Youngsters on the frontline "As an ex-serviceman myself, I'm delighted

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

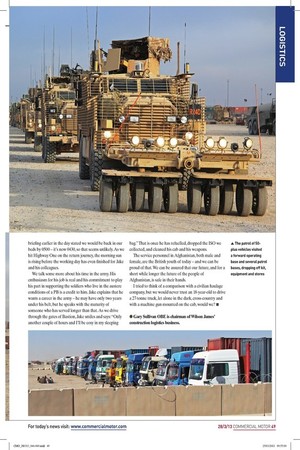

with this feature. So often we're told that young people 'aren't what they used to be'. I hope you'll agree that these young people are the best of the best" Peter Carroll, CM guest editor As I join the Royal. Logistics Corps on a combat logistics patrol (CLP), 18-year-old Jake Smart will be my driver. He has already been in the army for two years. "Pass up your kit," he shouts down from his 27-tonne MAN EPLS (enhanced palletised load system). He hauls up my body armour, helmet and day sack, which probably weigh only a few kilograms less than he does. I climb up into his cab, he shakes my hand and sets about going through a series of checks.

Earlier in the day, I had attended briefings about the task ahead. It was fairly straightforward — take 50-plus vehicles out just before last light, drive through the night visiting a forward operating base (FOB) and several patrol bases (PBs), drop off the kit, equipment and stores on board and, perhaps a little different from my previous visits to Helmand Province, collect non-essential equipment and return it to Camp Bastion. The government has said that UK forces will cease combat in 2014, so the army has started the process of closing PBs and removing all the constituent parts back to Bastion.

As a logistics operation it had no unique features, except that this is Afghanistan; while security is much improved, it still has risks — especially when your driver is barely old enough to vote or buy you a pint. Another feature of a military trucking operation is that the proportion of female drivers is considerably higher, many of them in their early 20s.

The 12 Close Support Logistics Regiment (CSLR) are assigned to be the British Army's haulier for Task Force Helmand. Vehicles in the CLP include not only the EPLS, but also the Oshkosh close support tanker, the MAN Wrecker recovery vehicle along with Mastiff and Ridgeback tactical support vehicles providing force protection. The PBs create the demand pull, but it is 12 CSLR that has to collect the material from Camp Bastion. This can be fresh food, vehicles, spare parts, engineering stores and a variety of products that fall under the heading of military equipment.

Traffic as bad as the M25 As we pull out of Bastion onto Highway One, the traffic is reminiscent of the M25 on a bad day, with many hundreds of Afghan trucks, buses, motorbikes and cars. Jake is unfazed as he manoeuvres his EPLS in and out of the traffic. There appears to be little in the way of rules as colourful vehicles and a moped carrying a family of five weave between the military vehicles.

The conversation flows effortlessly with Jake and, while he recounts tales of his life back in Wyndham, Norfolk, with his friends and family, he tells me he couldn't think of anything better than the job he is doing. "I am helping people, I am doing an exciting job; and I get to drive, which is my passion. I love cars, even when I am at home all I want to do is get out on the road," he says.

As darkness falls, the traffic shows no sign of reducing, that is, until we pull off the highway onto rutted muddy tracks as we head towards our first stop. We pull into the FOB and are directed to the marshalling area. Jake jumps down from his cab and heads off to the Danish coffee shop and Naafi, which is as well known to the RLC as the Watford Gap services are to Eddie Stobart.We have no drops here, so a cup of coffee and a stock up on snacks gives Jake his first and last break. As we pull out, Jake tells me that we have some more cross-country driving to do. He has over a dozen CLPs under his belt now and his calm approach belies his youth. The main highways have numbers but the roads built by the military have names like Elephant, Morpheus and Neptune, and our cross-country drive comes to a welcome end as we hit one of those uniquely named black-topped roads. The CLP comes to a stop and a flurry of activity over the radio tells us that one of the trucks has a mechanical breakdown. Lt Lauren Shepherd is the young troop commander with the responsibility of protecting the CLP. She issues her instructions and the six-wheeled Mastiffs provide the cover while a huge military tow truck, a MAN Wrecker, that accompanies the CLP is brought forward. Jake moves out of his seat and into the cupola to man the general purpose machine gun mounted over the cab, the offending vehicle is hooked up and we are on the move once again in no time.

The PB appears out of the darkness: a modern-day Alamo on the edge of the desert. The gate is barely big enough to fit the vehicles through, but one by one they pass through the entrance in total darkness. As they enter the PB, each co-driver jumps down and leads their truck through the cramped avenues of tents and hardened shelters to protect the inhabitants should they receive indirect fire from mortars. Only a small light held in the hand and pointed downward is used to guide the drivers to the drop-off/pickup points. A choreographed ballet of trucks begins, with ISO containers being dropped and picked up with the minimum of communication, each participant knowing where to be and at what point in the ballet.

A long night's work Jake, with cool professionalism in the cold of an Afghan night, completes his drop-off and pick-up before parking up. But it's not long before we head back to work. The evening doesn't quite go to plan as one piece of kit needs a crane to pick it up and the crane isn't quite up to the job, so we are delayed while a solution is worked out. The briefing earlier in the day stated we would be back in our beds by 0500— it's now 0430, so that seems unlikely. As we hit Highway One on the return journey, the morning sun is rising before the working day has even finished for Jake and his colleagues.

We talk some more about his time in the army. His enthusiasm for his job is real and his commitment to play his part in supporting the soldiers who live in the austere conditions of a PB is a credit to him Jake explains that he wants a career in the army — he may have only two years under his belt, but he speaks with the maturity of someone who has served longer than that. As we drive through the gates of Bastion, Jake smiles and says: "Only another couple of hours and I'll be cosy in my sleeping bag." That is once he has refuelled, dropped the ISO we collected, and cleaned his cab and his weapons.

The service personnel in Afghanistan, both male and female, are the British youth of today — and we can be proud of that. We can be assured that our future, and for a short while longer the future of the people of Afghanistan, is safe in their hands.

I tried to think of a comparison with a civilian haulage company, but we would never trust an 18-year-old to drive a 27-tonne truck, let alone in the dark, cross-country and with a machine gun mounted on the cab, would we? • • Gary Sullivan OBE is chairman of Wilson James' construction logistics business.