_ The chassis-cab outfit offered to me for test had a kerb weight of 4.. tons 41 cwt and weights totalling 9 ions 11* .cwt had been securely bolted to two channelsection pressings, whith in turn were firmly attached to the chassis frame. The gross weight with an A.E.C. driver and myself aboard was 13 tons 191 cwt., and the rear-axle lOading WasWithiti4 emit: Ortlie'-inaxiinurri legal limit of

9 tons. . _

Misty, damp weather, which persisted throughout the two 'days of testing, made conditions fat from ideal, particularly so far as the retardation figures were concerned. A fuel-consumption run was carried out first over a 10-mile put-and-return strefch of the. Western _Avenue dual carriageway. AlthOugh. traffic was reasonably light, this is • not a, particularly -easyroute, as there 'are nine roundabouts •to negotiate, but an average speed of 27 m.p.h. was maintained and the resulting consumption rate of 13.4 m.p.g. can be considered highly satisfactory. . Acceleration tests followed, and commendable liveliness was shown from rest to 40 M.p.h. For these standing start tests, second, third, fourth and top gears were employed, third giving a road speed of 16 m.p.h. and fourth, 29 m.p.h. Good direct-drive times were recorded. The acceleration rate in this ratio was remarkably consistent up to 30 m.p.h., with only a slight fall-off up to 40 m.p.h. Both of these sets of times show the consistency of acceleration up to

within 5 m.p.h. of the maximum speed, a feature which stresses the good torque characteristics of the AVU470 engine.

I decided to make hill-climbing tests on Bison Hill, Whipsnade, and, because a Petrometa had been fitted into the fuel circuit, fuel-consumption figures were taken while driving between Denham and Whipsnade.

The route chosen was via Watford, the North Orbital Road, MI as far as A505, and Dunstable. This route totalled 29 miles and was completed at an average speed of 28.5 mph., whilst the fuel-consumption rate was 12.2 m.p.g. This figure is good, but is even better when it is realized that 12 of the 29 miles were spent on MI at full throttle. This distance was covered at 41.2 m.p.h. average speed and at a consumption rate of 11.9 m.p.g., as indicated by the Petrometa.

After the gradient tests the return to Southall was made via St. Albans, Watford and Harrow, but without using MI. The total distance was again 29 miles, although, because of heavy traffic, the average speed was reduced to 25.1 m.p.h. The fuel consumption was improved on the return run. A figure of 12.8 m.p.g. was returned, which is surprising in view of the comparatively high average speed maintained through the heavy evening traffic in the Watford, Harrow and Greenford areas.

Ambient temperature was 45° F. when the ascent of Bison Hill was made. This I-mile hill, the average severity of which is 1 in 101, was scaled in the remarkably short time of 4 minutes 28 seconds. The lowest ratio employed was second, and this was engaged twice for a total time of 1 minute 54 seconds, during the course of which the minimum speed observed was 4 m.p.h.

Unfortunately, the level of the coolant in the radiator top tank was too low to permit temperature readings to be taken, but I do not suspect that any serious rise in coolant temperature occurred, as the cooling system, which is pressurized to between 3.5 and 4.5 p.s.i., has a total capacity of 4.75 gal. An interesting point about the l8-in.diameter four-bladed fan is that it is driven from the engine crankshaft through twin V-belts at 1.86 times the engine speed.

As a check against fade, Bison Hill was descended in neutral while I applied the foot brake lightly to keep the speed down to 20 m.p.h. On the lower slopes of the hill. I engaged top gear and applied full throttle. so that I was driving against the brakes for some 40 seconds out of a total descent time of 2 minutes 38 seconds.

When I applied the. brakes fully at the bottom of the hill all the wheels locked on the wet road surface and a maximum Tapley meter reading of 53.5 per cent, was obtained. This compares favourably with the 63 per cent. efficiency attained the following day with cold brake drums on an equally wet road, and shows that the A.E.C. is commendably fade-free. Operators likely to be working extensively in very hilly areas have nothing to fear, although as an additional safeguard-and one that would extend lining life-an Ashanco pedal-operated exhaust brake is available.

I then drove up to the steepest part of the hill, where the gradient is 1 in 6-1, and stopped. Although the drums were still hot from the fade test, the hand brake easily held the vehicle. An attempted second gear restart resulted in excessive clutch slip occurring, but I was able to accomplish a smooth part throttle restart in bottom gear. The maximum gradient ability with the 5.87-to-1 axle ratio fitted to the test vehicle approaches 1 in 4, which should be ample for most purposes. An alternative ratio of 6.28 to 1 could be fitted if required, whilst there are higher ratios of 5.22 and 4.7 to 1.

I postponed making the braking tests until the second day in the hope that the rain might stop, but I was unlucky, so had to conduct my tests on a streaming wet road. The figures obtained, therefore, did not bear much resemblance to the braking efficiency which would have been obtained on a dry surface. All the wheels locked when stopped from each speed, producing 20-ft. skid marks from 20 m.p.h. and 40-ft. skids from 30 m.p.h. An average Tapley meter reading of 63 per cent. was recorded from each speed, and the Mercury pulled up in a straight line on each occasion despite the locked wheels.

Although a treadle brake pedal is employed, its action is not as harsh as is sometimes encountered with this type and a fairly progressive " feel " is retained, even when travelling light.

st 16 m.p.g. in Service

The test weights were then removed but the supporting channels were left in place on the chassis frame, so that an unladen fuel-consumption test could be conducted. This run was made at a gross vehicle weight of 5 tons—slightly heavier than would have been the case had a light-alloy platform body been fitted. The test was carried out over the same 10-mile stretch of the Western Avenue as had been used for one of the laden runs and a consumption rate of 18.1 m.p.g. at 28.1 m.p.h. average speed was obtained. This is a very good figure and indicates that operators working laden in one direction only could expect at least 16 m.p.g. overall from a Mercury Mk. II.

Suspension reached a high standard, helped partly by the telescopic dampers fitted as standard on the front axle. They reduced cab bounce when running empty and the handling characteristics did not alter much whether laden or unladen.

Particularly when running on the governor, engine noise in the cab was excessive. Most A.E.C. power units seem to suffer from this defect, however, and much of this sound could be absorbed by using a quilt on the engine cowl. When running on the motorway at maximum speed no engine, gearbox or imopeller-shaft vibrations were noted. The Metalastik transmission damper incorporated in the propeller-shaft centre bearing undoubtedly helps in this respect. No undesirable steering characteristics were noted on the motorway. The gear-change is first rate, the short lever travel and effective synchromesh_ helping to make gear-changing alrnost a pleasure.

Cab Criticism The cab interior does not bear favourable comparison with the latest Park Royal cab made for A.E.C. Mammoth Major Mk. V eight-wheelers, which,among other things, have entrance steps ahead of the front wheels. The driving position is good and the 'pedals, steering wheel and gear lever are well placed, but such features as a single windscreen-wiper blade, front quarter lights which cannot be opened, a single rear window and balanced-drop door windows (which are extremely Stiff to operate) could well be improved. An efficient heater is desirable standard equipment in a steel-panelled cab such as this.

Because of delays caused by unfruitful waiting for dry roads there was no time left to conduct maintenance tests. The maintenance procedure associated with an A.E.C. Mercury was, however, dealt with in the test report of a Mercury tractor unit published in The Commercial Motoron March 25, 1955.