)cal Delivery

Page 43

Page 42

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

CARRYING a 1-ton payload and making four stops to every mile, the Trojan oil-engined van operates at a lower fuel cost than many If-litre private cars used for ferrying their owners from the suburbs to the cities. This was shown during a comprehensive test of the van, when a fuel return of 27i m.p.g. was obtained on a localdelivery trial. With normal running, the consumption rate was almost 40 m.p.g.

In comparison with the petrol-engined Trojan, which is known for its economy, the oil-engined version covers 50 per cent. more ground on a gallon of fuel while carrying one-third more load, and is quicker off the mark. The trials indicate that where the 15-cwt. petrol-engined van is giving a fuel return of 24 m.p.g., the oiler, with equal payload, would afford a consumption rate of about 45 m.p.g.

As a normal-control chassis, with a fairly high axle ratio, the Trojan is more generally used for point-to-point shortdistance work totalling 400-500 miles per week, than for house-to-house delivery. Assuming that the Perkins threecylindered unit is as low in its maintenance cost as the Trojan engine, and that oil fuel is approximately the same price as petrol, there should be a saving of about £2 I0s. per week on this type of work. In this country the difference in fuel cost is 44-d. per gallon. The difference in first cost of the two vans, including purchase tax is £256, which might be recovered in the first two years' operation of the oiler.

a8 In fitting the Perkins engine a few body modifications have been requireC to the standard model because of th greater length of the compression ignition unit, and detailed alteration. have been made to increase payload, There are now two body styles available for the 1-tonner, the former pattern, 6 ft. 3 ins. long, being supplel mented by a standard body which il approximately 8 ins. longer. Th9 bonnet is lengthened and the body IS mounted 2 ins, to the rear of tlt normal position. In chassis and cab form there is 7 ft. of platform space for special types of bodywork.

Special mountings are employed for the engine, two sandwich units in compression being fitted above the crankshaft at the front and there is a. dual rubliierbonded unit in shear on each side of the fg clutch housing. Snubbers are arran ed at the sides of the gearbox. Because the respective outputs of the petrol and oil engines are similar, the transmission system remains unchanged, but the gearbox case has a new casting shaped for the Perkins engine.

This is a three-cylindered version of the Perkins standard range, with a spe iaI deep-well sump shaped to provide el arance at the axle. Provision is made for a fan if required. Special measures have been taken in balancing the crankshaft and all the engines are checked for smooth operation on a special bench rig at the Trojan works. After extensive tests a standard has been set for limits of

vibration throughout the governed

speed range, and all production units are adjusted to within this range.

There has been no change in gear or axle ratios, because the power curves of the Trojan and Perkins engines. are somewhat alike, but a slight modification has been made to the intermediate-gear tooth form to improve locking of the synchronizing gear. The hypoid final drive and Lockheed hydraulic braking system are recent developments in the standard Trojan chaSsis, but rear

springs similar to those used in battery electrics, heavier-section wheels and truck-type tyres have been incorporated in the oil-engined version because of the uprated payload. An 11-plate battery is standard for the oil-engined van.

Although the Trojan oiler is approximately 2 cwt. heavier than the petrol version, it is still within the 25-cwt. class for taxation purposes. Complete with full tank, spare wheel, tools, additional fuel in cans and accessory test equipment, the van weighed 1 ton 7-1 cwt. unladen on the first trip to the weighbridge.

One ton of castings formed the kayload, and the auxiliary fuel tank was filled in readiness for a full day's work. As it was a moderately warm day, with an ambient temperature of 57 degrees F., about a third of the effective area of the radiator was blanked off and the test was started from cold. The engine, which was installed without a fan, fired without the use of the cold-starting equipment and the van was headed towards Succotnbs Hill.

Within a few hundred yards of the works, the Trojan was climbing the 1-in-30 incline past the airport, gaining speed all the time. Soon afterwards it was tackling the Succombs gradients from a moving start, climbing the 1-in-5 ..section at the foot in low gear. As the incline slackened to 1 in 10, the engine surged to governed speed and second gear was engaged, and the vehicle kept pulling happily.

1 watched the radiator top-tank temperature rise as the test continued, but it was well below boiling point after climbing the 1-in-4 section in low gear. This was encouraging, because earlier attempts with the petrol-engined van had met with failure. Without loss of time a second attempt was made from a standing start, again without any sign of falling-off from governed speed. By this time the water temperature had risen to 185 degrees F.

I then ventured a third climb, with stops at the most difficult points. The van started from rest on 1 in 6 and again on 1 in 5, but on the steeper section had little power in reserve. it met its Waterloo in a restart test near the top of the hill, where the road bends, and the Tapley meter regikered 1 in 4.1-. After unsuccessful attempts to start from rest on this section, the Trojan was reversed to a more favourable point and then completed the climb. By this time the water was nearly boiling, but a fourth

climb from the foot of the hill failed to make the temperature rise above 208 degrees F.

For good measure, the vehicle was driven up Bug Hill nearby, which, although requiring low gear, was a comparatively slight obstacle. The test tank was topped up with five pints of fuel, equal to a consumption rate of 21 m.p.g.' which, considering the amount of indirect-gear work, was reasonably economical.

