London's traffic in the shadow of GLC abolition

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

WHEN WE LOOK at the problem of improving traffic flows and the quality of life in London, we soon become aware of another problem: nowhere is directly comparable.

Greater London is so big, the amount of congestion is so great, and the rail service is not that great — a put-off to commuters tempted to leave their cars, company cars particularly, and transfer to BR in the outskirts. The latest cross-roads is the potential abolition of the Greater London Council, which would Balkanise traffic management planning. In the immediate future, the M25 will reduce traffic levels on the North Circular Road; that apart, it seems to be slow speed ahead. Is there a way Out? Let's first look at the background and then discover something of what those in more immediate authority in the capital have to say.

London is the largest city in Europe (with 0.7 per cent of the land area of Great Britain and 23 per cent of the population of England and Wales). It is the capital of a country which, compared with its largest neighbours, France and Germany, is necessarily far more road-freight oriented and is only seventh or eighth in the list of the most prosperous European countries.

While many firms have moved out in recent years, London remains a major UK entrepot, is a leading international centre for finance and commerce, and — like Paris — is a seat of government and a big tourist attraction.

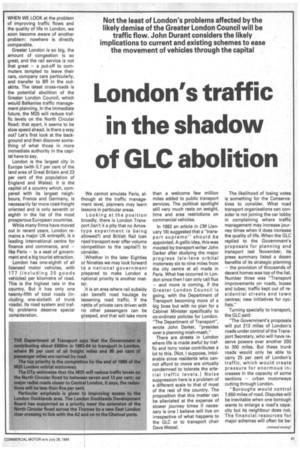

London has one-eighth of all licensed motor vehicles, with 177 (including 20 goods vehicles) per kilometre of road. This is the highest rate in the country. But it has only one twenty-fifth of total roads (including one-sixtieth of trunk roads). Its road system and traffic problems deserve special consideration. We cannot emulate Paris, although at the traffic management level, planners may learn lessons in particular areas.

Looking at the position broadly, there is London Transport (isn't it a pity that no Amostype experiment is being allowed?) and British Rail (can road transport ever offer volume mpetition to the capital?) to nsider.

Whether in the later Eighties o Nineties we may look forward té a national government prepared to make London a national priority is another matter.

It is an area where rail subsidy can benefit road haulage by lessening road traffic. If the nettle of private cars driven with no other passengers can be grasped, and that will take more than a welcome few million miles added to public transport services. The political spotlight still very much rests on weight, time and area restrictions on commercial vehicles.

In 1982 an article in CM (January 16) suggested that a "transport supremo" should be appointed. A gallic idea, this was mooted by transport writer John Darker after studying the major progress (six-lane orbital motorway six to nine miles from the city centre et al) made in Paris. What has occurred in London since then I can only call flux — and more is coming, if the Greater London Council is going, with the Department of Transport becoming more of a big boss but with no plan for a Cabinet Minister specifically to co-ordinate policies for London. "The Department of Transport", wrote John Darker, "presides over a planning mish-mash."

There are streets in London where life is made awful by traffic and lorry noise contributes a lot to this. [Not, I suppose, intolerable since residents who cannot afford to move are virtually condemned to tolerate the arterial traffic levels.] Noise suppression here is a problem of a different scale to that of most of the rest of the country. The proposition that this matter can be alleviated at the expense of slower journey times if necessary is one I believe will live on irrespective of what happens to the GLC or to transport chair Dave Wetzel, The likelihood of losing votes is something for the Conservatives to consider. What road transport organisations can consider is not joining the car lobby in complaining where traffic management may increase journey times when it does increase the quality of life. When the GLC replied to the Government's proposals for planning and transport last November, its press summary listed a dozen benefits of its strategic planning — the provision of thousands of decent homes was top of the list. Number three was "Transport improvements on roads, buses and tubes; traffic kept out of residential streets and town centres; new initiatives for cyclists."

Turning specially to transport, the GLC said: "The Government's proposals will put 213 miles of London's roads under control of the Transport Secretary, who will have reserve powers over another 200 to 300 miles. But these trunk roads would only be able to carry 25 per cent of London's traffic, which would create pressure for enormous increases in the capacity of some sections — urban motorways cutting through London.

