The news must get through

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

How John Menzies of Edinburgh gear their transport system to meet all eventualities in the wholesale distribution of news papers and periodicals

PICTURES BY DICK ROSS

TT is odd how many of us unthinkingly demand as of right particular standards of service. The regularity with which our morning paper appears on the breakfast table or bookstall is a typical example. Here we all expect, if not demand, perfection despite a lowering of standards elsewhere. Indeed the occasion when the morning paper is not available is so rare that its nonappearance assumes the proportion of a minor disaster. In contrast, the very regularity of its appearance belies the organization that makes such a high standard of service possible.

Yet by the time the printing presses have stopped, prodigious efforts have already gone into daily reproducing the world's news for the price of a few pence. But all that effort could be lost if the wholesale newsagent failed to complete on time his complex task of distribution in the early hours before even the retail newsagent— himself an early riser—opens his shop.

The John Menzies group provides an excellent example of just how complex and exacting the work of wholesale newspaper distribution can be and how vital is the role of road transport in the exercise. This was demonstrated to me when I recently visited the group's transport organization in Edinburgh. I also saw how they handled the additional task of redistributing more than 1,300 different periodicals and magazines to 550 newsagents.

The original bookshop was opened in Princes Street, Edinburgh, by John Menzies in 1833. Business grew and 60 retail shops have now been established throughout Scotland with bookstalls in 128 railway stations, bus stations and airports in Scotland all carrying the name of John Menzies and Co. Ltd. There are also 30 wholesale depots, including Menzies House, Glasgow. and the company headquarters at Rose Street, Edinburgh.

In 1959 there was a raid over the border when John Menzies bought a similar business in England—namely, Wyman and Sons Ltd., later to become Wyman Marshall Ltd. Further expansion followed when in 1961 Charles Henry Pickles of Leeds was acquired, whilst the addition of C. Porter and Co. Ltd., of Belfast and Londonderry, has given coverage in Northern Ireland. In all, the parent company—John Menzies (Holdings) Ltd.—now employs 4,500 to staff more than 500 shops and bookstalls and 100 depots. As such it constitutes one of the largest wholesale and retail newsagents in Great Britain.

The group fleet consists of 466 vans and cars, with the C licences being in the name of the holding company. Of these, 90 vans carry the livery of "John Menzies" and are controlled from the headquarters of the transport department located at Roseburn Street, Edinburgh. So it was there, at the well-appointed offices and garage, that I discussed the distribution problems of John Menzies with their transport manager, Mr. A. G. Hunter.

Dealing first with the composition of the commercial fleet, all 90 vehicles are fitted with van bodies with carrying capacities mainly in the range of 6 cwt. to 4 tons, plus two 7-tonners. But the majority (75) are in the lower capacity range of 2 tons or less. Already predominantly standardized on vehicles of BMC manufacture, Mr. Hunter told me that he expects to achieve 100 per cent standardization early this year.

All vehicles of 20 cwt. and over have the company livery consisting of dark green with the name "John Menzies" painted in green letters on the reverse side of a Perspex signboard which is itself coloured white. The separate nameboards facilitate interchange of vehicles between the various fleets. This group also has special bodies made locally by Commercial Coachcraft Co. which is virtually adjacent to John Menzies' transport department. They are constructed to allow three-way loading by virtue of a roller shutter at the rear and two staggered sliding side doors. The predominant colour is dark green with the cab, skirt and entire rear painted black.

The interior of these specially constructed van bodies is painted aluminium to give better visibility inside coupled with a moulded one-piece roof of transulcent glass fibre. The body panels are colour-impregnated glass fibre with a floor of plywood. Mr. Hunter was critical of the normal housing of many spare wheels. This was often under the rear of the body and if an extension were added the spare wheel became almost inaccessible. Deep skirting-boards, trapdoors and the accumulative effect of water and dirt thrown up on the road all contributed to difficulties when the spare wheel was urgently required, as could occur in an early morning newspaper run. To avoid this trouble the company was experimenting with fitting the spare wheel housing at the side of its 2-, 3and 4-tonners. A major complaint is the continuing lack of accessibility for maintenance purposes in vehicle design.

The front name-board is of similar construction to the sideboard and in addition is lit from the interior by two Easco 20W fluorescent lamps. This arrangement serves the double purpose of both headboard and interior illumination.

