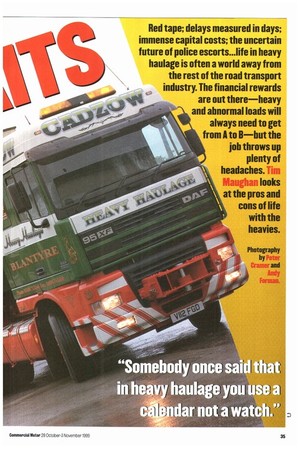

Red tape; delays measured in days; immense capital costs; the

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

uncertain future of police escorts...life in heavy haulage is often a world away from the rest of the road transport industry. The financial rewards are out there—heavy and abnormal loads will always need to get from A to B—but the job throws up plenty of

headaches. Tim Maughan looks

at the pros and cons of life with the heavies.

Photography by

D he haulage industry contains many diverse sectors, but there can be few as specialised as heavy haulage. A host of factors pose special obstacles for the operator, though ironically these can also serve to protect a business from unwanted competition.

The complexities of life as a heavy haulier become apparent when CM pays a visit to Lanarkshirebased Cadzow Heavy Haulage, based a few miles from Glasgow. Even before we are safely ensconced in the office of director John Gardiner, it's obvious that this is not your average haulier. The tractive units are visibly larger, complete with ballast to compensate for hauling loads of up to zoo tonnes. These vehicles do not come cheap: expect to pay at least £150,000 for a new artic capable of carrying heavy or abnormal loads.

Cadzow was founded in 1973 by Jim McCauley, the present managing director. Gardiner joined

in 1978, "when the company had three low-loaders and three trailers. They were used to shift local plant machinery around the Glasgow area," he says. "Then we started to carry heavy engineering equipment around the UK—consignments varied from pressure vessels up to 70-tonne locomotives. We had a varied customer base from day one."

It has been a tale of steady growth. The firm now runs II tractors and 28 trailers, including low-loaders and extendibles. Last year it invested in state-of-the-art modular equipment in the form of a £300,000 Goldhofer trailer which can extend from 15m to 32.m and is thought to be the largest commercially used trailer in Scotland. "It is a long-term investment," says Gardiner.

In addition to heavy haulage, vehicles such as excavators operate under the banner of Cadzow Plant Hire: they are used chiefly in local construction. But 70% of Cadzow's investment is ploughed into the heavy brigade. Transporting hefty equipment can mean generators or tanks, but the most common load is machinery used in the construction industry, whether it be in the manufacturing, service or housing sectors. Diggers and cranes need moving, and, as McCauley says, this means a building boom is inextricably linked with work for the heavy haulier—but building slumps can be devastating.

"The construction industry is busy at the moment in the Glasgow area, because of the low interest rate," says McCauley. Work there is, but on a national level the real boom is happening elsewhere. "Scottish manufacturing is at a disadvantage," he adds. "Most of the work is going on in England, and Government policy means there is no work in road building."

The bulk of the company's work is split 50-50 between England and Scotland, but it also operates in the Irish Republic.

Strategic considerations

Geography is a factor in this sector, but there are other important strategic considerations. For example, 20% of Cadzow Heavy Haulage work is contracted out. Flexibility is crucial in an industry characterised by such massive capital investment—a haulier can more often than not afford a 7.5-tonner to lie idle for a bit, but it's a different story when you're looking at a piece of machinery priced in six figures.

Then there are day-to-day factors. By law, any vehicle over 3.5m wide or 18.3m long requires a driver and an assistant (in practice often a steersman). This immediately doubles the wage bill. Also, these fuel-thirsty vehicles do a maximum of around smpg. Because heavy haulage vehicles rarely exceed 40mph, trips are long drawn-out affairs; and all the time fuel is being consumed and men have to be paid.

Gardiner says: "Somebody once said that in heavy haulage you use a calendar not a watch." And McCauley adds: "We keep a strict maintenance regime. We have to change trailer configurations—you cannot do without fitters in this sector of the industry."

