Why 'perfectly sound' brakes fail MoT test

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The reason that many operators send their trucks to the test station in good faith, and are surprised when they get a failure notice, is that brake grab and judder may not happen unless the brakes are applied very hard

• Statistics show that brake defects are a more common cause of trucks failing their annual Ministry test than is generally believed. An operator may take his truck in for testing in good faith because the brakes appear perfectly sound on the road, the air pressure gauges show a pressure, and there are no apparent leaks in the system. Yet, quite often, the vehicle will fail to pass its test on the brakes, and the failure usually comes under one of three headings: unequal braking across an axle; low brake efficiency on one axle; or brake grab or brake judder.

It is most unlikely that any of these three failure points is because of a fault in an air operating system, though low efficiency on one wheel could possibly be caused by a sticking or leaking wheel cylinder on an air-over-hydraulic system. It is also possible that low efficiency is caused by oil leaking onto the brake linings, but it is far more likely that the solution to the problem will be found in the mechanical operating part of the brake system between the air chamber and the shoes themselves.

The reason that many operators send their trucks to the test station in good faith, and are surprised when they get a failure notice, is that brake grab and judder in particular, may not happen unless the brakes are applied very hard — a situation which does not, or should not, apply in normal driving. A drop in efficiency on one axle of even a two-axled vehicle, let alone a multi-axled vehicle, is again not usually noticed by the driver until he has to make an emergency brake stop or until the vehicle goes in for its test.

There are two basic reasons, apart from drum troubles, for mechanical problems causing loss of brake efficiency. The first of these reasons is a simple lack of lubrication, and the second is ignorance on the part of fitters who reassemble brake mechanisms after fitting relined brake shoes. Perhaps ignorance is a rather strong word to use here, as fitters who are not familiar with a particular method of assembly can easily make mistakes or misadjustrnents even though they are experienced and conscientious.

Still common on trailers

Dealing with the more simple type of S-cam brakes still quite common on trailers and still plentiful on older trucks, one of the main causes of lost efficiency between the air brake chamber and the brake shoe is lack of lubrication which leads either to seizing up or to worn parts in the linkage.

Working from the air chamber towards the shoe, the first thing to check is the freedom and lack of wear in the brake camshaft and its bearings. It is not usually necessary to use any special grease for lubricating these, though it is advisable not to be so enthusiastic with a pressure grease line that greases past the seal and into the brake drum. Normal chassis grease will soon turn to liquid when the brakes get hot, and will flow past the S-cam to contaminate the linings.

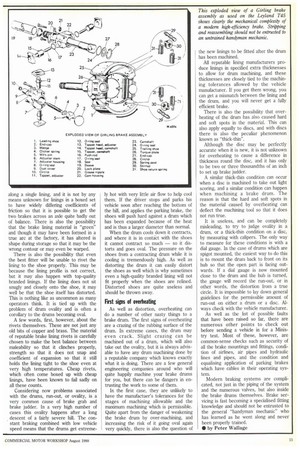

Inside the drum, you should use only a high-temperature grease specified for use in brakes. Not many years ago, such grease was lithium based, and was usually white in colour. Modern technology has altered the base material of the grease and you may now find it in a variety of colours, for example Girling's hightemperature brake grease is now green.

Wherever there is metal-to-metal moving contact, you should use this hightemperature grease. It is not really sufficient just to smear the grease around the outside of the parts which are in contact, as the pressure between these parts is usually so high that the grease has difficulty in finding its way between the surfaces. The brake mechanism should be dismantled and cleaned, and the rubbing surfaces smeared with high-temperature grease before the mechanism is reassembled. Particularly this applies to the anchors of privoted-shoe brakes and to the brakeshoe abutments on the more modern sliding-shoe type.

The wedge and its associated plungers on wedge-operated brakes must be free and well-greased and so must the bellcrank and strut on the type of slidingshoe brake where the bell-crank and strut form a reaction link to makers' assembly, in effect, a twin-leading-shoe system even though there is in actuality, one leading and one trailing shoe. Lack of lubrication of these various points can in extreme cases cause a loss of up to 30% between the effort at the brake chamber and the effort between the lining and the drum.