"Boroughs would control 7,660 miles of road. Disputes will be inevitable when one borough wants to enlarge a road's capacity but its neighbour does not. The financial resources for major schemes will often be be

yond individual boroughs and there will be inter-borough competition for Government grants.

"The GLC recognises the need for a stable roads policy, but this should be through a Londonwide authority with wide responsibilities and adequate resources that can be accountable to Londoners.

"The Government talks of a 10-to 15-year action programme for trunk roads although it gives no details. But if plans for the North Circular Road are anything to go by that can only mean road building on a major scale."

The GLC report, entitled "From Order to Chaos", pointed out that the Government accepted the need for a Voluntary Joint Committee of boroughs to oversee traffic management such as bus lanes, parking and road safety, yet not one for road planning.

Duplication, it said, is inevitable. Traffic schemes on the 200 to 300 miles of most important borough roads will be vetted by the Transport Department, and boroughs will have to consult with each other and on many occasions the Voluntary Joint Committee.

The GLC said the Government aim to scrap the Greater London Development Plan and instruct the boroughs to produce 33 structure plans cannot produce a simpler, cheaper and more efficient planning system.

Boroughs, it said, respond to local needs, and if they become more involved in London-wide planning this will elevate local interests above the needs of the city as a whole and disperse specialised GLC services, such as in historic buildings.

The Government's hope for voluntary co-operation to overcome these problems, it said, is naive and unworkable.

The GLC dismissed as a sham Government claims that it is giving more power to the boroughs and says that the Environment Secretary will have the whip hand, appointing the Planning Commission and dictating the strategic guidance the boroughs must follow.

As a longstop, said the GLC, he will be able to veto any plan that he chooses. Where action beyond the resources of individual boroughs is needed, the Secretary of State will impose organisations along the lines of the London Docklands Development Corporation. The coordination of transport will be gone.

I went along to see the two most important men, politics apart, in planning and adminis tering transport in London: the GLC's David Bayliss, chief planner (transportation Department of Planning and Transportation, at County Hall, and Deputy Assistant Commissioner Colin Sutton, at Scotland Yard.

David Bayliss, I suppose, must have thought: "Here's another one come to quiz me about Talgarth Road" — for the benefit of those who live far from Westi London that's the notorious spot where an imposed right turn has been adding to traffic delays, but to go into detail about that experiment is outside my purpose

here of a general look at London traffic.

He explained that the GLC's transport department has four main branches: transportation planning; traffic; construction; and development planning. Traffic, for instance, deals with such things as signals and signs for bus lanes. An important area is the traffic control systems, involving second-by-second observation via computers for the green phase operation of traffic lights in the West End. There are plans to extend this, he said, to the rest of Central London, with corridors to Croydon and Edgware.

The 200th bus lane was brought in in May, he pointed out.

He attaches great importance to the Department's black-spot analysis; such schemes as the "Motorcycle keep your lights on" campaign had emerged from this and much low-cost remedial road work had been put in hand as a result which must have saved thousands of accidents.

"My branch," he said, "is responsible for policy generally, and we also have to put programmes through the political and administrative machinery to the point where engineers can take them over."

Besides such proposals as the London-wide night-time lorry ban, traffic management also takes in the current look at an East-West corridor through Hackney where substantial roadbuilding is not a reasonable proposition.

On trunk road improvement, he said, the GLC believes some of those of the Department of transport are too gross in scale and county council officers had spent a lot of time putting forward more limited schemes, but with what success remains to be seen.

Transport plainly needs a lot of personnel, but Mr Bailey took me up when I asked whether he could foresee any end to escalation. My underlying assumption here was wrong. The Department now employs 930 people, but back in 1969 the figure was 1,350. "We were staffed up then for a major roadbuilding programme, but we aren't any more. However, part of the reason for the reduction is im

proved efficiency."

As I approached county hall at 10.15am, I noticed once again that the continuous stream of traffic seemed to be 90 per cent driver-only private cars. If one were to ask the proverbial man on the Clapham omnibus for his explanation of who these people are, I suppose he would be likely to answer "commuters and commercial travellers". Finding out who they are, why they are driving and whether they could be weaned to public transport (as someone who uses the Tubes nearly every day I wonder how many more they can take*) seems to me beyond a gargantuan task; no survey can stop the traffic in order to ask.