Supplementing the three-way loading on the larger vans is the provision of boards and slots at appropriate intervals to allow three separate compartments to be readily made up when required, with each compartment having its own access door. This arrangement facilitates the correct distribution of newspapers and periodicals when multiple deliveries are being made in the early hours to a tight schedule.

All four corners of the van bodies are constructed of rubber from top to bottom with no rigid backing. In addition, white rubber fenders are fitted at waist height horizontally all round the body.

Apart from the 6 cwt. vans all vehicles are fitted with diesel engines and the replacement policy is based on a vehicle life of 5 to 7 years according to usage.

The average length of service of drivers is around eight years, with some having been with the company for 30 years. About 75 per cent of the drivers start work at 4 a.m. and after completion of the all-important early morning run they are employed on additional runs with periodicals.

Vital necessity

A special feature of Scottish newspaper distribution is that the differing national holidays on each side of the Border result in every weekday (including national holidays) having to be worked, with correspondingly greater demands on vehicle availability.

Because of the vital necessity of getting the daily papers to the retailer—come what may—particular attention is paid to selection of drivers, including a thorough test in which "noncommercial" types are weeded out. Additionally, because of the early hour at which the driver will be making the delivery—with no passers by from whom to obtain advice—it is imperative that he should know not only the location of the customer but literally the particular doorway where the bundle of papers should be left long before anyone else is up and around.

Incidentally, if a newsagent does not happen to have a covered doorway to his shop it could even be that his bundle of papers may be left at a neighbouring shop with better provisions in this respect. With perhaps 30-40 deliveries to be completed within the short time available before the newsagent opens his shop, the driver must know his round like the proverbial back of his hand. To acquire such detailed knowledge of local geography it is necessary for new drivers to understudy old hands on one particular delivery round and when proficient complete their education by taking over on their own. Should this prove satisfactory they then learn other delivery rounds. But although there are upwards of 30 such rounds based in Edinburgh alone, a driver does not normally learn more than five of these because of the complexity of their make-up.

Commercial vehicles are based at 19 wholesale branches and are serviced by local retail garages to the specified requirements of John Menzies. Advantage has been taken of the extended servicing period now recommended by the manufacturer, and routine servicing is now undertaken every 2,000 miles with more comprehensive maintenance at 4,000-, 8,000and 16,000-mile intervals.

Servicing undertaken at public garages is authorized by the Edinburgh office, whilst the vehicles are brought back to Edinburgh for the major servicing at 8,000and 16,000-mile intervals. Because of the continuous delivery service which must be provided from Monday to Saturday, difficulties can arise in making vehicles available for maintenance. But to some extent the early hours necessitated by newspaper distribution do result in vehicles being available on their equally early return for maintenance during normal working hours.

To the layman the traffic handled by John Menzies is simply newspapers and periodicals. But to the Scottish wholesaler this is broken down into four groups—national dailies (printed in Glasgow and Edinburgh), English dailies (printed in London and Manchester), periodicals (both weekly and fortnightly) and magazines published monthly or bi-monthly. All of these have their own delivery times and associated routine of distribution.

For example, some of the London dailies bound for Scotland leave Heathrow Airport at 11.40 p.m. and are due to arrive at Edinburgh airport at 1 a.m. Awaiting its arrival will be a 30 cwt. van of the John Menzies fleet with special authority to go on the apron to the plane once it is landed.

Having brought the newspapers to the terminal building, some are left there for the bulk vehicles to collect after previously loading the Edinburgh dailies for distribution to other wholesale branches. The van itself returns with its complement of London's dailies to the Rose Street headquarters for sorting prior to redistribution to news agents.

But if the plane does not land at Edinburgh and for one reason or another is diverted to Glasgow or Prestwick, Scottish readers will still expect to get their choice of morning papers.

To ensure the news still gets through John Menzies has alternative working arrangements ready to put into operation should just such an eventuality arise, with the drivers, branch managers and all concerned already issued with detailed substitute instructions. Time is too short to report back to base for those same instructions. Moreover, advance information as to a diversion cannot be obtained from the airport authorities because the pilot alone makes the decision whether or not to land.

Yet despite such diversions involving an additional 100to 150mile round trip coupled with the rigours of a Scottish winter, newspaper distribution is still maintained. So much for the political gibe that C-licensed operators do not really understand transport!