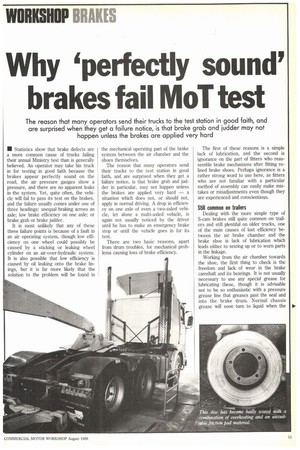

Incorrectly assembled brakes Girling has also found a surprising number of modern brakes which have been incorrectly assembled. If you look at the exploded diagram you will see that a modem wedge brake (the diagram is of the system used on a Leyland 145) comprises a large number of parts, many of which will fit together incorrectly as well as correctly. Though the brake appears to operate, it can be so far below its proper efficiency as to cause a failure on a Ministry test.

Particularly this applies to the assemblies of the camshaft and the wedge adjuster as well as to the attachment points of the pull-off springs. Girling engineers said that there is really no excuse for assembling even a complicated brake wrongly, as the company issues detailed technical manuals and is always willing to send operators a copy of the relevant pages should their fitters be overhauling an unfamiliar brake mechanism. All the other brake manufacturing companies operate similar help-lines, so the golden rule is: "If in doubt, ask" — or as one engineer puts it: "When all else fails, ask for the instructions, and read them."

Automatic slack adjusters on the older S-cam brakes are familiar to almost every fitter and, provided they are kept clean and well lubricated, seldom give much trouble. The more modem type of automatic adjuster which is inside the brake drum is, however, often blamed by fitters for poor operation. This is really an illfounded criticism, as all of the systems in current use work very well provided they are lubricated and assembled properly. Even then, it sometimes happens that the braking system does not seem to work as it should do, and where there are inspection holes in the brake back plates, fitters often find that the brakes do not seem to have adjusted themselves properly.

On sliding-shoe brakes this could be because the shoes are seized and are not sliding as they should, but it is much more likely that the self-adjusting mechanism has not been brought properly into operation after the brakes were assembled. It stands to reason that with even minimum wear in a brake drum there is going to be a slight lip at the edge of the drum where the surface has worn. If the shoes were fully adjusted before the drum was put on, it would be impossible to get this lip over the shoes. So the adjuster has to be slackened off before the drum is replaced.

To bring the shoes into their proper position of adjustment, both with regard to clearance between the lining and the drum, and the proper centralising of the shoes, it is essential to follow the instructions in the vehicle manufacturer's workshop manual. It can vary from make to make, and may not always be just a simple question of making a few hard brake applications.

So much for the mechanical linkage and operation inside the drum. The points dealt with so far cause a surprising number of Ministry test failures, but even if all is well in this respect, there are still a number of other reasons why the brake might fail its test.

One reason is not always appreciated is the use of a cheap brake shoe lining or, on disc brakes, a cheap friction pad. Many operators have the mistaken belief that though the braking material may not be quite up to the high standards of the more expensive lining materials, the only way in which they differ in practice is that the cheaper material will not last as long. This is entirely false, and Girling has investigated a number of "plain white box" imported linings and has found that one of the greatest faults is that they are not consistent in the niaterial.

There can be hard and soft patches along a single lining, and it is not by any means unknown for linings in a boxed set to have widely differing coefficients of friction so that it is possible to get the two brakes across an axle quite badly out of balance. There is also the possibility that the brake lining material is "green" and though it may have been formed in a true arc at the factory, it has altered is shape during storage so that it may be the wrong contour or may even be warped.

There is also the possibility that even the best fitter will be unable to rivet the lining to the shoe properly. This may be because the lining profile is not correct, but it may also happen with top-quality branded linings. If the lining does not sit snugly and closely onto the shoe, it may well be that the shoe itself has distorted. This is nothing like as uncommon as many operators think, It is tied up with the problem of drum ovality and is often a corollary to the drums becoming oval.

