A Good Start for

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

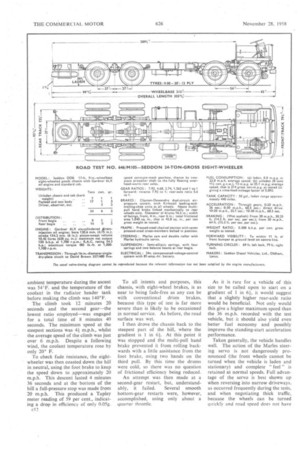

I New Range New Seddon Eight-wheeler Tested with Gardner 6LX 150 b.h.p. Oil Engine. Reveals Good Overall Economy. Eight-wheel Brakes Give Constant Safety By. John F. Moon, A.M.I.R.T.E. THE announcement last August that Seddon Diesel Vehicles, Ltd., Oldham, were to manufacture maximum-capacity sixand eightwheelers was received with great interest by operators of heavy vehicles, for this concern has established a reputation for high-quality vehicles at competitive prices. One of the power units offered in the new range is the recently introduced Gardner 6LX 150 b.h.p. oil engine, and the first road test of one of the new Seddons was combined with the first road test of this new unit.

It showed the vehicle to be highly successful as an initial venture into this field, and the order book for models in the new range is reported to be rapidly filling.

High-quality Engine

The 6LX engine has the fueleconomy advantages of the less powerful 6LW, which, before the introduction of the 6LX, was the most powerful Gardner engine suitable for use in eight-wheelers, whilst the extra power should enable faster operating schedules to be .maintained. The Gardner tradition of high-quality workmanship, reduced maintenance and overall longevity will apply as much to the 6LX as to the earlier units.

Fully described in the August 22 issue of The Commercial Motor, the DD8 eight-wheeler tested is one of a range of eight models. The•particular chassis which! handled is now in service with Cyprien-Fox,• Ltd., London; N.7, and has been fitted with a dropsided body.

As is usual with Seddon" designs, simplicity is the keynote, but there is a wide choice of power units, transmissions and axle layouts.

Three Eight-wheelers

So far as the eight-wheelers are concerned, there are two 17-ft. 9-in.-wheelbase models—the DD8 with a doubledrive bogie and the SOS with a single driving axle—and there is a 14-ft. 6-in.-wheelbase version with doublet drive bogie for tipper use. Other models include singleand doubledrive six-wheelers and twin-steer sixwheelers.

The kerb weight of the chassis and cab as tested was 7 tons 11 cwt. and the imposed load consisted of a wellreinforced test body, and steel and concrete weights, these adding up to

17 tons If cwt. With myself and Frank Galbraith, of Seddon, aboard, the DD8 had a gross weight of 24 tons 61 cwt.

Allowing half a ton for a light-alloy platform body, the chassis should, subject to the chassis specification chosen, be suitable for a payload of some 161 tons without exceeding the maximum legal limit of 24 tons.

c10

Optional equipment fitted to the test vehicle which Would add slightly to the unladen weight included brakes on the second axle and Marles powerassisted steering. These two items can in no way be considered superfluous, for the extra braking area Was shown to give decided advantages in respect of maximum retardationand almost complete absence of fade, whilst the power steering, although not essential on the open road, is of inestimable value when manoeuvring in confined spaces.

It was unfortunate that the roads were still wet when the braking tests were conducted, rain having fallen continually during the morning, although it had stopped by the time the tests were made. The figures obtained, however, suggested that on a completely dry road surface the stopping distance from 30 m.p.h. would have been reduced by some 10 ft. or so. Even so, the figures recorded on a wet road were some 25 per cent. better than can be expected on a dry road with a six-wheel-braked eight-wheeler, further emphasizing the advantages of. eight-wheel brakes.

All stops were made without any loss of stability or control. Indeed, the only effect that the wet surface seemed to have was to allow the rear bogie wheels to lock slightly, a distance of 25 ft. being measured from 30 m.p.h. out of a total stopping distance of 64 ft.

• Comparison between the average retardation as shown by the stopping distance and the maximum retardation as recorded by the Tapley meter• indicated that skidding was accounting for a reduction of about 17 per tent. efficiency, although some of this could be attributed to a slight delay in the air-pressure build-up.

Acceleration tests along a wide level stretch of road in the Chadderton area (used also for braking) showed that the Gardner 6LX could give reasonable performance despite its low governed maximum speed and hence limited speed range. The ratios of the David Brown 557/480 five-speed gearbox have been chosen specifically to suit the torque characteristics of the 6LX and therefore their spread is well suited to the speed range of the engine.