Such overheads are costly, and are an inescapable part of the job. Yet rates do not always reflect such expenses. "There is not a true return for the amount of capital invested," McCauley believes.

CM heads south to visit heavy haulier Hallett Silbermann in Hatfield. Like Cadzow Hallett Silbermann maintains a plant arm—Metroplant. The 50-strong fleet is in two distinct sections: general haulage accounts for 6o% of business and heavy haulage takes the rest. The two are also geo

graphically split in a graphic example of Jim McCauley's view that, in terms of work, the South-East is where it's at for the heavy haulier Managing director David Silberrnann says: The lifting capability is split between our depots in Birmingham and Hatfield. The West Midlands is more machine-tool orientated, whereas the South-East is more construction; therefore we operate our low-loaders from Hatfield." Reflecting the different markets, rigids with lorry-mounted cranes largely operate from Birmingham.

Silbermann adds: "There is a tremendous amount of construction going on in London. Our low-loaders go into Central London four or five times a week" He explains that no less than 5o% of the firm's business is derived from work "within the M25".

The firm's heavy haulage capability is in demand but, as with Cadzow north of the border, this work brings extra running costs. Hallett Silbermann sales director Jon Hugill says: "Drivers involved in heavy haulage do get paid a higher rate because of their necessary skills." He adds that such staff command a higher wage than typical Class i drivers. They have to drive the vehicle and know exactly how to load and unload consignments correctly. "No two jobs are the same and the driver has to be experienced," says Hugill. Such experience comes with time, and the firm wants to keep its seasoned drivers, To this end a loyalty scheme is in place; at Christmas drivers receive a lump sum which increases with each year of service.

Contentious issue

Wages are an important topic, but the most contentious issue affecting heavy haulage is the future of police escorts: and here the industry is divided. Operators in the heavy haulage sector must, bylaw, inform the police before embarking on a journey (see guide), Last November the Home Office produced a consultation document proposing that motorway escorting should be privatised. The document has yet to be published, and a Home Office spokesman told CM that no date had been set for this. But for operators like Hallett Silbennann something has to change.

Under the present system, once the customer has given details of the journey, the haulier must contact the police, as well as the highway authorities whose territories will be entered. As there is no centralised body overseeing the trip, the onus is on the haulier to inform every party. For a journey from, say, Newcastle to Brighton, this is an administrative nightmare. The haulier must con tact every single police force and highway authority, and different weights and dimensions mean various notice periods.

It can be exhausting work, made all the more frustrating because the authorities are

not obliged to acknowledge the haulier's travel notice. The operator must assume that his fax has got through, and that the allimportant police escort will be on the county border on the day.

But with a Special Order the Department of Transport has the power to stop a heavy load from moving. These sanctions are "few and far between', according to Hugill, but it does indicate the red tape that can tie a heavy haulier in knots.

The current system can present the operator with mammoth problems as Jim McCauley explains: "We often get stranded.

A driver can sometimes be stuck for up to five hours, and this could be in just one

county. We favour night work because it is

quieter, but during these hours the police often refuse to escort us." And in the event of an emergency elsewhere the police escort departs—leaving the heavy haulage vehicle stranded again.

McCauley estimates that 50% of journeys are delayed by police escorts arriving late.

This situation certainly needs to be streamlined, but Cadzow's managing director believes that such escorts must remain a police responsibility. John Gardiner agrees: "Members of the public slow down for a blue light—but not an orange light."

Financial dimension

John Atkinson, owner of Betchworth International Heavy Transport, based near Reigate, Surrey, would also like to see the police continue to provide escorts, but at a price. Such a financial dimension would give the haulier more power as a paying customer, he believes. Atkinson adds: "I would like to see the police escorts continue but I don't think they will."

If privatisation were introduced, he would like to see a multitlide of escort firms operating across the UK, rather than one powerful monopoly. Atkinson foresees a situation where private firms will provide motorway escorts, leaving the police to cater for escorts on local roads.

