RUNNING A SIX-WHEELER ON PRODUCER-GAS.

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Results of an Instructive Test of a Guy Lorry Equipped with a Tulloch-Reading Gas Producer.

NOWHERE in the world is cheap and efficient transport by road or across country more important than in our Colonies and Dominions, where main-line railways are usually few and the distances between them great The employment of vehicles running on petrol is often prohibitive, for the reason that the fuel is so expensive, and, consequently, hulk produce cannot. be handled at an etionomical figure.

With the advent of the vehicle running on prodncer-gas as fuel the whole outlook has been altered, and with satisfactory producers using cheap, native-made charcoal, or; in some cases, even the raw wood, the running costs per ton-mile can actually be made lower than is normally obtainable at home.

Automatic Producer Required.

The great point is to utilize a producer which is practically automatic in action, so that the vehicles can be controlled by men having but little skill. The apparatus must also provide a clean, dry, dust-free gas which will permit an engine to be run-for long periods without decarbonizing being necessary. When first produced, the main difficulty was the long time involved in starting from cold, but in the latest types this annoying factor has been reduced until it is almost negligible. Similarly, any stops of more than a few minutes' duration formerly involved an extended blowing-up of the fire, but here, again, restarting can be made, even after a stop of half an hour or more, almost with the same ease as in the case of the engine running on petrol. As an example of what can be done with a modern form of producer, we may refer to some particularly interesting and instructive trials which were recently 'carried out with a Guy rigid Nix-wheeler employing the TullochReading gas-producer.

They were run in England under the aegis of the Empire Cotton Growing Corporation prior to the shipment of the vehicle to Nigeria, and an independent authority, whose name we are not at present permitted to divulge, was invited to deal with the matter.

Tests were carried out on road and cross-country tracks, with and without a trailer, the weather conditions being fine during the rfmning on the road, but wet in general while cross-country work was being done.

To afford a good idea of the behaviour of the Guy vehicle, it will first be necessary to give a few details of it.

The engine has six cylinders of 4i ins, bore and 5-i ins. stroke, giving an R.A.C. rating of 43.3 h.p., the gear ratios being :—Top, 1 to 1; third, 1.122 to 1; second, 2.5 to 1; first 4 to 1; reverse, 3.86 to 1; there was also an auxiliary gear of 1.985 to 1, whilst the final-drive ratio to the two axles was 9.33 to 1. The total weight of the lorry was 8 tons 12 cwt., and that of the trailer with its 2-ton load was 3 tons 12 cwt. 1 qr., the total useful load carried and towed being 5 tons.

Conducting the Tests.

Prior to each test, the fuel hopper, water tank and petrol tank were filled to a definite level. The road test comprised 202.1 miles with a trailer and 81.5 miles without a trailer, the lorry being laden with 3 tons for 40.75 miles, and for an equal distance with 4 tons.

With the trailer the lorry pulled well, and on the level themaximum speed of 20 m.p.h. was easily attained. On hills the drag of the trailer made it necessary soon to change to a lower gear, but it was noticed that by changing down to first gear early a hill could be climbed more rapidly than by remaining in third and second gears for longer periods. It should be noted that an engine governot was employed, cutting in at a maxi mum of 20 m.p.h., but it appearee rather slow in cutting out, and before acceleration of the engine could be fell again, the speed wauld drop to 15 m.p.h and sometimes even to 12 m.p.h.

Some Excellent Results.

One involuntary stop occurred through an obstruction in the fuel-feed valve, but to remedy this the whole valve was removed, cleaned and replaced and the engine restarted within 10 minutes. On three occasions, when pulling hard on a hill, the engine failed through loss of power. This appeared to have been caused by poor-quality gas, for in the time taken to restart on petrol and to Switch over to gas (two to three minutes) the fault had rectified itself.

With the trailer, the fuel consumption proved to be 3.1 lb. per mile ; water, 9.6 mpg.; petrol, 101 m.p.g. (being used for starting and emergencies only)'; average speed, 11.8 m.p.h. Without the trailer, the fuel consumption

Was 2.8 lb. per mile ; water, 23.3 m.p.g.; petrf, nil ; average speed, 12.6 m.p.h.

In the cross-country tests the route comprised rough roads, sandy and muddy tracks, heather, gorse and grassland. Here the vehicle ran 419.5 miles, of which 136.8 miles were with a trailer and 282.7 miles without. The vehicle performed very well, but with the trailer it was necessary to engage the emergency low gear to climb a number of the steep hills an the crosscountry course. On favourable ground 20 m.p.h. could be attained, but 6 m.p.h. was the average over a stretch of heavy sand. In boggy ground the vehicle became ditched, but when the trailer was unhooked it was able to extricate itself under-its own power, using gas.

A. gradient of 1 in 5 was climbed on a grassy slope without the trailer. On a 1 in 4+ gradient the machine climbed three-quarters of the way and then stalled through the wheels becoming locked in loose ruts. After reversing Into a more favourable position on the same gradient the climb was completed. When pulling hard in first gear in deep sand the engine did not overheat, the highest radiator temperature being 149 degrees F., with the atmospheric temperature at 57 degrees.

Three stops occurred on hills through loss of power, but restarting on petrol and switching over to gas solved the P roblem.