Direct-drive acceleration tests emphasized the smoothness of the transmission and the good low-speed torque of the 6LX. The •figures obtained are again reasonable •for an engine of this type, pulling a relatively high rear-axle ratio. The impression of good top-gear performance was confirmed throughout the test and was one of the most marked improvements of the new unit over the smaller 6LW.

Fuel-consumption tests were conducted over a distance of 16 miles. The circuit was traversed in two stages, because the fuel test tank used had a capacity of only a gallon. The route was slightly undulating and seven sets of traffic lights had to be negotiated on each leg of the run, thus the amount of indirect-gear work necessary was about equivalent to that needed on a normal trunk run in Great Britain.

The gradient was more favourable on the return run than on the outward journey, with the result that 9.6 m.p.g. was obtained in one direction, cornpared with 8.3 m.p.g. in the opposite direction. The fuel-consumption rate for the complete test worked out at 8.8 m.p.g., the overall average speed being 23.8 m.p.h. This result suggests that a clear 9 m.p.g. would be obtained on a good main-road trunk run.

This same course was retraced on the second day of the test with the weights removed but with the test body still attached. The gross running weight was reduced to 8 tons 11+ cwt., but remained greater than would be the case with a normal body. On this occasion, the variation in gradient was found not to affect the fuel-consumption rate, both legs being completed at an average rate of 13 m.p.g. and at an average speed of 25.1 m.p.h.

Operators engaged on normal giveand-take service who are obliged to run their vehicles for half the time without a load can expect to obtain a clear 11 m.p.g. overall average from the Seddon •eight-wheeler with 6LX engine.

For the hill-climbing tests, the DD8 was taken up Buckstones Road, Shaw, which is a 11-mile slope having an average gradient of 1 in 12. The ambient temperature during the ascent was 54°F. and the temperature of the coolant in the radiator header tank before making the climb was 140°F.

The climb took 12 minutes 20 seconds and the second gear—the lowest ratio employed—was engaged for a total time of 8 minutes 40 seconds. The minimum speed at the steepest sections was 41 m.p.h., whilst the average speed of the climb was just over 6 m.p.h. Despite a following wind, the coolant temperature rose by only 20° F.

To check fade resistance, the eightwheeler was then coasted down the hill in neutral, using the foot brake to keep the speed down to approximately 20 m.p.h. This descent lasted 4 minutes 36 seconds and at the bottom of the hill a full-pressure stop was made from 20 m.p.h. This produced a Tapley meter reading of 59 per cent., indicating a drop in efficiency of only 0.05g.

c12 To all intents and purposes, this chassis, with eight-wheel brakes, is as near to being fade-free as any can be with conventional drum brakes, because this type of test is far more severe than is likely to be occasioned in normal service. As before, the road surface was wet.

I then drove the chassis back to the steepest part of the hill, where the gradient is 1 in 61. At this point it was stopped and the multi-pull hand brake prevented it from rolling backwards with a little assistance from the foot brake, using two hands on the third pull. By this time the drums were cold, so there was no question of frictional efficiency being reduced.

An attempt was then made at a second-gear restart, but, understandably, it failed. Several smooth bottom-gear restarts were, however, accomplished, using only about a quarter throttle. As it is rare for a vehicle of this size to be called upon to start on a gradient of 1 in 64, it would suggest that a slightly higher rear-axle ratio would be beneficial. Not only would this give a higher maximum speed than the 36 m.p.h. recorded with the test vehicle, but it should also yield even better fuel economy and possibly improve the standing-start acceleration performance.

Taken generally, the vehicle handles well. The action of the Manes steering servo is not dangerously pronounced (the front wheels cannot be turned when the vehicle is laden and stationary) and complete " feel" is retained at normal speeds. Full advantage of the servo is best shown up When reversing into narrow driveways, as occurred frequently during the tests, and when negotiating thick traffic, because the wheels can be turned quickly and road speed does not have to be greatly reduced when pulling out to pass obstructions.

During the fade test down Buckstone Road, the engine was stopped to judge the steering characteristics without the servo, and I found that at 20 m.p.h. it was by no means heavy. If the servo failed when on the move, the driver should still be able to control the vehicle without any drastic increase in physical effort.