Tim Culpin, treasurer of the Heavy Transport Association and a solicitor specialising in transport law at Aaron ec Partners in Chester, says there is a problem when heavy hauliers notify the powersthat•be; police forces are generally quite good at acknowledging faxes but that is not true of the highway agencies. He points Out: "The fact is that hauliers very often do not have the choice if they are escorted or not. The cowboys don't bother with the paperwork—they just move."

This kind of unauthorised movement can be horribly dangerous. The role of the

authorities is to plot a safe route through a given county. Flouting the rules could lead to incidents such as bridge bashing, warns Culpin. He would like to see a centralised body dealing with heavy haulage movements throughout the country, but admits that without Government investment this would be difficult to achieve.

Control room

How do the police themselves see their role in all this? The Association of Chief Police Officers (AC PO) is in favour of privatising escorts, but what about the copper at the sharp end? Sgt Dave Hasney, duty officer at the control room of North Yorkshire Police, highlights the complexities of the job. Although North Yorkshire's business is chiefly in agriculture, the location—with Scotland and the heavily industrialised areas of Tyneside and Teesside to the north and West Yorkshire to the south—means that heavy loads frequently pass along its roads. And North Yorkshire is a very big county. "We are a rural county and we are thinly staffed," Hasney points out He describes how the escort system works. "We receive the faxes, and if there is no problem the haulier does not hear from us. We only reply if we are too busy to provide an escort."

Two cars, each manned by one police officer, are typically deployed to escort, says Hasney. "It is time escorts were privatised," he adds. "The police have done the job for many years and it is second nature. But we have limited resources, and the sheer size of the vehicles mean that they cannot just be left."

It seems that the police at all levels are in favour of escorts being privatised. Significantly, other sectors of haulage do not attract such attention from the police. Yet again, this highlights the unique nature of heavy haulage. That difference shows itself in the bureaucracy, the lengthy delays, and the massive overheads. Yet, done properly, it is lucrative work: the occupational hazards can be outweighed by net profit. The hassles of the job are certainly there, and the same hassles also make entering the sector—and staying in it—a risky business. Only those willing to invest and do the job thoroughly can hope to thrive.

David Silbermann concludes. "Some cut the corners and break all the rules— and that is the sort of competition we can do without. It is not a two-minute operation and it needs a lot of planning. People who do come into heavy haulage often become unstuck. It is a business where you need to have a lot of patience. But if you have this and follow the procedures it has its rewards."

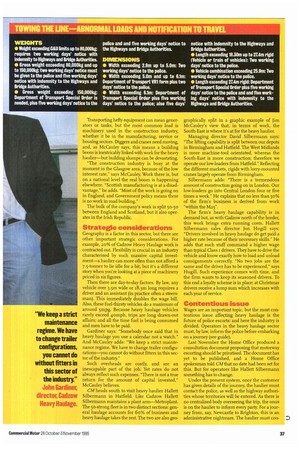

TOWING THE UNE ABNORMAL LOADS AND NOTIFICATION TO TRAVEL

WEIGHTS

• Weight exceeding C&U limits up to 80,0004: requires two working days' notice with indemnity to Highways and Bridge Authorities.

• Gross weight exceeding 80,000kg and up to 150,000kg: two working days' notice must be given to the police and five working days' notice with indemnity to the Highways and Bridge Authorities.

• Gross weight exceeding 150,000kg: Department of Transport Special Order is needed, plus five working days' notice to the police and and five working days' notice to the Highways and Bridge Authorities.

DIMENSIONS

• Width exceeding 2.9m up to 5.0m; Two working days' notice to the police.

• Width exceeding 5.0m and up to 61m: Department of Transport VR1 form plus two days' notice to the police.

• Width exceeding 61m: Department of Transport Special Order plus five working days' notice to the police; also five days' notice with indemnity to the Highways and Bridge Authorities.

• Length exceeding 18.30m up to 214m rigid (Vehicle or train of vehicles): Two working days' notice to the police.

• Vehicle combination exceeding 25.9m: Two working days' notice to the police.

0 Length exceeding 27.4m rigid: Department of Transport Special Order plus five working days' notice to the police and and five working days' notice with indemnity to the Highways and Bridge Authorities.