Leyland Daf -the odc couple?

Page 12

Page 13

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• As recently as 18 months ago, Daf chairman Aart van der Padt made it clear that he saw no future in his company owning overseas assembly plants building Dafs. What he envisaged was a series of related plants, largely owned within their own countries, building Daf-designed products suited to each market, and trading components with each other. The last thing Daf wanted was any more assembly capacity of its own. So what changed?

Basically, says van der Padt, "we didn't know that in expansion we would touch on this opportunity" to gain, at a stroke, Leyland's share of the British market. What is clear is that with the exception of the Roadrunner and Sherpa models, Daf was not interested in Leyland's model line-up. Van der Padt still quotes economist Peter Drucker in setting out his basic philosophy: "It's better to own a market than a mill." He goes on to say: "The UK market and Leyland's share of it, that's the interest," but points out there was one major problem in acquiring that share: Daf could not add 10,000 units to its existing assembly capacity, so to take on Leyland's home market share, it had to take on Leyland's main assembly plant.

The Freight Rover operation needed no such conceptual somersaults. Daf has not made a light van since — in its original guise as van Doorne's Autombilfabriek — it built a commercial version of the unlamented Daf 33 belt-driven car. The car-building side of the original Daf company is now controlled by Volvo, with a strong Renault presence.

MARKET ENTRY

The Freight Rover operation was, therefore, easy to justify. It makes money in its own right, and offers Daf an entry into a market where it had neither products nor expertise. According to George Simpson (Leyland Trucks' managing director), output of the existing Sherpa can easily be doubled from its present 20,000 a year by adding a second shift at the Common Lane factory. Work has been proceeding for some time on a replacement for the present Sherpa: development of the new vehicle, which apparently has front-wheel drive, will be accelerated.

While Daf could happily make such decisions, Leyland did not have that luxury. Simpson says that Leyland's fortunes had recovered a little since last year, and points out that the widely-quoted figure of £1.5 million lost each week was the 1986 figure. Although they were smaller the losses were continuing, and since his move into the managing director's chair in October, Simpson had already started planning further cuts in plant and work force. He will not specify just how savage those planned cuts would have been, but confirms that unless Daf (or Paccar) had come along, much higher losses than have now been announced would have been needed to keep Leyland going "as a stand-alone unit".

What is also clear is that even those bigger job cuts and plant closures would have been short-term solutions at best. Leyland was not generating sufficient money to pay for the next generation of heavy vehicles. Given that the first of the respected 145 range — the Roadtrain — has been in production for more than six years, and was signed off as a design well before 1980, there was going to be a critical demand for a replace

client within a couple of years, and that did not exist. So without a rescue by an organisation big enough to produce a state-of-the-art replacement for the 1'45 range, Leyland would have been unable to protect its major remaining asset — its market share — for long. It was that simple fact which made the Daf deal inevitable: there was no other company both willing to take Leyland on and able to provide the ready-made replacement for an ageing range.

SIMILARITIES

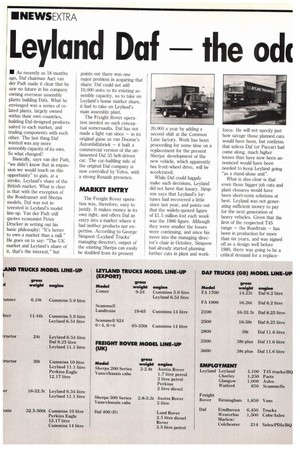

The two organisations are surprisingly similar in size: Daf employs a total of 9,300 people around the world; Leyland and Freight Rover employ a total of 8,850. Daf has two major factories: a components plant at Westerlo in Belgium and assembly plant at Eindhoven in Holland. Leyland has two assembly plants (Leyland, and Scammell at Watford) and one major satellite components plant at Scotstoun in Glasgow, while Freight Rover has one plant in Birmingham.

Last year Daf sold some 16,000 trucks above 3.5 tonnes GVW in Western Europe: Leyland sold 9,600. Daf made a profit of 210.4 million, where Leyland lost 2102 million. Freight Rover is currently geared to produce some 20,000 vans a year on singleshift operation of its Common Lane plant. Its financial performance has never been isolated from that of its parent, the Land Rover Group, which made a half-year profit in 1986 of £8.7 million.

At the moment (leaving aside Sherpas and the Roadrunner-based 600, 800 and 1000 models) Daf is largely self-sufficient, building its own cabs, chassis and engines and buying in gearboxes. Leyland's cabs are built by Motor Panels in Coventry, and with the exception of the 400 series and 1'L11 engines, it buys its engines from Cummins, Perkins or Daf. Its gearboxes come from Eaton, ZF and Spicer, but axles are largely in-house, from the old Albion plant at Scotstoun where there has been a major investment in the past couple of years and whence a new axle range is about to appear.

Freight Rover builds its own chassis and bodies, but relies heavily on the parts bins of its erstwhile sister companies for mechanical components. Its engines are from Austin Rover (1.7 and two-litre '0' Series petrol and the Perkinsdeveloped MDI two-litre diesel) and Land Rover (2.5 litre diesel and 3.5-litre vee-eight petrol) while its gearboxes come from Land Rover and drive axles are derived from those of the Austin Westminster saloon of the 1950s.

Daf is preparing to launch a new cab which has been developed by a joint-venture company (Cabtech) in which Daf and Pegaso are partners. This cab is also scheduled to replace the current range of cabs built for Pegaso subsidiary Seddon Atkinson by Motor Panels. The Leyland Daf deal raises the intriguing possibility of either Daf building Leyland/Daf and Seddon Atkinson cabs at Westerlo, or cabs for both British manufacturers being assembled here, perhaps by Motor Panels.

Leyland's parts operations are based at its vast purposebuilt warehouse at Chorley in Lancashire, which also handles parts for the recently-privatised Leyland Bus organisation. Did's parts are handled through its Marlow, Buckinghamshire, headquarters, but are scheduled to be transferred with the headquarters to a new head office/warehouse at Thame in Oxfordshire. How much of that will now happen must be open to question. Freight Rover parts are presently handled by the Land Rover Group, but these will be transferred to Chorley.

MPs' RESPONSE It was clear from the Commons exchanges after the Industry Secretary's announcement of the Leyland!Daf deal that the Government has got away with it politically, in sharp contrast to the fiasco last year when there were moves to sell Leyland Trucks and land Rover, to GM.

Ironically, many of the Government's fiercest critics during the abortive Leyland/GM talks were only too pleased to see the Leyland Daf merger go through, leaving other Rover Group companies in their own constituencies relatively untouched.

Ann Winterton, MP for Congleton, said the decision would "strike dismay" in the hearts of the manufacturing sector and components industry. Major Leyland customers much preferred the Paccar option and the decision to merge the company with Daf could help Foden and ERF.

Industry Secretary Paul Channon claimed that the joint venture would lead to Leyland producing a larger number of trucks.

Opposition MPs were uniformly hostile to the proposals. Coventry North-East MP George Park said that it would have made more sense for the merger to have taken place in the reverse direction, given that Leyland Vehicles were the market leaders. Channon retorted that that option, given Leyland Trucks' losses, was simply not on offer. "I am convinced that we shall see a much stronger commercial vehicle industry.