at to look for in tipper chassis...

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Graham Montgomerie looks at your best specs...

r0 TRANSPORT a load quickly and at the best possible price must be the goal of every tipper operator.

And to do it he needs to make sure that he has picked the right truck for the job in the first place.

In no other sector of road miulage is this more mportant than in the :pecialised tipper field. But Nhat do you look for when ;electing your tipper :hassis?.

Well, British Leyland has )een making them longer han most so I recently anted to Jim Milloy, echnical manager (trucks) ind Arthur Lloyd (technical ;ales manager).

We went into a number of >ubjects including minimum )ower requirements, ratio ;pread and tyre sizes — points :o interest tipper operators arge and small.

For anyone fresh to the )usiness, Leyland recommends 3 six-wheeler as being the best ;ompromise of the three types lyailable.

A four-wheeler is usually )ought by companies to do a ;pecific job and an :ight-wheeler can be difficult to nanoeuvre.

If an eight-wheeler was :ssential then in cases of estricted space, a ;hort-wheelbase model might )e the answer even though it :ould be limited to 28 tons by he axle spread. The same ipplies to the short six-wheeler imited to 22 tons.

To some operators getting )n and off the site in the first >lace is the major influence in ;electing a chassis.

3ower output -Power is not the be all and he end all of a successful ipper design.'" This was the pospel according to Milloy and .loyd when we discussed iorsepower. In their opinion, in optimum figure for the iower-to-weight ratio would be lbout 7bhp/ton or 5kW/tonne you prefer. To save you vorking it out this gives around i4kW (1 12bhp) for a our-wheeler, 122kW (168bhp) or a three-axle machine and 57kW (210bhp) for a 30-ton ight-wheeler.

Enormous numbers of urbocharged engines are now ieing used because enough power can be obtained without a weight penalty. Simplifying the issue, it comes down to choosing the lightest possible engine which can give the required power.

Automatic?

The old, old story of the automatic transmission cropped up in our discussions. Both the Leyland men agreed that tipper operators are becoming more and more aware of the fact that the initial cost of a truck is less important than its total cost of ownership over its operating life. And the automatic gearbox is a case in point. Automatic means Allison, as this is really the only readily available automatic box.

The only way to justify the extra initial cost of an automatic truck to the company accountant is to find out how much cheaper the overall operating cost might be.

Although the Allison box is not offered by Leyland as an option for any of the models in the Truck and Bus range, as I

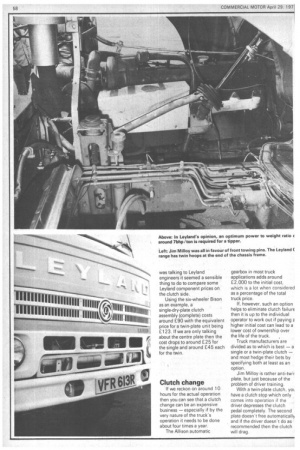

engineers it seemed a sensible thing to do to compare some Leyland component prices on the clutch side.

Using the six-wheeler Bison as an example, a single-dry-plate clutch assembly (complete) costs around £90 with the equivalent price for a twin-plate unit being £123. If we are only talking about the centre plate then the cost drops to around £25 for the single and around £45 each for the twin.

Clutch change

If we reckon on around 10 hours for the actual operation then you can see that a clutch change can be an expensive business — especially if by the very nature of the truck's operation it needs to be done about four times a year.

The Allison automatic

gearbox in most truck applications adds around £2,000 to the initial cost, which is a lot when considered as a percentage-of the total truck price.

If, however, such an option helps to eliminate clutch failure then it is up to the individual operator to work out if paying t higher initial cost can lead to a lower cost of ownership over the life of the truck.

Truck manufacturers are divided as to which is best — a single or a twin-plate clutch — and most hedge their bets by specifying both at least as an option.

Jim Milioy is rather anti-twir plate, but just because of the problem of driver training.

With a twin-plate clutch, yoi. have a clutch stop which only comes into operation if the driver depresses the'clutch pedal completely_ The second plate doesn't free automatically and if the driver doesn't do as recommended then the clutch will drag.

As far as the actual ratios are ;oncerned, Jim Milloy was 3mphatic that the gearbox ;hould have a crawler gear — )rat least the ability to crawl )ut of trouble in soft going. 3uch a low ratio is also very ..iseful if the driver is required o spread the load as he is ipping it.

Both the Leyland men ;uggested a figure of 70 to 1 or the overall transmission eduction, but Arthur Lloyd ;ommented that several )perators preferred to make do vith a 50 to 1 reduction. As an xample to illustrate how the werall reduction works, the _12:engined Leyland Octopus as top and bottom ratios of ).75 and 7.17 to 1 espectively in its six-speed :onstant-mesh box which gives first reduction of 9.56.