. The Drawbar-pull Teats.

In a drawbar-pull test the lorry, carrying 3 tons of iron ballast and fully equipped, towed a tractor with a weight of 7 tons 18 cwt., using tho Watson dynamometer. On wet tar-macadam the tractor, having both brakes on and the vehicle being in the low-reduction gear, a pull of 6.500 lb. was registered. The vehicle, although running on gas, did not stall, but pulled the tractor along the road with its wheels locked. It is .obvious that the actual drawbar pull could have been much greater than that registered.

In the cross-country tests the results were as follow :—With trailer, fuel, 4.6 lb. per mile; water, 17.6 m.p.g.; petrol, 54.7 m.p.g. ; average speed, 7.3 m.p.h. Without trailer, fuel, 4.4 lb.

per mile; water 13.1 m.p.g. ; petrol, 40.1. ; average speed, 11.4 m.p.h.

No difficulty was experienced in maintenance. Replenishment of the hopper and the water tank, and cleaning the cyclone dust extractor and scrubber, drawing the fire and emptying the ashpan were carried out daily, but proved to be quite simple. Lighting the fire, producing the first supply of gas, starting on petrol and switching over to gas averaged 10 minutes.

The fuel delivered with the vehicle gave better results than that obtained in London ; the latter made it necessary to empty the cyclone and clean two scrubbers after 50 miles. With _goodquality charcoal pure ash could be obtained from the cyclone and there was very little fouling of the scrubbers ; cleaning, in this case, would not be necessary until after 100 miles, Good charcoal obviously gives the best results, but dusty charcoal can be used with good results, except for the extra cleaning which is then necessary.

Grade 3 petrol was used for starting the engine and for driving the vehicle in and out of the garage when the fire in the producer was out.

After 539 miles' running the sparking plugs were examined, but cleaning was not necessary. The cylinder beads, induction pipes, exhaust pipes and valves were stripped down for inspection. The total weight of deposit on the cylinder heads was 168 grains, whilst the induction pipes and exhaust pipes were found to be quite clean.

The summary of the results obtained is as follows :--Total mileage, 703.1; total ton-miles, 2,827.85; charcoal used, 1 ton 4 cwt. 2 qrs. ; petrol used, 10 gallons ; average charcoal consumed per mile, 3.9 lb. ; average charcoal consumed per ton-mile, .97 lb. ; average cost of charcoal per ton-mile at £1 10s. per ton, ..156d.; saving in total running costs, including all petrol used, /2 9s. per 100 miles with petrol at 2s. 6d. per gallon ; £2 19s. with petrol at 3s. per gallon ; £3 10s. with petrol at 3s. 6d. per gallon, and £4 with petrol at 45. 'per gallon.

The trials were carried out entirely by the observer and driver appointed by the authority conducting them, after some demonstration runs and instruction during three days, and without any further .help in any way from the makers.

The air and steam preheating arrangements were adjusted for the temperature and atmospheric conditions in places like Nigeria; consequently, the full amount of water could not be used. Only .21b. of water per pound of charcoal was supplied, instead of approximately .5 lb., the result being that the gas was of a lower calorific value than

it would be in Nigeria. -Under commercial conditions the amount of petrol used for the mileage run could be reduced by more than 50 per cent.

The cylinder h,eatis examined at the completion had been untouched for 1,500 miles, representing approximately 2li00 miles' running under ordinary road conditions.

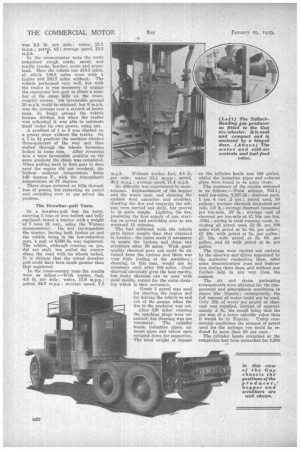

A few notes on the gas-producer employed may be of interest. In order to ensure continuous action over long distances and to maintain the gas at a high calorific value, certain mechanical features are introduced, but these are simply arranged, slow in action and of such robust design that no trouble should be experienced with them. The gas cooling and cleaning arrangements are also simple and require only a few minutes' unskilled attention daily. The charcoal hopper is carried over the driver's cab, and the fuel is fed by gravity through a mechanically operated feed valve into a furnace which is closed at the bottom by a set of

automatically rocking fire bars. A depth tube below the feed valve keeps the fire at a certain depth and porosity, however lo: the the engine may be run. The same drive which operates the feed valve and fire bars also pumps the necessary amount of water to a vaporizer. The gas from the producer passes through a cyclone dust extractor and then through a battery of coolers and scrubbers, from -which it is conveyed to the engine after being mixed with an extra supply of air which is under the control of the driver.

The working temperature of the producer is kept constant by thermostatic control of the water supply and of the admission of cold air.

The drive for the producer mechanism operates at a reduction of about 80 to 1 from engine speed. In the Guy lorry it is taken from the extended end of the camshaft by means of a worm and wormwheel in an oil-tight case, to which is attached a crank giving a 3-in, reciprocating motion. A double-acting spring buffer prevents damage to the worm gear in the event of the feed valve jamming.