The gear-change action of the David Brown gearbox is first-rate and effort is further reduced by low clutch-pedal .pressure. It is possible to make fast changes upwards without double

declutching, particularly between second and third gears, but the more usual technique necessitates pauses between changes because of the time taken for the speed of • the Gardner engine to die down when the throttle is released.

Plastics Cowl The engine cowl is a single-thickness plastics moulding which did little to conceal noise, but it was possible to talk at little above the normal volume. A certain amount of heat penetrates into the cab, 'particularly through the lower right-hand cowl panel, which is adjacent to the exhaust manifold.

The excellence of the brakes in emergencies has already been noted, but they are of a high standard also under normal conditions, the use of a conventional long-travel pedal giving the driver fully progressive action. The driving position is good and the seat is adjustable vertically and longitudinally. All-round visibility is splendid.

A good finish has been achieved in the timber-framed, plastics-panelled cab; polished timber fillets and woodgrain-finish plastics trim panels give an air of luxury. There is plenty of room on both sides of the engine cowl and acaess to the seats from ground level is aided by the wide hub step rings.

Effective Demister Standard cab fittings include a heater and demisting unit (which proved effective during the heavy rain that fell throughout much of the test); an interior light; two ashtrays; flashing direction indicators; and twin windscreen wipers driven off a single internally mounted electric motor.

Maintenance tests revealed a normal standard of accessibility for a vehicle of this type and the standard tool kit , was employed throughout. My first task was to verify the water level and this took 6 seconds, following which I attempted to check the engine-oil level by using the small trap at the rear of the left-hand side panel.

Unfortunately, the position of the mate's seat brackets made it impossible

to open the trap far enough to withdraw the dipstick, so the main panel had to be removed, the complete check taking 69 seconds. This is to be solved by locating the dipstick. nearer the front of the engine in future applications.

Checking the gearbox-oil level proved to be a little awkward, because of the difficulty of reaching the combined filler and level plug from below, but I managed to complete this task in 24 minutes.

Each rear axle has a wide filler mouth closed by a flat plate secured by two nuts. It is necessary only to slacken these nuts, when each plate can be swung aside, and in this way I was able to check each rear-axle level in 11 minutes.

The fluid reservoir for the clutchoperating system is carried on the right of the engine cowl and its level can be ascertained in 19 seconds. The large Oil-bath air cleaner is located beneath the cab floor, ahead of the near-side front wheel, as is usual with Seddon heavy vehicles, and the bowl and filter element assembly is held to the main body by a clamp ring and two large wing nuts. The level of the oil in the filter took 2 minutes 5 seconds to check, Checking Battery There are two 12-v. batteries in a crate on the left of the chassis frame. These are protected by a plastics cover secured by angle-iron framework. By hingin4 the framework upwards and sliding the cover outwards it was possible to check the level of the electrolyte in the cells in 3+ minutes.

This done, I adjusted the brakes on each of the front axles in I minute 50 seconds, and an each of therear axles in 3+ minutes. All eight brakes can be adjusted in under 12 minutes. While doing these jobs I used the standard hydraulic jack provided in the tool kit, placing it centrally beneath each axle to raise both wheels simultaneously.

The spare wheel is held by two selflacking nuts underneath its carrier, which makes it necessary to lie down beneath the vehicle to remove them. Additionally, the wheel is located by two dowels, which tend to create difficulty in sliding it in and out.

Nevertheless, single handed I removed the wheel in 24 minutes and restowed it in 2 minutes 50 seconds.

Next I withdrew and replaced the element of the primary fuel filter in 14 minutes. The filter is on the left chassis side member, immediately ahead of the fuel tank.

Detaching Panels I then turned my attention to the engine which is accessible by removing the three-piece cowl. The left side section is secured by three spring clips and the right section by two clips, and 1 detached the two panels in 19 seconds and 17 seconds respectively.

The upper section, which includes a hinged panel to give access to the engine oil filler, was then lifted off its two locating dowels in 17 seconds. Originally the vehicle had a four-piece steel cowl which was extremely difficult to remove, but the normal Seddon practice of using plastics panels has greatly improved the position.

-This done, I withdrew and replaced the element of the main fuel filter in 51 s'econds. Time did not permit me to remove an injector, although Gardner's assure me that injectors on the 6LX are easier to remove than on the LW series of engines, presumably if the correct tools are available.

Replacement of the engine cowl sections was reasonably easy. The upper moulding was returned in 17 seconds, and each of the two side panels in 36 seconds, slight difficulty being experienced in locating the lower edges of these panels over their securing hooks.