Raise Rates for Long-distance Haulage

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THIS 'series was unavoidably interrupted by an article written to conform with the general tenor of the previous issue of The Commercial Motor, in which haulage for farmers was the outstanding feature. Readers will recall that in my May 14 article I set out in Table V the minimum revenue which should be earned by vehicles of 3-ton to 12-ton capacity, engaged upon the haulage of tiles. In calculating those revenues I had taken into consideration the somewhat extended

loading and unloading time, which seems to be unavoidable in the conveyance of loose tiles and which necessitates the employment of at least one man in addition to the driver.

In discussing the matter, I had come to the point of indicating how, in the case of a 7-ton lorry, it would be possible to carry only two loads per day if the lead did not exceed seven or eight miles. As 41. hours are necessary for standing time for each complete journey; only two hours would be left for travelling if two loads are to be carried Within 11 hours. With a longer lead loading would have to be effected overnight in preparation for, a journey next morning andit would be possible to count on an average of only 14 journeys per day.

With 10-ton and 12-ton loads, only the shortest of journeys are• really practicable if More than one is to be run . per day. Take the case of a 10-tonner, for example. With two men, six hours will be needed for loading and unloading, leaving five hours for travelling. That is ample time for a single journey of any reasonable length, but two journeys are out of the question.

I have, however, calculated the figure for a 10-tonner on the basis of a driver and mate being employed. The -revenue which a haulier must make from the operation of a vehicle of this capacity, with driver alone, is 4s. 3d. per hour and OW. per mile run. The addition of a mate means that at least another is. per hour must be earned, making the minimum revenue 5s. 3d. per hour. For the six hours' loading and unloading there must be a revenue of 31s. 6d., and that is the minimum terminal charge.

Each mile lead means two miles of running and up to five miles lead the run occupies eight minutes, the charge for which must be 81d. Add is. 71d. for two miles at 91(1. per mile and the total, 2s. 4d., is the amount which must be earned additional to the above 31s. 6d. for each mile lead. For tw6 miles, therefore,

over the longer distance.,. The time charge. is reduced to and the total kir travelling to 2s. 3d. per mile lead, instead of 2s. 4d.

This is a case of the kind which was mentioned in the first article, when I related the story of a disCtission about tile haulage among three operators who were . experienced in it. It will be recalled how one of them said that he had found that 10-ton loads were profitable, but that-he was rarely able to carry More than one load per day and could find nothing for the vehicle to do in the In the case of a 12-tonner, I have definitely assumed that three men will be employed, as above, and two loaders. That makes the basic figures for time and mileage 6s. 6d. and 100. respectively. The basic terminal charge calculated as above, and allowing for five hours to load and unload, is 32s. 6d. The charge for each mile lead, again calculated as above, is 2s. 9d. per mile lead up to five miles and 2s. 8d. per mile lead beyond that point. Those bases give a figure of 38s. for the revenue for a two-mile lead, rising to a total of 112s 11d, for a 30-mile lead.

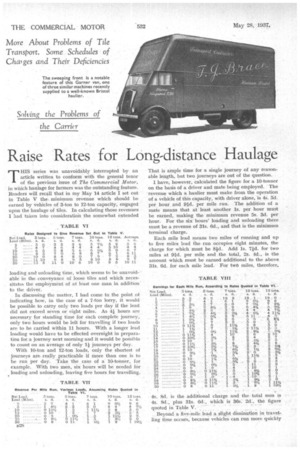

From Table V, following the procedure adopted in the article with which it appeared, I have drawn up Table VI, showing the rates per ton necessary to give that revenue. In a final column I have averaged those rates. It is of interest to compare them with the proposed schedule which I am examining.

The rates which I propose rise fairly evenly from 3s. 5d. for a two,mile lead to 10s. 11d, for a 30-mile lead. In those which are suggested, 4s. 3d. is quoted for a two-mile lead, rising, again more or less regularly, to., 9s. for a 30-mile lead. There is clearly, therefore,

reasonable margin of piofit in the lower category of Rso to

10 10

(Fig. 4.) In this gra revenue per mile i line represents the the broken line

0 5 10

distances, but insufficient in the higher reaches. The proposed rates would, therefore, in. my opinion, be satisfactory only if there were a definite preponderance of short leads and a few long ones.

In considering the possibility of profit from a long lead, one must not overlook the fact that it is in connection with these journeys that loss of time is most prevalent, because of the impossibility, on returning from, say, a load in the afternoon, of tackling another one before the close of the official or legal working day. I am, therefore, strongly of opinion that there should be a tendency to increase rates in respect of long-distance hauls. This recommendation applies with increasing force as the time needed for loading and un loading rises.

In Table VII, figures are given for the revenue per mile run, so assuming that the operator receives the rates quoted in Table VI.

Table VIII is similar in form and purpose to Table IV (published on May 14), in that it shows the re

venue for each mile ran, mile by

mile. It illustrates the tendency for gaps to arise owing to the basic schedule being graduated at five-mile intervals, instead of individual miles.

The foregoing will show that a concession in respect ot rates as the length of lead increases is a short-sighted policy. As I pointed out in my article in the May 7 issue of The Commercial Motor, there is no logical reason for this practice.

The question was further discussed in the issue of May 14, and it was made clear that gaps in a rates schedule inevitably lead to the damaging practice of ratecutting, for which, as I have so often stressed in these columns, there can at no time be justification. S.T.R. B29