2. Livestock on the move causes problems

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By P. A. C. Brockington AMIMechE

FIRST AN ADMISSION: I find it hard to criticize the lack of forward detailed planning by hauliers and builders of cattle trucks. Reason: I have visited and talked to so many recently and learned of their problems.

The comments they made to me I would say are symptomatic of the response of hauliers generally to their prospects and indicate the complexity of their problems.

The prospect of restricted driving hours overshadows plating and braking problems and the penalty of reorganizing operations to cater for the reduction of driving hours may cost four or more times the price of avoiding infringement of the plating and braking regulations.

My belief is this. In some rural areas the haulier is relying on the importance, complexity and localized nature of his job to appease Ministry examiners and police even if infringements of the weight regulations exceed the "minor" classification—given that his vehicle is in good mechanical condition.

Smaller vehicles collecting from farms for delivery to local markets or slaughterhouses are more liable to be overloaded than long-distance vehicles because of the unpredictability of the total weight of a given number of livestock. At worst only a small number of these vehicles will be grossly overloaded. There have been few convictions for overloading in the past.

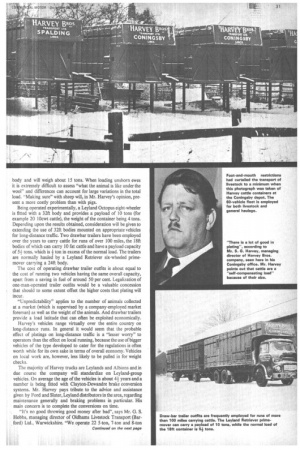

In contrast to the majority of hauliers Mr. S. G. Harvey, managing director of Harvey Bros. (Transport) Ltd., Coningsby, Lincs, considers that there is "a lot of good in plating" (although much more time should have been allowed for plating). He says hauliers will have to face up to the necessity of increasing the size of their vehicles. In his case this will include replacing a number of eighttonners with maximum-load four-wheelers and a number of fourwheelers with six-wheelers.

Mr. Harvey adds his weight to the view that reduced driving hours are, in prospect, the haulier's "biggest headache". Compensation for both developments will necessitate a rates increase of at least 100 per cent over the next three years, he says.

Mr. Harvey operates about 60 vehicles hauling livestock and agricultural produce with A-licensed vehicles but he is predominantly a livestock specialist. An average of about 60 per cent of his vehicles are used for livestock over the year. Compared with carrying livestock, general haulage will present few problems with the coming of plating.

Indeed, Mr. Harvey would welcome the plating of generalhaulage vehicles wholeheartedly if sufficient weighbridges were available for weight checking and the loader were responsible for verifying that the agreed load was placed on the vehicle, which would ensure that the correct haulage charge was made. Recently the driver of a Harvey vehicle told the dockers responsible for loading that, in his opinion, it was being overloaded. He was told: "B well take the load you're given". Returning to base, pulled in for a weight check by an MoT examiner, he was found to be carrying an overload of two tons. He ended up being prosecuted and fined heavily.

In agreement with the general view, Mr. Harvey emphasizes that plating will rarely pose a problem-when cattle only are carried because cattle are a "self-compensating" bulk load. For example, the average weight of fat cattle is lOcwt and in a typical case, 12 cattle can be loaded into a 20ft light-alloy-and-steel container carried on an 8-ton chassis (normally a Leyland Comet). The combined weight of the load and container is then only a little in excess of the rated vehicle payload. If the average weight of the beasts exceeds 10cwt, the space available is insufficient to carry the full number and a 2411 body has to be employed, based, for example, on an Albion Super Clydesdale 16-ton-gross machine providing a payload of 10.5 tons. In this case a total of 14 lOcwt cattle can be accommodated, the weight of the container being about 3 tons.

Mr. Harvey points out that a load of cattle carried on two decks is inevitably an excessive overload, the high weight of the reinforced body structure being an important contributory factor. The weight of cattle can vary by as much as +cwt each according to food intake and 12 cattle may lose 2cwt on the way to market.

Whereas the number of ex-farm pick-ups of cattle averages two/three on a rim, the number of pig pick-ups may total 18 or more. Depending on the market price of pigs quoted on the BBC early morning stock-price programme, the driver may take a small load to market or a full load to a bacon factory.

Apart from bacon pigs, which average about 2cwt, there are many other varieties weighing up to 3001b. On a 20ft body, 40 pigs on each of two decks on average weigh 8 tons and the total payload (with container) of an 8-ton vehicle is over 10 tons. It could be more, and making sure that the vehicle was not overloaded would necessitate the use of a 16-ton-gross machine.

As indicated, an 8-tonner is frequently underloaded and making sure wil therefore be extremely costly as well as being "unnecessary" *th regard to safety in the opinion of most hauliers; overloading would only be occasional as only short distances are covered with such loads. Mr. Harvey considers that the extra cost in the c e of pigs will necessitate an increase in rates of 100 per cent.

The problem of sheep is even more complex. Before shearing, 100 ewes can be carried on the two decks of a 2411 body and weigh about 10+ tons. After shearing 150 ewes can be carried in the same body and will weigh about 15 tons. When loading unshorn ewes it is extremely difficult to assess "what the animal is like under the wool" and differences can account for large variations in the total load. "Making sure" with sheep will, in Mr. Harvey's opinion, present a more costly problem than with pigs.

Being operated experimentally, a Leyland Octopus eight-wheeler is fitted with a 32ft body and provides a payload of 10 tons (for example 20 lOcwt cattle), the weight of the container being 4 tons. Depending upon the results obtained, consideration will be given to extending the use of 32ft bodies mounted on appropriate vehicles for long-distance traffic. Two drawbar trailers have been employed over the years to carry cattle for runs of over 100 miles, the 18ft bodies of which can carry 10 fat cattle and have a payload capacity of 5+ tons, which is ton in excess of the normal load. The trailers are normally hauled by a Leyland Retriever six-wheeled primemover carrying a 24ft body,

The cost of operating drawbar trailer outfits is about equal to the cost of running two vehicles having the same overall capacity, apart from a saving in fuel of around 50 per cent. Legalization of one-man-operated trailer outfits would be a valuable concession that should to some extent offset the higher costs that plating will incur.

"Unpredictability" applies to the number of animals collected at a market (which is supervised by a company-employed market foreman) as well as the weight of the animals. And drawbar trailers provide a toad latitude that can often be exploited economically.

Harvey's vehicles range virtually over the entire country on long-distance runs. In general it would seem that the probable effect of platings on long-distance traffic is a "lesser worry" to operators than the effect on local running, because the use of bigger vehicles of the type developed to cater for the regulations is often worth while for its own sake in terms of overall economy. Vehicles on local work are, however, less likely to be pulled in for weight checks.

The majority of Harvey trucks are Leylands and Albions and in due course the company will standardize on Leyland-group vehicles. On average the age of the vehicles is about 41 years and a number is being fitted with Clayton-Dewandre brake conversion systems. Mr. Harvey pays tribute to the advice and assistance given by Ford and Slater, Leyland distributors in the area, regarding maintenance generally and braking problems in particular. His main concern is to complete the conversions on time.

"It's no good throwing good money after bad", says Mr. G. S. Hobbs, managing director of Oldhams Livestock Transport (Barford) Ltd., Warwickshire. "We operate 22 5-ton, 7-ton and 8-ton Continued on the next page