THE FINANCIAL problems of the total BL organisation have been

Page 64

Page 65

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

well-documented and argued about for a long while, but the basic fact to emerge from the events of the Seventies was that the commercial vehicle division was starved of investment at a crucial period in its development.

Happily that situation was rectified with a massive injection of capital into Leyland Vehicles with the end result — as far as product is concerned — being the Leyland Roadtrain.

Not all the money went into vehicle development, however. A hefty chunk — 32 million to be exact — went into building and equipping a new factory to build the Roadtrain.

The decision to build the new factory was given the go-ahead by the National Enterprise Board in 1977. The forward planning and design work had already been done so within a month work began on the foundations.

The building progressed according to schedule but, as it would have been asking for trouble to build a brand-new vehicle in a brand-new factory, a pre-production line was set up in what used to be the old Leyland engine test shop.

Thus the teething troubles which inevitably happen during the assembly of pre-production chassis could be ironed out before the new factory came into operation.

The first chassis (a Leopard) went down the line in September last year bang on schedule. The plant is due for completion early next year when the target will be 420 chassis per week built on a two-shift system.

Once again, as a complete programme, the factory is running to schedule. Even now, with more sections of the plant being brought to fully operational standards every month, chassis are coming off the line at the rate of 60 a week.

As with the new Leyland engine test centre, automation and computer control play key roles in the new assembly shop, and this is particularly true of the material flow into the plant.

When the incoming material from an outside supplier arrives at the gates, the information from the relevant delivery notes is fed into the materials management computer which checks that the part is in fact the one asked for and is in the correct quantity.

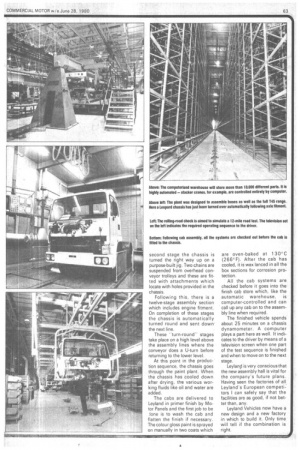

Following the customary quality control checks, the material should then go to the automatic warehouse — -should" because this is one of the areas still to be completed.

As only one assembly track is currently in operation, the production volume is not high enough to cause problems due to the absence of the automatic warehouse. The required storage space for the present level of operation is found under the second track.

The automatic warehouse is scheduled for completion by midsummer and has some impressive statistics. It is 15m high (which is easy enough to remember as it is the maximum length permitted for an artic) and has 20,000 "pigeon holes': for the components. These are divided up into difference sizes; for example, there are 2500 containers for major units, 7100 bins for smaller parts, and so on.

When the automatic warehouse is in operation, the components will be placed in predetermined positions by a stacker crane. If a particular component is required, then it is selected by the automatic stacker crane which is controlled by the computer.

Upside down

As with many competitors' vehicles, Leyland chassis assembly starts upside down for the simple reason that it is easier to fit the springs and axles when the chassis is inverted. This first stage is carried out on a flush floor conveyor using fixed trestles which support the chassis at a convenient working height.

Before moving up to the second stage the chassis is turned the right way up on a purpose-built jig. Two chains are suspended from overhead conveyor trolleys and these are fit ted with attachments which locate with holes provided in the chassis.

Following this, there is a twelve-stage assembly section which includes engine fitment. On completion of these stages the chassis is automatically turned round and sent down' the next line.

These ''turn-round" stages take place on a high level above the assembly lines where the conveyor does a U-turn before returning to the lower level.

At this point in the production sequence, the chassis goes through the paint plant. When. the chassis has cooled down after drying, the various working fluids like oil and water are added.

The cabs are delivered to Leyland in primer finish by Motor Panels arid the first job to be lone is to wash the cab and flatten the finish if necessary. The colour gloss paint is sprayed on manually in two coats which are oven-baked at 130°C (266c F). After the cab has cooled, it is wax lanced in all the box sections for corrosion protection.

All the cab systems are checked before it goes into the finish cab store which, like the automatic warehouse, is computer-controlled and can call up any cab on to the assembly line when required.

The finished vehicle spends about 25 minutes on a chassis dynamometer. A computer plays a part here as well. Itindicates to the driver by means of a television screen when one part of the test sequence is finished and when to move on to the next stage.

Leyland is very conscious that the new assembly hall is vital for the company's future plans. -Having seen the factories of all Leyland's European competitors I can safely say that the facilities are as good, if not bettel. than, any.

Leyland Vehicles now have a new design and a new factory in which to build it. Only time will tell if the combination is right.