A few words, first, however, about the rivets themselves. These are not just any old bits of copper and brass. The material of reputable brake lining rivets is carefully chosen to make the best balance between tnaleability so that it clinches properly, strength so that it does not snap and coefficient of expansion so that it still holds the lining tight to the shoe even at very high temperatures. Cheap rivets, which often come boxed up with cheap linings, have been known to fail sadly on all these counts.

Considering now problems associated with the drums, run-out, or ovality, is a very common cause of brake grab and brake judder. In a very high number of cases this ovality happens after a long descent of a fairly severe hill. The constant braking combined with low vehicle speed means that the drums get extreme ly hot with very little air flow to help cool them. If the driver stops and parks his vehicle soon after reaching the bottom of the hill, and applies the parking brake, the shoes will push hard against a drum which has been expanded because of the heat and is thus a larger diameter than normal.

When the drum cools down it contracts, and where it is in contict with the shoes it cannot contract so much so it distorts and goes oval. The pressure on the shoes from a contracting drum while it is cooling is tremendously high, . As well as distorting the drum it can easily distort the shoes as well which is why sometimes even a high-quality branded lining will not fit properly when the shoes are relined. Distorted shoes are quite useless and should be thrown away.

Fist signs of overheat*

As well as distortion, overheating can do a number of other nasty things to a brake drum. The first signs of overheating are a crazing of the rubbing surface of the drum. In extreme cases, the drum may even crack. Slight crazing can be machined out of a drum, which will also take out the ovality, but it is always advisable to have any drum machining done by a reputable company which knows exactly what it is doing. There are a few general engineering companies around who will quite happily machine your brake drums for you, but there can be dangers in entrusting the work to some of them.

In the first case, they are unlikely to have the manufactuer's tolerances for the stages of machining allowable and the maximum machining which is permissible. Quite apart from the danger of weakening the brake drum by over-machining, and increasing the risk of it going oval again very quickly, there is also the question of the new linings to be fitted after the drum has been machined.

All reputable lining manufacturers produce linings in specified extra thicknesses to allow for drum machining, and these thicknesses are closely tied to the machining tolerances allowed by the vehicle manufacturer. If you get them wrong, you can get a mismatch between the lining and the drum, and you will never get a fully efficient brake.

There is also the possibility that overheating of the drum has also caused hard and soft spots in the material. This can also apply equally to discs, and with discs there is also the peculiar phenomenon known as "thick-thin".

Although the disc may be perfectly accurate when it is new, it is not unknown for overheating to cause a difference in thickness round the disc, and it has only to be two or three thousandths of an inch to set up brake judder.

A similar thick-thin condition can occur when a disc is machined to take out light scoring, and a similar condition can happen when machining a brake drum. The reason is that the hard and soft spots in the material caused by overheating can deflect the machining tool so that it does not run true.

It is useless, and can be completely misleading, to try to judge ovality in a drum, or a thick-thin condition on a disc, by measuring with calipers. The only way to measure for these conditions is with a dial gauge. In the case of drums which are spigot mounted, the easiest way to do this is to mount the drum back to front on its hub so that the open part is facing out wards. If a dial gauge is now mounted close to the drum and the hub is turned, the gauge will record the run-out, or in other words, the distortion from a true circle. It is impossible to lay down general guidelines for the permissible amount of run-out on either a drum or a disc. Always check with the vehicle manufacturer. As well as the list of possible faults that have been raised so far, there are numerous other points to check out before sending a vehicle in for a Ministry test. Most of these, however, are common-sense checks such as security of all the brake mountings and fittings, condition of airlines, air pipes and hydraulic lines and pipes, and the condition and equalising application of parking brakes which have cables in their operating system.

Modern braking systems are complicated, not just in the piping of the system and the numerous valves, but also inside the brake drums themselves. Brake servicing is fast becoming a specialised fitting knowledge and should not be entrusted to the general "handyman mechanic" who has learned as he went along and never been properly trained.

• by Peter Wallage