Selecting the 7.712 axle ratio from the list of options thus gives an overall reduction pf 73.7, which thus easily meets Jim Milloy's recommendations.

Overdrive

This six-speed box can also be used to illustrate the point

that it is a good idea to have an overdrive ratio to save the engine being flogged as 99 per cent of all tippers come back unladen. But, as I mentioned, the tipper man also needs the ability to crawl along at 2mph so you can see where the 70 to 1 reduction comes in, To quote Jim Milloy: This is the starting line for a tipper specification. With modern road networks everyone is within easy reach of a motorway, but the tipper has to be able to get out of bad

ground with the driver's foot nowhere near the clutch and you need a good ratio spread to be able to do this.' '

Coming now to the rear axle(s) it was agreed that as far as Leyland is concerned there is no way that a 7 to 1 reduction can be achieved with a single reduction axle — some form of double reduction is essential. How this is achieved is again open to argument, but the weight of Leyland opinion comes down in favour of hub reduction for tippers. Hub reduction cuts down the stress in the half-shafts, but it means that the differential operates at

a higher speed so that correct • design is essential.

All manufacturers tend to build a standard haulage frame and then flitch it for tipper operation. The method of assembly varies from factory to factory, but Leyland never uses rivets, considering that bolted frames are better.

On the Continent, the standard frame width is around 31 inches whereas the 34 inch frame is favoured in the UK. Both Arthur Lloyd and Jim Milloy though that Britain might have to go for the 'narrower frame to fall in line with Europe.

As Jim Milloy said: "The front end of a tipper tends to be standard and so does the rear. What isn't standard is the dimension in between." And as far as wheelbase is concerned most UK operators go for the shortest legal wheelbase they can get their hands on.

Suspension

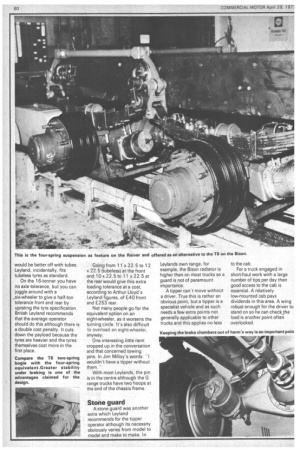

For the suspension on the rear bogie for six and eight-wheelers, Leyland recommends a two-spring design as being better all round, especially in the areas of adhesion and braking. In the past, the four-spring bogie_has _ tended to be lighter, but the Leyland T6 two-spring design, which makes great use of pressings to keep the weight down, is claimed to be about the same.

One of the reasons for the move to the two-spring bogie was that there is a saving in the number of bits and pieces including bushes, pins, etc.

Many operators go for automatic chassis lubrication and Jim Milloy was really in two minds over its viability. "I'm against it for oil spillage, but as an engineer I'm for it. I do feel, however, that with modern day metallurgy and materials we should be trying to eliminate lubrication entirely."

Tyre specs

With a 16-tonner, the choice is usually with 10.00 x 20 tubed or 11.00 x 22.5 tubeless. It is really a matter of how rough the operation is. On good roads, tubeless tyres would be the best bet, but for really rough stuff the operator would be better off with tubes. Leyland, incidentally, fits tubeless tyres as standard.

On the 1 6-tonner you have no axle tolerance, but you can juggle around with a ,six-wheeler to give a half-ton tolerance front and rear by uprating the tyre specification. British Leyland recommends that the average operator should do this although there is a double cost penalty. It cuts down the payload because the tyres are heavier and the tyres themselves cost more in the first place. Going from 11 x 22.5 to 12 x 22.5 (tubeless) at the front and 10 x 22,5 to 11 x 22.5 at the rear would give this extra loading tolerance at a cost, according to Arthur Lloyd's Leyland figures, of £40 front and £253 rear.

Not many people go for the equivalent option on an eight-wheeler, as it worsens the turning circle. It's also difficult to overload an eight-wheeler, anyway.

One interesting little item cropped up in the conversation and that concerned towing pins. In Jim Milloy's words: "I wouldn't have a tipper without them."

With most Leylands, the pin is in the centre although the G range trucks have two hoops at the end of the chassis frame.

Stone guard

A stone guard was another extra which Leyland recommends for the tipper operator although its necessity obviously varies from model to model and make to make. In Leylands own range, for example, the Bison radiator is higher than on most trucks so a guard is not of paramount importance.

A tipper can't move without a driver. True this is rather an obvious point, but a tipper is a specialist vehicle and as such needs a few extra points not generally applicable to other trucks and this applies no less to the cab.

For a truck engaged in short-haul work with a large number of tips per day then good access to the cab is essential. A relatively low-mounted cab pays dividends in this area. A wing robust enough for the driver to stand on so he can check the load is another point often overlooked.