However, Mr. Hunter told me, a trend in the reverse direction is the fluctuation in size of some dailies and periodicals with a resulting reduction in copies per bundle and corresponding increase in bundles per issue. This, in turn, if the trend persists, could compel a rescheduling of vehicles to journeys. Thus 2-tonners will have to be replaced by 3-tonners and so on. and next year it is envisaged that the 4-tonners due for replacement will, in fact, be superseded by 5-tonners. In addition to this increase in size of some publications, more periodicals are being sold, so adding to the overall load.

Rail closures Rail closures in Scotland, particularly in the past 18 months, have resulted in John Menzies having to provide additional vehicles to maintain the distribution of papers and periodicals in the areas involved. Where such a closure occurs Mr. Hunter checks the proposed run against the provisional timetable it is intended to put into operation.

In the event, as he pointed out, the area concerned invariably finishes up with a better service than before because even in its heyday the railways did not deliver to the newsagent's door. Invariably it was left to the newsagent to devise his own means of getting his supplies from the railway station and in such sparsely populated areas as exist in Scotland, these could be considerable distances away from the towns and villages the railways served.

For the future Mr. Hunter said that trends in the trade were towards automated warehouses which would include conveyor belts, automatic bundle tiers and automatic sorters.

A peculiarity of this trade is that no signatures are obtained on delivery. Drivers load their own vehicles and subsequently effect delivery all on trust. This is yet another reason why the initial driver selection must be thorough. An average van-load would include bundles of dailies, the appropriate periodicals for that particular day, plus bundles of sundries such as books and stationery.

The spare parts position is much in the news lately and Mr. Hunter's experience is pertinent to current comment. Because of the high standard of maintenance demanded of vehicles engaged in distrubuting such perishable traffic, John Menzies built up considerable stocks of spare parts around 1955. Then as spares became more readily available from local suppliers the group's own stocks were allowed to run down. But because the shortage of spare parts is now reverting to the level which applied in the immediate post-war years, stocks have to be built up again because, as Mr. Hunter put it: "In our trade we must have the spares to do a repair job immediately."

With each delivery run being so specialized and largely selfcontained, I asked Mr. Hunter what savings—transportwisethere were to be obtained by mergers with companies in England. Whilst he agreed that there was little opportunity for inter-working at operational level on final distribution, there were undoubted benefits to be obtained through centralized buying, standardization, and the respect which any supplier inevitably has for a large customer.

Under the group transport manager, Mr. R. A. Romanis, all licensing is centralized at Edinburgh, along with insurance, accounts and vehicle buying. Fleets, however, are operated locally by the company transport managers. Thus Northern Ireland is controlled from Belfast with a workshop in Londonderry in addition to one at Belfast. The Yorkshire fleet is controlled from a new workshop and garage in Leeds and the Wyman Marshall fleet from a workshop in Southend.

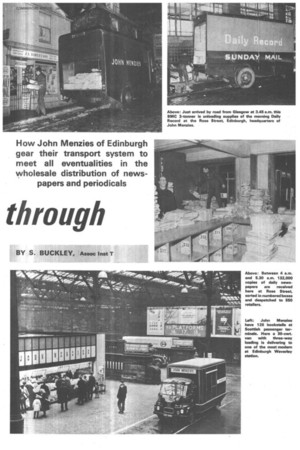

Finally, I paid a visit to the Rose Street headquarters of John Menzies where each week-day morning between 4 a.m. and 5.30 a.m. they receive, sort and repack 132,000 copies of daily newspapers, comprising 25 different titles. In addition 550 weekly and 600 monthly publications are handled, whilst the outgoing bundles are destined for over 550 retailers.

Indicative of the tight schedule to which they work, the man in charge of this hive of early morning activity, Mr. John B. Hill, the news manager, showed me one example of a typical delivery schedule. As already mentioned, newspapers and periodicals are received overnight from a variety of sources and means of conveyance, with the major sorting and repackaging being undertaken between 4 and 5.30 a.m.

Actually the example journey chosen—the East Lothian run— is timed to leave at 4.50 a.m. The driver makes his first delivery at Haddington at 5.50 a.m. and has completed all his deliveries by the time he arrives at North Berwick at 7 a.m. On return to Edinburgh he will have done an 85-mile round trip and will then be available for further trips with periodicals.

Without the availability of the flexible and reliable road transport organization John Menzies operates, such a level of timescheduling could not be contemplated, let alone maintained. In essence the exercise is one of distributing a "commodity" so perishable that if it is not available in every hamlet within eight hours or so of its being "made" it is likely to be unsaleable and finish up literally as pulp. The rarity with which we fail to get our morning paper is the measure of success with which this high standard of distribution is maintained.