But Mr Bailey is not so pessimistic. "Oh, there are lots of ways," he said, "including surveys at car parks and that sort of thing. But we do save a lot of money if we use National Census time. We need 400 people for home interview samples, so last time we brought in a private firm, and we hope this year to publish a major report. Now that the GLC faces the threat of abolition we want to show the world."

Since 1971 computers have been used in such tasks at county hall, he said. Surveys are used as a sort of test bench, and monitoring, as an ongoing exercise of finger on the pulse, started in the early 1960s. However, last May the forecast made when London Transport fares were to be reduced had not proved very accurate (demand was underestimated).

Mr Bailey referred to the strides being made in harnessing technology towards effective traffic management in Singapore and Hong Kong and when I went to see Mr Sutton his references ranged even farther afield. "Our problem is that we have 20th Century traffic on 16th and 17th Century road systems; there is an annual increase in road traffic but it is a non-starter to bulldoze and redesign, as they did in Seoul in South Korea.

"The M25 may have some impact, but quite what nobody knows; patterns take time to become established. We'll see only after the complete orbital road is completed. Any lorry bans will have some impact and some commercial companies may move out of London. Our problem is dealing with things as they are; there is vast commuter traffic and people have a right to bring their cars in."

In the traffic management field there are some problems, he said; the police are consulted at all levels and by and large the solutions work. But, he added, according to the GLC 300,000 vehicles are parked illegally every day, and with a force of 27,000 the Metropolitan Police are hard pushed to make an impact.

In his view the attitude of drivers needs to change. With better behaviour and skill from drivers many problems can at least be reduced. Ninety per cent of drivers are law abiding, but it is the selfish ones who cause prob

lems for others.

The Assistant Chief Commissioner made two specific points here. One; better behaviour at junctions — "drivers don't go barging through in similar situations as pedestrians"—would aid traffic flow tremendously ("we don't want great yellow box grids everywhere"); two: we need a better driving test, including night-time and motorway driving —"the Highway Code is a 1930's production and it's a different world out on the streets.

"We are under-resourced on the police and our priorities are street crime and burglary," he pointed out.

I asked him about the affect of bus-only lanes. "They're useful if they cover the whole of the route but a length of a quarter or a half-mile is no real advantage, while they narrow the roads for others." And traffic wardens? "The 1,800 traffic wardens are confined largely to traffic control and illegal parking, and it's mostly day-time working."

Mr Sutton's idea of a radical solution would be the provision of car parking facilities on the fringes of London with free transport, or, say a 30p charge, on park and ride lines into the capital ("no enforcement you can't stop cars coming in") and then perhaps the police could really deal with the illegal parkers whose numbers would be greatly reduced. Lorry bans are just one more task add them to demos making more manpower demands on the modern Metropolitan Police.

"There are all sorts of solutions that require investment, such as the conversion of defunct railway lines."

As he pointed out, there are vast improvement in traffic flows when the schools are on holiday and mums are off the roads.

"The public will put up with all sorts of inconvenience to stick with their cars," he added. The provision of parking and transport facilities near the radial routes in the Greater London Area, it seems to me, is one of the most likely developments, but naturally transport cannot be run for motorists at below the fares charged to the general public the overwhelming majority of the public who do not own cars and are from onecar families. The other day, for instance, a mere four-station journey near the end of the Piccadilly Line cost me 80 pence single fare. So this idea is inextricably tied up with the provision of very cheap fares.

For the immediate future it is good news that we may be getting some better road signs electronic noticeboards that have been developed in France. "This is being looked at now," he said, "not necessarily as more street furniture but possibly on high-sided vehicles moved into position."

Better road signs and more information on the radio could help to alleviate frustration by drivers and encourage better driving, which would result in more safety, he believes.

*In real terms, said the GLC, the total level of transport expenditure accepted by the Government has dropped since 1975-76 by almost 20 per cent to £461.8m in 1983-84. As a result London Transport's original 10year plan to modernise the Underground (the system is mostly more than 70 years old) has had to be curtailed. However, from the White Paper The Government's Expenditure Plans 198384 to 1985-86, the GLC reckoned there will be an increase of 5.3 per cent in cash terms in the level of local transport expenditure in 1984-85 and an increase of 4.2 per cent in 1985-86.