Before making further tests the speedometer and mileometer were checked and results throughout the day were compensated for inaccuracies in the instruments. The first non-stop consumption test, staged over an out-and-return course between Westerham and Sevenoaks, was reasonably level, but with a half-mile second-gear climb near the turning point. Keeping the maximum speed to a nominal 30-35 m.p.h., corresponding to 1,600-1,900 r.p.m. engine speed, a fuelconsumption rate of 38.6 m.p.g. was returned.

A four-stop-per-mile test followed, in which the engine was idling during each 15-sec. stop. At first the rapid acceleration misled me in my judgment of 440 yds. between stopping points, but after the first mile I allowed about 45 secs. running time between stops and adjusted the time to the correct average before finishing the trial.

It was during the numerous stops that I noted the effects of the engine suspension. There was oscillation on the gear lever, which is part of the engine-gearbox unit, but no perceptible movement on the driving mirror, DI 0 wings or other outrigged components. With my hand resting on the lever during acceleration, I observed oscillation periods, but, again, they were not transmitted to the frame. I Had the gear lever been remotely mounted and the engine cackle effectively silenced, it would have been difficult to detect that there was a three-cylinderedloil engine below the bonnet. A noiseabsorbent panel; is incorporated in the scuttle and an oil-bath air cleaner is fitted to the engine.

As an indication of the rapid acceleration, the course was completed at an average running speed of, 20.5 m.p.h. The consumption rate of 27.4 m.p.g. obtained under these conditions is unusually economical for a vehicle hatiling a 1-ton payload on local delivery. The vehicle is well suited for such work, both in transmission and body design, the normal-control cab having large doors and full-drop windows. When climbing Titsey Hill, noted for its length and gradient, the water temperature rose from 170 degrees F., the normal running level, to 185 degrees F. at the end of the climb. A reasonably level stretch was found near Warlingham for the short performance trials, in which the first emergency brake application caused a rapid change in the distribution of the payload. When I put my foot hard down on the brake pedal the wheels appeared to take root in the road and the castings, fuel cans and other gear crashed up against the two seats.

No damage was done to personnel or the vehicle, but as repeat tests were to be made, the load was not redistributed until after the brake tests were completed. There was nothing lacking in retardation, stopping distances of 22 ft. from 20 m.p.h. and 48 ft. from 30 m.p.h. being obtained with only slightly more pedal pressure than normal.

The Trojan has a three-speed gearbox which I found Was well spaced in its gearing for the power-weight ratio provided by the oil engine. This was shown during the acceleration trials, when it took 17.5 secs, to reach 30 m.p.h. from a standing start. In all respects the vehicle is nicely geared for its work and load because, in addition to affording smooth acceleration from 20 m.p.h., it has a maximum speed of 43-44 m.p.h. in top gear. From 10 m.p.h. the acceleration in direct drive was reasonable, but was accompanied at the lower speeds by oscillation of the gear lever. Nevertheless, the time of 18.7 secs. to reach 30 m.p.h. from a rolling start is sufficient to indicate that the axle ratio is right for the load and the torque.

Up to this point the Trojan had been working hard,

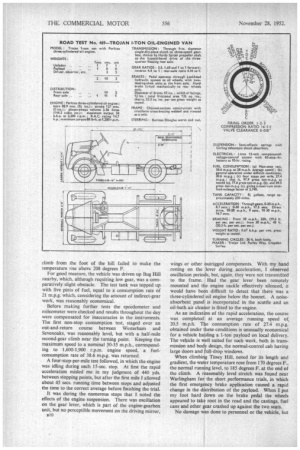

(Left) The Perkins three-cylindered oil engine is mounted low in the chassis, and for normal operation is installed without a fan. As shown here, an auxiliary test tank was fitted below the bonnet for the fuel.

consumption trials and an ether tube thermometer was incorporated in the radiator top tank. An oil bath air-cleaner is standard.

climbing and reclimhing hills and making many stops, and apart from the continuousrun test, there had been little relaxtion in its

programme. In all, 62.5 miles had been covered since leaving the works and 16.6 pints of fuel had been used, corresponding 16 30.1 m.p.g. Considering the exceptional operating conditions of the North Downs, this result was praiseworthy.

The next part of the test comprised a mixture of normal and dense traffic work through the suburban areas of Purley, Croydon, Norbury, Streatham and

Brixton to central London. The course followed a former tram route and there were long delays at points where the lines were being uprooted. My desire for dense traffic was satisfied on the .journey along Oxford Street from Marble 'Arch to Regent Street, which occupied 20 mins., and conditions were little better in the City. The van behaved well in all phases of idling and slow running with the general traffic stream. I kept an eye on the radiator temperature, but it did not rise above 176 degrees F. The engine-oil temperature reached a maximum of 128 degrees F. in general running back to the works.

The test occupied 88.8 miles and the average fuel 'return was 30.6 m.p.g., which, in the circumstances, was remarkably economical.

From the fuel returns obtained under varying conditions it is apparent that the Trojan oilerwill reduce fuel bills in any type of service.